‘Limonov: The Ballad’ Review: Ben Whishaw Stars in a Portrait of a Radical That Is All Swagger and No Game

That the name Limonov is pronounced “Lee-MWAH-nov” is one of two main things that Kirill Serebrennikov’s “Limonov: The Ballad” teaches us about Eduard Limonov, the Russian radical, poet, dissident, emigré, returnee, detainee, bête noire and cause célèbre who in 1993 co-founded the ultra-nationalist National Bolshevik Party. The second is that, as imagined in this adaptation of Emmanuel Carrère’s 2015 fictionalized biography, for all the shifting identities and attitudes he assumed over the course of his controversial life, his persona as an aggravatingly self-aggrandizing solipsist never wavered.

A sharper film could have excavated his contradictions to illuminating effect — the rise of populist, crypto-fascist political movements and their self-ordained maverick leaders being a not-irrelevant phenomenon these days. But Serebrennikov (“Leto,” “Petrov’s Flu”), in love with the posture of the rebel that Limonov adopted without being terribly interested in what, at any given moment, he claimed to be rebelling against, mistakes the trappings for the substance and seems to regard his salacious yet oddly sanitized biopic mostly as a delivery system for a rather dated aesthetic of DGAF cool.

More from Variety

Mubi Swoops on Andrea Arnold's Cannes Competition Entry 'Bird' for North America (EXCLUSIVE)

Cannes Awards: Female-Centered Stories Win Big in Cannes, as Sean Baker's 'Anora' Earns Palme d'Or

Chapter titles, rendered in faux Soviet-propaganda-poster font slam across the image as Limonov (Ben Whishaw), smirking in a stars and stripes shirt, announces in heavily accented English (the lingua franca of the movie no matter the actual language of the speaker) “I am an independent communist.” Time frames and aspect ratios shuttle back and forth: first we spring forward to a Moscow press conference that Eddie — as he likes to be called — is giving upon his return from exile in the Glasnost era. A woman in the audience explains her disappointment that his previous dissident image has apparently been replaced by that of “a bureaucrat. It breaks my heart,” she says. “I don’t care about your heart,” replies Eddie, enunciating clearly, and already now the faint suspicion arises that Whishaw, committed as he is, might have been miscast. As an actor, his great strength is the precise kind of soulfulness that Serebrennikov seems to actively discourage in his portrayal of this retrograde renegade.

Next we are back in the Soviet Union, in boxy black-and-white, where Eddie is a worker by necessity and a poet by passion, frustrated by the narrowness of his prospects for literary fame here in Kharkiv. His grandiloquent narration repeatedly expresses as much, along with assurances that greatness is his destiny, and that everyone around him is some manner of fool for not recognizing his genius. And so he decamps to Moscow, leaving his girlfriend Anna (Maria Mashkova) with nothing but a cartoon penis drawn on her backside to remember him by (“I know I’m bad” crows the narration). But in the capital too he can’t get published, and instead mopes around sulkily at literary soirées. Which is where he first encounters Elena (“Beanpole”‘s Viktoria Miroshnichenko) a leggy Anita Pallenberg cipher in a floppy hat and miniskirt who becomes Eddie’s paramour after he slashes his wrists in performative anguish at her rejection. Somehow the pair manage to get themselves exiled to New York City and soon they are frequenting the noodle shops and porn theaters of Manhattan in the ’70s, poor but photogenic and madly in love.

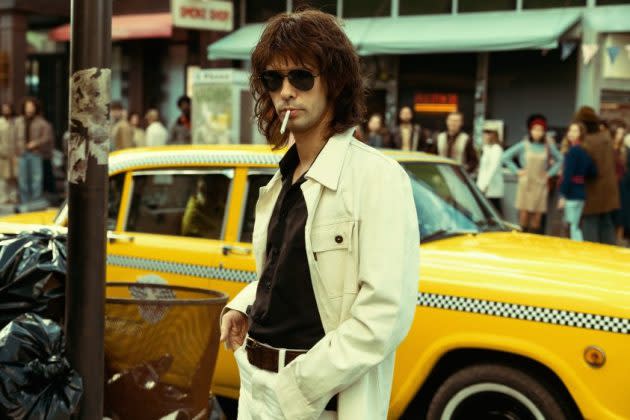

However Elena’s modelling career takes off, while Eddie spends his days wandering the streets of New York getting into fights with pamphleteers. Actually make that the street of New York: the set-built thoroughfare is impressively dressed by production designer Vlad Ogay but it is only that one street, giving a further air of pastichey theatricality to this whole segment. The inertia is increased by DP Roman Vasyanov’s curiously sluggish camera movement, by a Brechtian reality break and by the rather obvious movie references that Serebrennikov shoehorns in, to the point of having a young girl in a wide hat leaning in at the window of a yellow taxicab as Eddie and Elena exit the porn theater.

But then obviousness bedevils this movie, even as we follow Eddie through his stint as a butler to a millionaire, through his period of Parisian celebrity, his return to Russia, imprisonment and subsequent release into the embrace of the militantly nationalist fanbase he has accrued. And it’s a quality that lands particularly awkwardly in the film’s more dubious passages. A sexual encounter that Eddie engineers with a homeless Black man during the dark days after Elena leaves him, is a case in point: Eddie clearly gets off on the perceived sexual, racial and class-based transgressiveness of the act, but it is presented so bluntly here that we do not sense the film critiquing, or even particularly noticing, the queasiness of those assumptions.

Polish filmmaker Pawel Pawlikowski, credited here as co-screenwriter and executive producer, stated in a 2020 interview that after three years attached to this project as writer-director “I don’t really like this character, not enough to make a movie about him.” And perhaps Serebrennikov wanted to avoid the same disenchantment, which is why his film glosses over many of the more troubling incidents that Carrère’s book outlines. Instead, we get a ploddingly literal use of hip signifiers such as a character saying “Take a walk on the wild side” in a movie that actually uses the Lou Reed song as a cue, a repetition of the “Taxi Driver” reference in case anyone missed it first time around and a pride in the punk soundtrack as an indicator of edginess that doesn’t really gel in an age when you can buy Ramones T-shirts at H&M. Given all its omissions and elisions, and the sense of coolness-cosplay that permeates this noisy but lifeless film, “Limonov” might not be a total misapprehension of the mercurial, charismatic and infuriating Eduard Limonov, but it is at least a mispronunciation.

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies