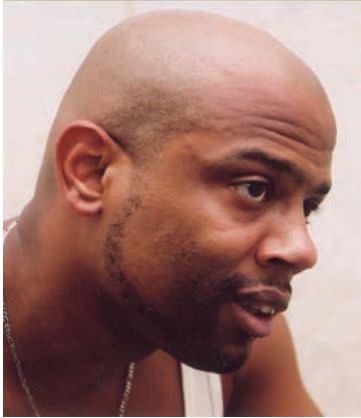

Oklahoma Executes Man Who Struggled With Severe Mental Illness

Oklahoma executed 46-year-old Donald Grant on Thursday, killing a man who struggled with severe mental illness and brain damage. Grant is the third person killed by the state in recent months amid a lawsuit over whether Oklahoma’s lethal injection protocol violates constitutional protections against cruel and unusual punishment.

Grant was killed with a lethal injection of midazolam, vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride — the same combination of drugs used in the high-profile botched execution of Clayton Lockett in 2014. After a years-long pause on executions, Oklahoma officials used the same drug protocol last October to kill John Marion Grant (no relation), who vomited and gasped for air as he died.

Donald Grant feared his execution would be botched, he told KFOR’s Ali Meyer over the phone before he was killed. Media witnesses did not describe any signs of visible suffering, although the state’s lethal injection contains a paralytic that can mask signs of pain. Associated Press reporter Sean Murphy, who witnessed the execution, reported that Grant’s last words included, “Yo, God, I got this.”

“There is no principled basis for allowing Oklahoma to move forward with any executions right now,” Jennifer Moreno, one of the federal defenders representing the plaintiffs in the lethal injection litigation said in a statement. “The problematic execution of John Grant, as well as the mistakes the state made in the executions of [Lockett] and Charles Warner in 2014 and 2015, show that the State’s midazolam-based protocol creates too much risk of pain and suffering. A trial is scheduled at the end of February where these issues will be fully litigated on the merits. A short pause would be more prudent.”

Grant was executed as punishment for killing Brenda McElyea and Suzette Smith, employees at a La Quinta Inn, during a 2001 robbery to get money to bail his girlfriend out of jail. McElyea’s sister, Shirl Pilcher, said in a statement that although Grant’s execution “does not bring Brenda back, it allows us all to finally move forward knowing justice was served.”

An Abusive Childhood

Like many of the people who are sentenced to die in the U.S., Grant grew up in poverty and endured extreme abuse. His mother drank heavily while pregnant, and complications during birth “severely impaired his brain development and left him with lifelong disabilities,” Carolyn Crawford, a doctor who specializes in perinatal medicine, concluded after reviewing Grant’s brain scans and his mother’s pregnancy and delivery records.

Grant’s father also struggled with alcoholism and “had a violent temper when he was drunk,” Grant’s brother Shawn Robinson said in a 2010 statement. “One time he picked Donald up by the foot and dropped him headfirst on a marble floor when Donald was very young,” Robinson said. Several times a week, Grant’s father would slam his head into a metal pole in the basement of their apartment, his brother testified at trial. Grant’s mother beat him, too, using curtain rods, extension cords and high-heeled shoes.

When Grant was about 6, his parents split up. He, his mother and his four siblings were homeless. They eventually moved into Grant’s grandmother’s apartment in a Brooklyn housing project. As many as 26 people lived in the three-bedroom apartment at a time. Several of the children living in the apartment were sexually abused by Grant’s uncles, according to Grant’s sister Juzzell Robinson.

Most of the adults in the apartment, including Grant’s mother, struggled with drug addiction. Grant stole food to eat and got a job packing groceries. Sometimes, while Grant and his siblings slept at night, their mother and uncles would steal money out of their pockets to buy drugs, Shawn Robinson said.

Grant’s mother eventually moved him and his siblings out of his grandmother’s home, and they shuffled between New York City’s shelters and welfare hotels — at least 15 to 20 different ones, Juzzell Robinson estimated. When Grant was 12, his grandmother reported his mother to the Bureau of Child Welfare. Grant and one of his brothers were placed in a group home, separated from the rest of their family.

Grant was placed in special education classes until he stopped going to school in the ninth grade. When he was about 14, his mother came up with a plan to “kidnap” her kids from New York’s protective services and move them to North Carolina, Grant’s lawyers wrote in his clemency application. His mother was still addicted to crack, and they still lacked stable housing and money for food and clothes. In the clemency packet, Grant’s lawyers quote several family members who recall Grant exhibiting bizarre and abrupt behavioral changes as a child.

Soon after the move, Grant was found delinquent in juvenile court and found to have committed felony breaking and entering, felony larceny and second-degree burglary. He was placed in a juvenile training school and was assessed as having “borderline intellectual functioning.” Throughout his teens, he continued getting in trouble for theft.

Grant’s mother’s husband, Ronald Williams, believed Grant “had problems with his mind,” he said in a 2007 statement. “Even when Donald was older and he was doing good, he would still snap. He would make these faces, and you could tell he wasn’t right,” Williams said. “I thought the boy was suicidal. He isolated himself. I used to hear him talking like he was talking to someone else, then I would go in the room and see no one was there but him.”

After the 2001 double homicide, Grant’s trial proceedings were stalled for four years because he was incompetent to stand trial, according to his clemency application. Several doctors found that Grant showed symptoms of psychosis. At least two doctors, including one hired by the state, diagnosed him with schizophrenia.

When Grant finally testified in court in 2005, his statements were rambling and nonsensical. Questioned about a potential conflict of interest involving his lawyer, Grant responded, “My theory plays my whole background. That’s for one. My way of life is I’m going to leave this planet earth. That’s my theory. My theory I stand on it and it don’t have to have nothing to do with this. My theory is my theory, you see what I’m saying.”

Despite evidence of untreated mental illness, Grant was convicted and sentenced to death in 2005. Several groups, including the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the American Bar Association (ABA), have called for a prohibition on capital punishment for those with serious mental illness at the time of the crime.

The Supreme Court has held that it is unconstitutional to execute people under the age of 18 and people who have intellectual disabilities.

“The rationale behind these decisions was simple: individuals whose brains were either not fully developed or impaired lack the culpability necessary to be executed,” NAMI says on its website, noting that the Supreme Court specifically identified several factors that are also “applicable to the active symptoms of [serious mental illness], such as the delusions and hallucinations characteristic of psychosis.”

Execution Test Subjects

Grant is one of dozens of people on death row who are plaintiffs in a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of Oklahoma’s three-drug execution protocol. During a May 2020 hearing, U.S. District Judge Stephen Friot stated that he had received assurances from the state’s then-attorney general, Mike Hunter, that the state would not seek execution dates until the litigation was completed.

According to the Supreme Court, for lethal injection challenges to succeed, individuals have to not only show that the execution method is unconstitutional but also offer an alternative. In a court filing all of the plaintiffs signed on to, lawyers offered four alternative methods, but Friot instructed each plaintiff to indicate their specific preference. Six of the plaintiffs declined to do so, mostly citing religious or ethical objections to participating in their own killing.

Last year, Friot ruled that the case could proceed to trial — but he dismissed the six plaintiffs who failed to indicate their preferred method of death. In a footnote, Friot appeared to invite the state to kill these individuals so that their executions could provide evidence as to whether Oklahoma’s execution method does, indeed, constitute cruel and unusual punishment.

“Because ... six of the plaintiffs in the case at bar have declined to proffer an alternative method of execution, there may well be a track record ... of the new Oklahoma protocol by the time this case is called for trial as to the other twenty-six plaintiffs,” the judge wrote.

The state took Friot’s suggestion and quickly scheduled execution dates for those six men — including Donald Grant — plus a seventh man who was never party to the lawsuit. The six men were later reinstated to the lawsuit, but the state has continued to push forward with executions.

In October, the first of the group to be executed, John Grant, appeared to suffer while he was dying.

“I’d never seen anybody gasp for air like that in my life,” Julie Gardner, an investigator with the federal public defender’s office in the Western District of Oklahoma, who observed the execution, said in a recent hearing. “I’d never seen anybody vomit as much as he vomited except maybe on a TV show or some horror show,” Gardner added, noting she did not believe she witnessed the execution team perform a consciousness check on John Grant.

John Grant’s execution prompted Oklahoma’s Pardon and Parole Board to vote 3-2 in November to recommend clemency for Bigler Stouffer, who faced a December execution date. “I don’t think that any humane society ought to be executing people that way until we figure out how to do it right,” board member Larry Morris said. But Gov. Kevin Stitt (R) denied the board’s recommendation and allowed Stouffer’s execution to proceed.

By the time Donald Grant went before the state’s Pardon and Parole Board, most members had dropped their concerns over the state’s execution method. Only one member, Adam Luck, voted to grant clemency. Morris, one of the board members who recommended clemency for Stouffer, said during Donald Grant’s hearing that he was no longer concerned about the execution process after reading a decision from Friot.

Luck, who has been the subject of politically motivated attacks by proponents of the death penalty, resigned earlier this month at the request of the governor.

The lethal injection trial is expected to begin in late February. In the meantime, the state is continuing to kill people using a method that may soon be ruled unconstitutional, and the courts are unwilling to stop it.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies