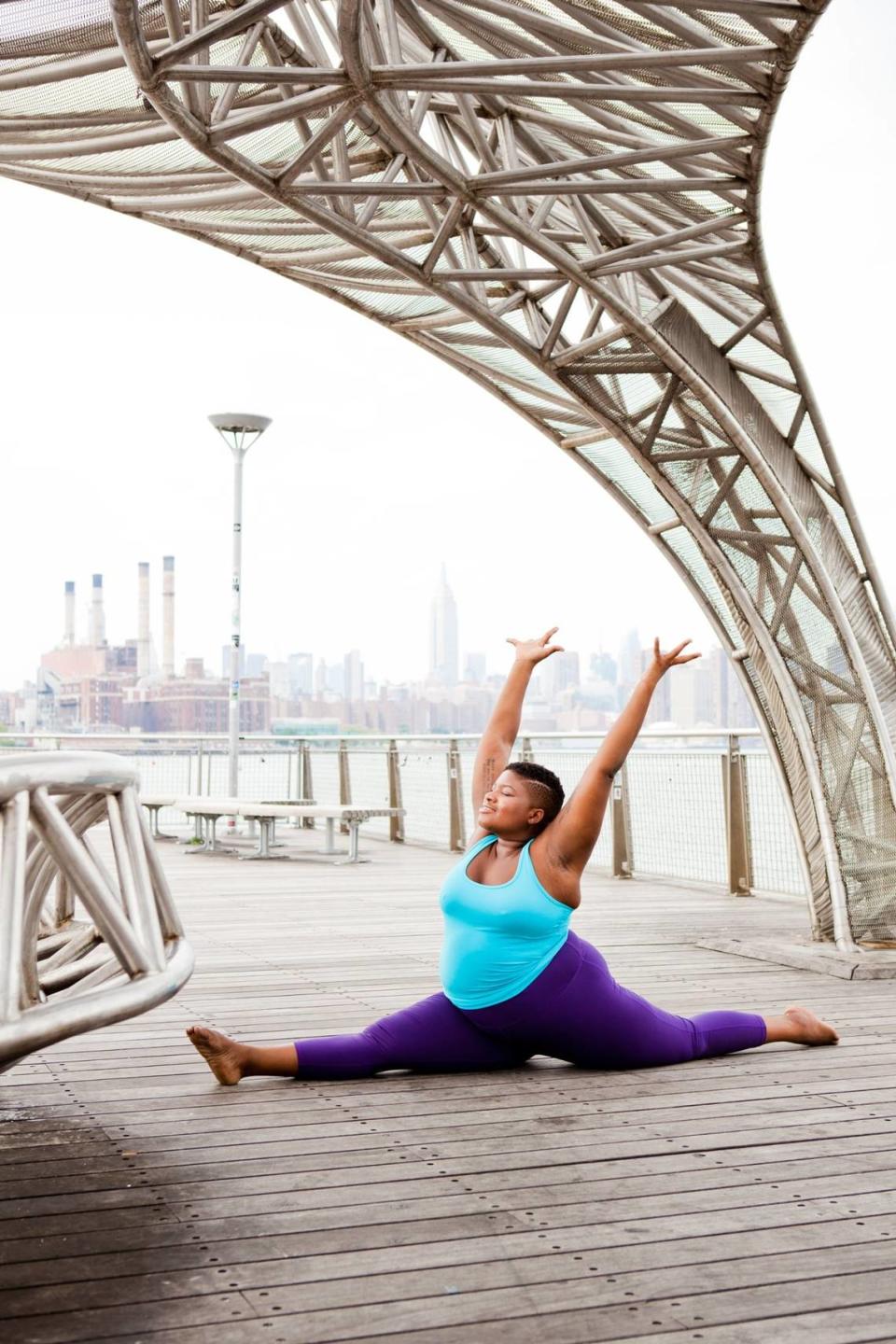

NC yoga instructor Jessamyn Stanley wants to talk acceptance — and the uncomfortable

In 2012, Jessamyn Stanley — an internationally acclaimed yoga teacher and author — was living in an apartment in Durham that was so small, she used her car as her closet, leaving most of her belongings in the vehicle and retrieving items from the parking lot as she needed them.

She had just moved to Durham from Winston-Salem with her partner, largely on a whim and seeking a change.

“I pretty much had a mid-twenties crisis. If you’ve been in your twenties, then you know what I was going through,” Stanley recalled as she laughed. “I was like, ‘I don’t know who I am, what I’m doing is not what I’m supposed to be doing.’”

Though Stanley had taken some yoga classes before, the classes in Durham were too expensive to attend regularly, so she thought yoga would be another hobby she’d just give up. Then, one day, she decided to unroll her old exercise mat — a hand-me-down from her father — on the narrow stretch of hardwood floor in her apartment’s living room. She performed the postures that she remembered from the classes she had taken.

And she realized that she could practice yoga alone.

Today, as Stanley approaches her 34th birthday on June 27, her life looks very different from 2012. She has become a social media star, accumulating nearly 500,000 Instagram followers, as well as high-profile partnerships with brands like Adidas.

She has traveled around the country and the world to teach classes and promote The Underbelly, her online yoga platform. She was named one of The Root’s 100 most influential African Americans in 2020, and is the author of two books, including “Yoke: My Yoga of Self-Acceptance,” which was published June 22.

In an interview with the News & Observer, Stanley spoke about “Yoke” — a collection of essays that blends memoir and philosophy — and about how the pandemic has affected her perspectives on everything from yoga to social media.

In conversation, as in her writing, Stanley is funny, honest and doesn’t pretend to be an expert on the topics she discusses. When she’s not sure about something, she talks it out rather than trying to neatly explain it. She shows the parts of herself that sometimes get lost behind hundreds of thousands of followers and 10-second Instagram stories.

Though she now has a national profile, Stanley remains an introvert who feels most comfortable spending time alone, she said.

In “Yoke,” Stanley grapples with this contradiction — the value she places on being alone and the value she places on connecting with others on social media. She also explores other tensions in her life. She writes about how relationships with teachers can help us grow and hold us back; the benefits and constraints of organized religion; the relationship between classical yoga and consumerist “American yoga.”

But Stanley does not try to resolve these tensions. Perhaps more than anything, she writes of the possibilities that arise when we make peace with these tensions, when we simply observe them, when we let them continue to exist.

Stanley still believes in the power of social media, despite its potential pitfalls — its ability to connect, to bridge, to make yoga more accessible to wider audiences and to facilitate self-understanding and change.

“It may seem like the digital age trivializes yoga,” she writes in “Yoke.” “But is the spread of compassion ever really trivial?”

Breaking down barriers

Stanley — who is Black and queer — is known for breaking down the stereotypes of what a yoga practitioner looks like, especially on Instagram.

“I think that a lot of people don’t go out to class because they don’t see themselves represented, which I understand completely,” Stanley said. “That’s why I was sketchy about yoga in the beginning.

“But the more people practice, the more we share community on social media, the more that conversations go from being about fashion and fitness and start to be more about the real change that can help us heal as a society.”

Stanley’s aunt invited her to her first yoga class when she was 16, a 90-minute long class in a 105-degree room. The class was so difficult that Stanley and her aunt required restorative Cookout milkshakes afterward — and Stanley avoided yoga for years.

When Stanley tried yoga again in her 20s, she realized much of her aversion to yoga stemmed from teenage angst. She started attending some classes when she was living in Winston-Salem.

But the biggest epiphany came when she started practicing alone in Durham — practicing at home gave her the freedom to exist beyond the gaze of others.

“I began to notice the difference between who I am in the privacy of my own identity and who I choose to be in front of other people,” she writes in “Yoke.”

But practicing alone at home ultimately led to Stanley’s large social media presence; it is why she now practices with more people than she ever would in a traditional yoga class.

After she established her home practice, Stanley started posting pictures of herself performing yoga postures on Instagram, hoping to get feedback from the online yoga community.

She has since attracted more than 250,000 followers collectively on Twitter, Facebook and her YouTube channel, and national publications like the New York Times have highlighted her message of body positivity and her insistence on including diverse body types in yoga.

While she now interacts with many more people than she did in 2012, she says her yoga practice has remained fundamentally the same.

“I don’t think I’ve ever really stopped practicing by myself,” she said.

Upending traditions

In March 2020, Stanley returned home to Durham after a trip to New York, where she had been promoting The Underbelly. She was used to traveling a lot. During her tour for her first book, “Every Body Yoga,” she often would wake up at 3 a.m. to travel to a new city.

Then, a week later, lockdown in North Carolina began, signaling the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. Stanley hasn’t traveled much from North Carolina since then.

“My initial feeling was deep gratitude to be still,” Stanley recalled.

In many of the essays in “Yoke,” Stanley writes about the ways that she upends the traditional values of mainstream American yoga. And though most of the book was written before the pandemic, Stanley says that the changes that have come with the last year-and-a-half have broken open the world of yoga, allowing for a reset as people rethink yoga’s purpose.

“American yoga has been really focused on fashion and fitness, rather than spirituality,” she said. “And I think that the pandemic has blown everything wide open, and made it clear that we have to take care of ourselves, and value self-care and healing as a way to heal as a society.”

For one thing, the pandemic has popularized online classes, where people can practice and focus on their own experiences, rather than what the person next to them is doing.

In her online yoga videos, Stanley often reminds her viewers: “It’s not that serious.” In a world where people often agonize over correct alignments or perfect Instagram shots, Stanley seeks to make yoga something else. She invites viewers to make the postures their own, to adapt and modify as needed.

It’s not that she thinks that yoga should be lower stakes, or that yoga is just something done to relax or feel good about ourselves. In fact, she thinks the work that yoga requires us to do, to self-reflect and understand ourselves in all our contradictions, should be hard.

But she believes in prioritizing inner reflection over external validation, in doing more fundamental change than becoming stronger or more flexible.

That fundamental change includes having more frank conversations about the role that race plays in the American yoga world. The movement for racial justice that ignited last summer helped facilitate these conversations — but Stanley said she hopes they will be more sustainable than surface-level change.

“I have heard more white yoga people talking about racism and Black Lives Matter and all these different things now than I have ever heard in my entire life,” she said. “But there’s a desire to do something on the surface. Anything that can be done on the surface is surface, it’s the least important thing. The most important thing has to be done within ourselves.”

Race in American yoga is a topic that Stanley covers in several essays in “Yoke,” and one that she has been thinking about for a long time.

“I think that living in the South, and always having lived with racism being pretty overt and a topic of conversation, has absolutely colored the way I approach American yoga,” she said.

Ultimately, she hopes that these conversations can make yoga in America more accessible, less about appropriating its South Asian roots and more about using it to better understand our own cultures.

“I think a lot of people in the South are still like, ‘Is this a cult? What is yoga, is this okay?’ Especially a lot of Black people feel that way, for sure — like, ‘This is sketchy, this is just for white people,’” Stanley said.

New Beginnings

In the coming months, Stanley will take part in a virtual book tour for “Yoke.” She also looks forward to teaching more in-person classes again.

As she continues to show up to her yoga practice for herself — just as she did in her tiny apartment in Durham nearly 10 years ago — she hopes that more people will feel inspired to start their own journeys with yoga.

“I don’t really think of myself as a yoga teacher. I think of myself as a practitioner, and I just show up to my practice every day,” she said. “I think that the way that you teach other people is to just exist.”

Stanley doesn’t see sharing herself and her practice with so many people as a necessarily long-term endeavor. Having such a large following on social media still feels foreign, she said.

“Teaching and sharing my practice with other people does not feel like something that’s a forever thing for me,” she said. “I don’t know how long I will teach and practice around other people. But I know that the universe is asking that of me now. So that’s what I’m doing.”

Although Stanley has been spending most of her time since last March at home, she is heading out on the road again soon. Stanley recently decided not to renew her apartment’s lease. She and her partner have bought a camper trailer, and they are packing it up for a road trip on which they hope to visit all 48 continental states. She plans to teach more in-person classes along the way and see where the trip takes her.

“I think a lot is going to change,” Stanley said.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies