Nick Galifianakis served NC in Congress, had history-making clash with Jesse Helms

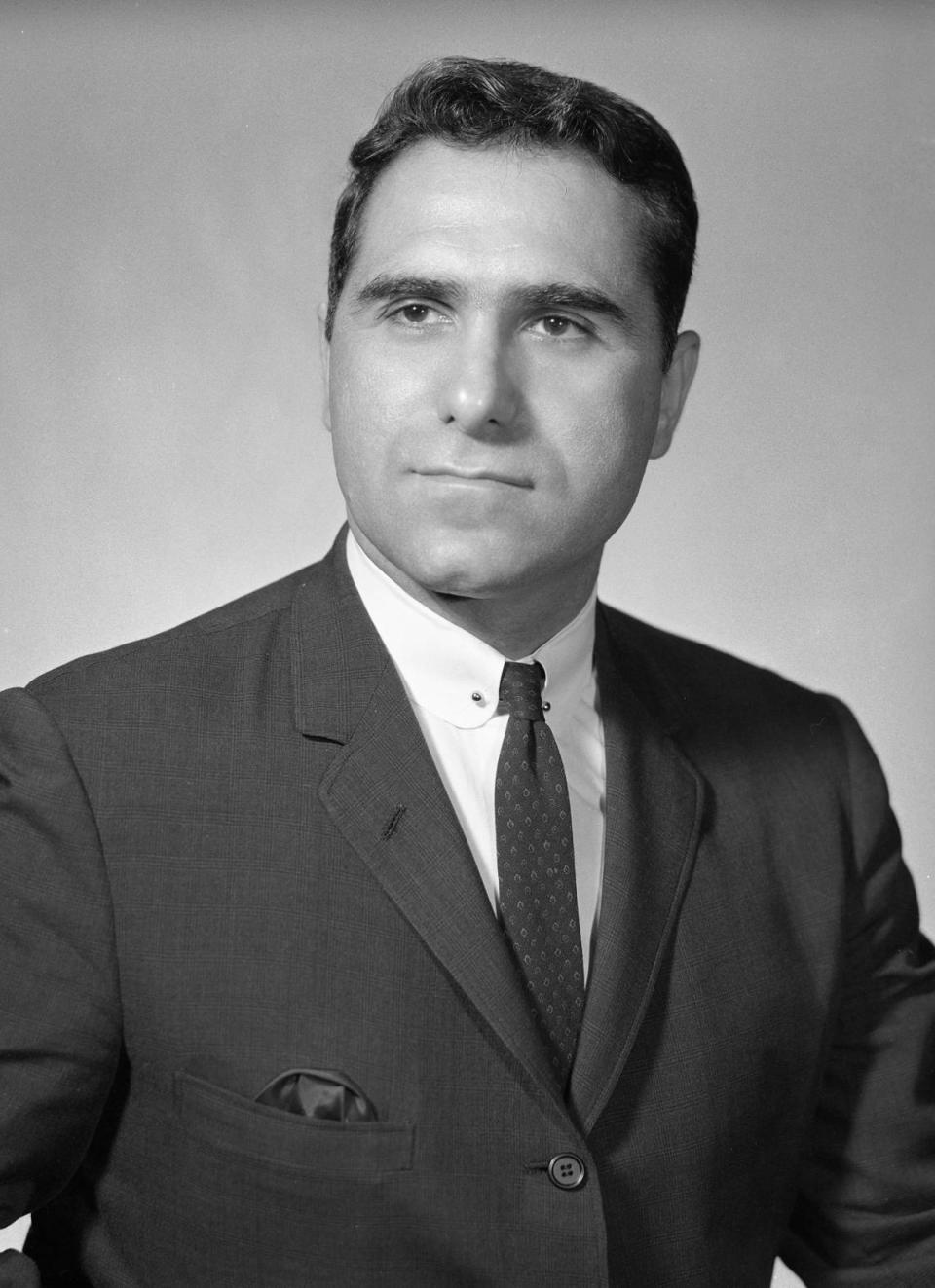

Former three-term U.S. Rep. Nick Galifianakis, once a rising star in the North Carolina Democratic Party, died at age 94 this week.

Galifianakis died in his sleep at his home at The Cardinal at North Hills, a Raleigh retirement community, according a family spokesman. He had been suffering from Parkinson’s disease for several years. Funeral arrangements were incomplete Wednesday.

At one time, Galifianakis was regarded as the hope of the moderate-to-progressive wing of the Democratic Party — a big strapping ex-Marine who could barely contain his exuberance for life or politics.

The Durham native had such a large personality — and long name — that his 1972 Senate campaign distributed matching buttons: One read “GALIFI’’ and a second read “ANAKIS.’’

On the stump, Galifianakis was earthier, telling voters that his name “begins with a gal and ends with a kiss.’’

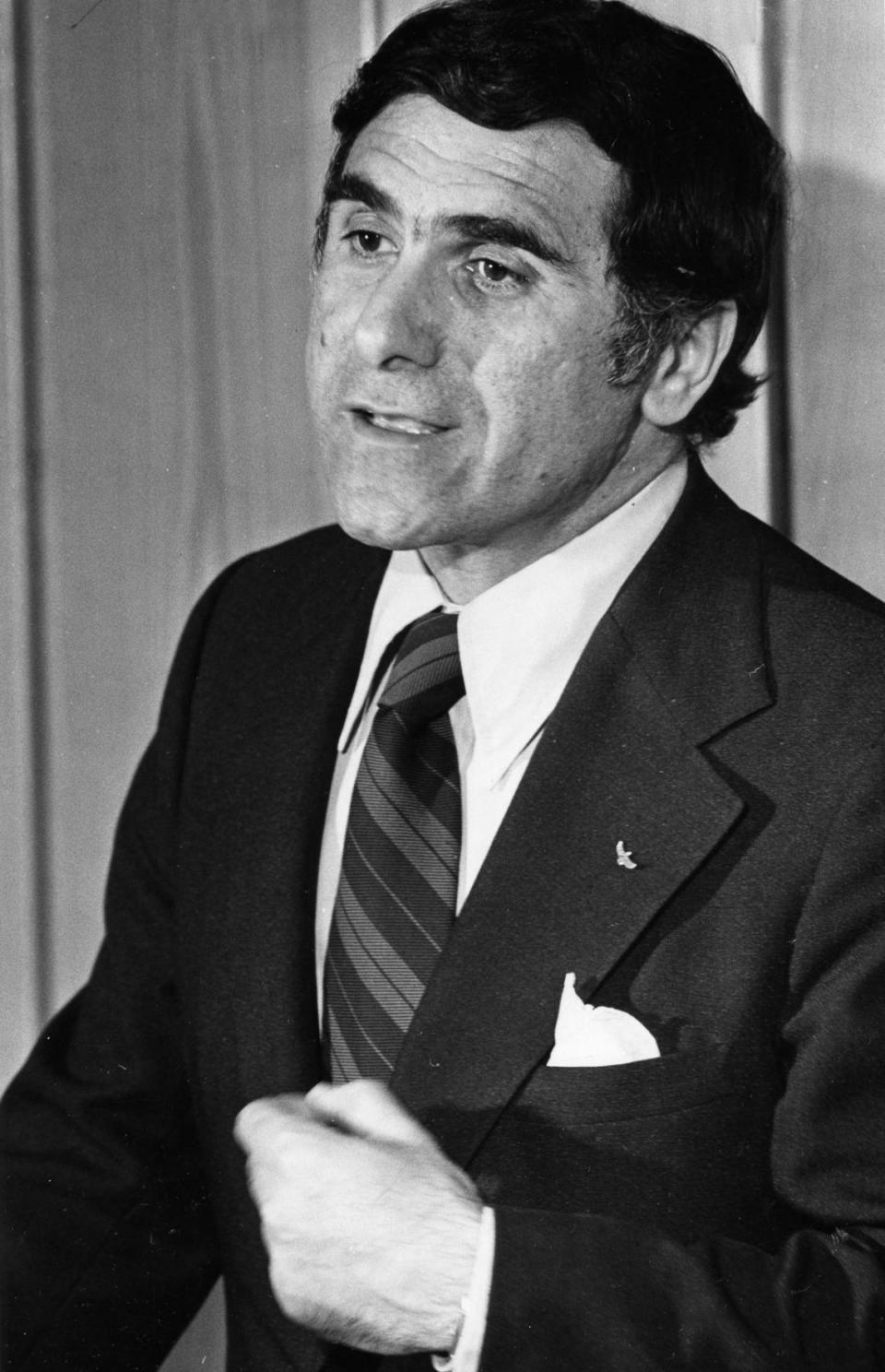

But his once promising political career derailed and was never quite able to get back on track after losing to Republican Jesse Helms in 1972.

Because he had been largely out of the public eye for decades, Galifianakis was nearly a forgotten figure by the time he died. A Google search of Galifianakis today is more likely to turn up information on two of his nephews — comedic actor Zach Galifianakis and Nick Galifianakis, a cartoonist with the Washington Post.

But in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, he was a figure to be reckoned with — Life magazine photographed him on the campaign trail, and a Doonesbury cartoon strip lampooned him when he became entangled in a scandal.

Galifianakis’s rise in politics

The son of Greek immigrants who operated the Lincoln Café on South Mangum Street in downtown Durham, Galifianakis was a scholarship student at Duke University where he earned both his undergraduate and law degrees. He served in the Marines after college, retiring with the rank of colonel in the reserves.

Practicing law and teaching at Duke, Galifanakis was encouraged by colleagues to run for the state House in 1960 — with 36 Duke colleagues each putting up 50 cents to pay his $18 filing fee. Although pushed into running, his biographer, historian John Semonche, noted that Galifianakis “seemed born to be a political animal.’’

He served three terms in the legislature, an ally of progressive Democratic Gov. Terry Sanford. He supported the creation of the community college system, and opposed the Speaker Ban law, which prohibited Communists and others from speaking on state-supported campuses. As House Judiciary Committee chairman, he oversaw the modernization of North Carolina’s court system — essentially the system that exists today — eliminating justices of the peace, and creating district court judges and an administrative office of the courts.

There was always a sense of fun about Galifianakis. Sponsoring a bill to abolish the death penalty for dueling, he brought two swords to the House floor and pretended to engage in combat with a colleague.

He also understood the power of publicity. Lobbying for the federal government to complete Interstate 85 from Henderson to Durham, he walked 19 miles along the proposed route in 1963.

In 1966, Galifianakis was elected to the 5th district seat in Congress, in a district that stretched from Durham to Winston-Salem. He defeated tobacco heir Smith Bagley in the Democratic primary. He was viewed as a moderate nationally, but his record put him on the liberal end of the spectrum in North Carolina. He supported the Equal Rights Amendment for women and became the first member of the North Carolina congressional delegation to oppose the Vietnam War. He also supported President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society anti-poverty programs. Galifianakis would later represent the 4th district after the legislature changed district lines.

When the legislature drew a less favorable district in 1971 — removing liberal-leaning Orange County — Galifianakis decided to challenge U.S. Sen. B. Everett Jordan in the Democratic primary.

Jordan, a former textile mill owner from Saxapahaw, was also a Democratic moderate. But Jordan, a gray and ailing figure, seemed like a figure out of the past. The 76-year old Jordan was fighting cancer and would die a little more than a year after leaving office.

Galifianakis won the Democratic primary by a 49% to 44% margin. But it turned out to be a prize of dubious value.

Jesse Helms and the 1972 campaign

His Republican opponent was Jesse Helms, a TV commentator for WRAL-TV in Raleigh, who was known for his sharply conservative take on school integration, the civil rights movement, and the liberal media.

North Carolina voters had never elected a Republican senator (although several were appointed by the legislature in the 1800s.) But Tar Heel politics were highly polarized, with the courts ordering school integration, campuses exploding with anti-Vietnam War protests and building takeovers, and the growth of the counterculture movement. During one six-month stretch in 1969, Gov. Bob Scott deployed the National Guard nine times to deal with civil unrest.

Galifianakis held a commanding lead early in the race. But a Helms media blitz tied him to the unpopular Democratic presidential nominee, George McGovern, and declared that Republican President Richard Nixon needed him in the Senate.

The Helms campaign purchased newspaper ads criticizing “McGovernGalifianakis welfare giveaways’’ and “McGovernGalifianakis cut and run’’ policies in Vietnam.

Galifianakis recalled one Helms campaign sign that read: “This is not Greece,’’ according to historian William Link.

Helms’ campaign slogan, “Jesse Helms: He’s one of us,’’ touched on Helms’ ideological conservatism, but also the ethnicity of the Galifianakis name in an era before North Carolina’s Sunbelt growth would diversify the population.

“The heritage of the white majority targeted by that message was largely English, Celtic or German,” wrote political scientist Tom Eamon. “But the name Galifianakis sounded alien. Helms was a safe North Carolina name going back for generations.’’

Galifianakis was also hurt by a divided Democratic Party, including angry Jordan supporters. Helms won so many conservative Democratic votes, that they were dubbed “Jessecrats.’’

Nixon carried the state by a 69% to 29% margin, winning all but two of North Carolina’s 100 counties. With Nixon campaigning at Helms side, Helms won by a 54% to 46% margin.

“Only a few elections truly represent major turning points in the history of a state or a nation,’’ Eamon wrote. “For North Carolina, the 1972 election was such an election…’’ Since then, Tar Heel Republicans have dominated senatorial politics, winning 14 of 18 races.

Scandal, retirement and the Peterson ‘owl theory’

The loss didn’t quite end Galifianakis’ career, but his star was now setting. He ran for the Senate again in 1974, this time losing in the primary to Attorney General Robert Morgan.

If there was any political life left in Galifianakis’ political career, the so-called Koreagate scandal tarnished it. The controversy involved a South Korean businessman and socialite named Tongsun Park, whose activities prompted a U.S. Justice Department investigation into whether Park was giving illegal campaign contributions and other benefits to members of Congress in order to influence American policy toward South Korea. U.S. officials suspected that Park was operating on behalf of a South Korean intelligence agency.

Galifianakis acknowledged receiving a $500 contribution, which he said he returned. But Park said a Galifianakis campaign aide visited his house to pick up $10,000 in cash — an assertion confirmed by the campaign aide. She said the money was mainly used to pay last-minute campaign expenses.

Galifianakis was indicted for allegedly perjuring himself before the House Ethics Committee, but a judge later dismissed the charges, saying the committee had failed to authorize the deposition in which Galifianakis had allegedly lied.

After the 1974 campaign, Galifianakis retired from politics and devoted his attention to his Durham law practice, which he kept open well into his 80s. His only political venture was to serve on the steering committee in 1988 of Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis, a fellow Greek-American. He attended the Democratic convention in Atlanta that year.

In later years, Galifianakis became a supporter — sometimes attending court hearings — of novelist and former Durham mayoral candidate Michael Peterson, who was accused of murdering his wife in a case that drew national attention. Peterson was convicted but later accepted an Alford plea, in which he did not admit guilt, for time served. Galifianakis, like some other supporters, was interested in the theory that an owl had caused Kathleen Peterson to fall down the stairs.

Galifianakis is survived by his wife, Louise, and two children, Jon Mark of Raleigh and Katherine of Washington, D.C.

Rob Christensen wrote about North Carolina politics for 45 years. He is the author of two award-winning history books and is completing work on a history of The News & Observer and the Daniels family. He can be reached at robchristensen1920@gmail.com.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies