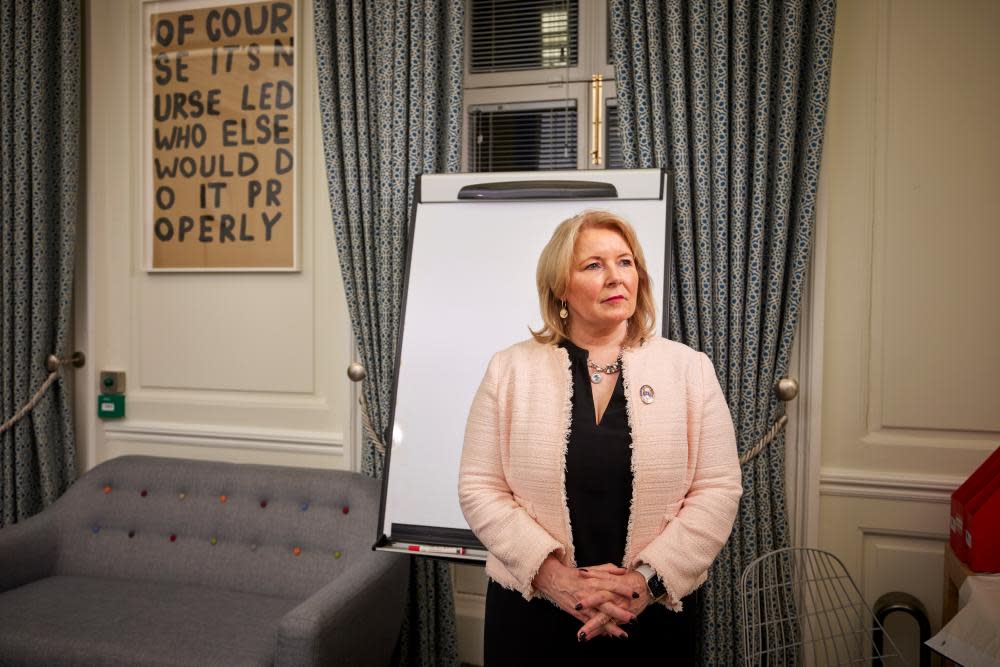

Nurses’ union leader Pat Cullen: ‘I follow through on what I believe in’

Pat Cullen tells a story that is very revealing about the character of the woman who is about to lead Britain’s nurses into their first-ever NHS-wide strike – herself.

Almost 40 years ago, back in 1983, Cullen was an 18-year-old trainee nurse at Holywell psychiatric hospital in Antrim, Northern Ireland. She was appalled that under its “token economy system” staff punished patients whose behaviour proved difficult by taking away their personal possessions – sweets, cigarettes, washbags or blankets.

“I felt it was totally unfair,” recalls Cullen, now 58, sitting in her office at the Royal College of Nursing’s (RCN) London HQ, decorated with photographs of nurses delivering many types of care. “These people were ill; they had mental heath problems. And some of these things that were withdrawn from them were very personal. I just felt that was such an injustice. Patients on the wards couldn’t cope without their own personal belongings.”

She took it upon herself to write to the hospital management raising her concerns. The result: the hospital softened, though didn’t scrap, its heartless policy. “I think I did win it; I felt great about it,” she says, then adds: “I felt so brilliant for those patients.”

Fast forward to December 2019 and her readiness to lead a fight against perceived injustice was evidence again when she led a strike by nurses in Northern Ireland, which at the time was the first stoppage in the RCN’s then 103-year history. She had become the RCN’s director in Northern Ireland just seven months earlier.

A key issue, then as now, was nurses’ salaries. “Nurses’ pay in Northern Ireland had fallen 10 years behind that of a nurse anywhere else in the UK,” recalls Cullen. “That for me was an injustice too far.”

RCN members worked to rule for two days and then withdrew their labour on a Monday, Wednesday and Friday one week.

A combination of the disruption to NHS care and, especially, pressure from a largely pro-nurse public forced the Stormont assembly, suspended as it so often is due to political wrangling, to resume sitting to thrash out a deal. The RCN won – not just better pay but also the introduction of Stormont legislation on safe nurse staffing levels.

Related: Nurses’ union leader accuses Steve Barclay of ‘bullyboy’ tactics

Cullen is the youngest of seven children – six girls, one boy – born to Paddy McAleer, a farmer in County Tyrone, and his wife, Annie. Remarkably, five of the six became nurses. Cullen credits the decision of her eldest sister, Bridie, 17 years her senior, to go into nursing for inspiring her and the others to do the same.

“I remember her coming home in her beautiful nurse’s uniform talking passionately to us as a young family about what she’d been doing on her last shift,” Cullen says. “I remember thinking, even at that young age, it was just incredible how much she was able to touch people’s lives.” The fact that her one non-nurse sister had a learning disability prompted her to go into mental health nursing.

The RCN’s impending action means that Cullen has little free time just now. When she does, she likes to use her sewing machine to make dresses and curtains and visit Portsalon, a picturesque town on Donegal’s less-visited east coast, not far from Derry.

How would she describe herself? She pauses. “I’m hardworking. I have a really wicked sense of humour. That gets me through. And I’m tenacious. I’m definitely tenacious. When I believe in something I’ll follow it through to the bitter end, I absolutely will.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies