Mysterious 'CUP' cancer took my mom. As science grasps for a cure, her spirit endures.

Most bobbleheads go up and down. Sitting on the dashboard, they nod along with the music you're playing as your car hums along. They're happy little things.

My own head goes the other direction. As cancer ruthlessly dragged down my mother this spring – less than two months between diagnosis to death – I often found my chin moving methodically from left shoulder to right, eyes bleary and cast down at the floor next to my mother's bedside, a physical manifestation of my disbelief.

This can't be right.

What in the world is happening?

Just six months ago, she and I danced to The Beatles at my wedding, not a care in the world. At age 72, she was in a time of life when many people start to slow down. Instead, she seemed to be gathering steam: active in various social clubs, volunteering for local political organizations, smacking the tambourine in the church band on Sundays, chasing her four grandchildren around more days than not.

She also wasn’t shy about going to the doctors. She never missed her annual mammogram, and messaged our family physician about nearly every knick or knock she felt in her body.

A body littered with cancer

In January, about four months before she passed, one of those little pains started growing into a big one. There was an ache in her chest, and it was getting worse. She was losing weight. At first, the doctors thought it was an inflammation of the cartilage around her ribs – eight weeks of healing should do the trick.

But it wasn’t getting better. By the end of February, she was nearly bedridden in pain. One afternoon in early March, a sudden, searing sensation in her chest caused her to jolt upright, and then head for the emergency room.

There, the doctors again nearly cleared her of anything serious. As a last check, one ordered a CT scan. That’s when they found the cancer, littered throughout her body: lungs, liver, ribs, sternum, hip.

One man's journey with cancer: I hate the pain. I hate the meds. I hate the incremental death.

My education on cancer began. Normally, I learned, doctors need to identify where a cancer originated, so they can select the right way to treat it. Certain cancers respond to certain chemotherapies, and others can be targeted by newer treatments like immunotherapy.

But that’s when the second bombshell landed. The doctors had no idea where my mother’s cancer came from.

She steeled herself to endure a bone biopsy of her hip, then a second liver biopsy, then a fancy blood test to try and ID what kind of cancer she had, or at least a semblance of genetic material. All came back empty.

The doctor’s ultimate diagnosis: “Cancer of unknown primary origin.” Or “CUP” cancer, an acronym so confounding it makes me wonder if its originator picked a random object in the room and thought, that'll do as good as anything.

Columnist Connie Schultz: My front porch is my summer sanctuary. I find happy memories, hope and peace out there.

Here are the traditional theories. Somewhere in my mother's body was a tumor so small it escaped detection. Or, perhaps it was once there but was destroyed by the immune system, or inadvertently clipped out during a surgery for something else.

But at some point, it sloughed off its cells and they metastasized all over her body. These tumors, in turn, mutated for so long, undetected until they began to fracture her bones, that they no longer had enough identifiable genetic information to determine where they originated.

That left the only treatment option as a “broad spectrum” chemo, a shoulder shrug of a plan that involved throwing everything but the kitchen sink at the tumors. The doctors recommended breaking the dosage up over three weeks, instead of the usual one week, just to avoid killing her outright.

We never even got that chance: My mother collapsed at home three weeks after diagnosis, a week before chemo was to begin. It was home hospice from there.

Grim prognosis for rare cancer

A similar fate apparently befalls the 2-3% of cancer patients who are ultimately diagnosed with CUP, or about 30,000 people in the United States each year. Because CUP is always diagnosed after the cancer has spread, prognosis is grim, with median survival rates of two to 12 months. That basically puts CUP neck-and-neck with stage 4 pancreatic cancer for the worst possible thing you can get.

Yet, it's hard to believe there are even that many people with CUP. Nobody in my family or our social networks ever encountered it. Looking for perspective, I explained the situation to my own doctor, a sage-like, 77-year-old private practitioner who has heard of everything.

He responded, “I've never heard of that.”

In a world of online everything, there is frighteningly little on Google and Facebook about CUP cancer. Most medical information is housed on United Kingdom government websites, and it's more or less limited to everything I just explained. There are one or two sparse support groups, with a few hundred members, and a zebra-striped awareness ribbon that I presume somebody created themselves in a moment of frustration.

Signs of hope? A moment for measured optimism in the ongoing battle to tackle pancreatic cancer

In my own despair, I performed deep research into the latest medical research on CUP. It only further confounded me. As it turns out, a new school of thought cuts against the long-standing belief that CUP is a “catchall” diagnosis for diverse cancers with a missing primary tumor. Instead, some theorize that CUP is a kind of cancer all of its own, originating systemically from developing cells, like a blood cancer.

In other words, the origin of cancer of unknown primary origin is unknown. Commence head shaking.

I did find one spark of hope. Last year, a group of Italian researchers led by a Dr. Carla Boccaccio published a study. They grafted human CUP tumors onto mice, and suspecting a certain genetic mutation is common in such tumors, gave the mice an already-approved chemotherapy drug that targets it. In an email correspondence, Boccaccio told me that the results indicate potential 70% effectiveness against CUP cancer, leading to their development of an upcoming clinical trial in Italy to try it out on humans.

I rushed to get the information in front of my own mother's doctors, desperate for anything that might work. But there were too many unknowns, and too little time.

My mom never gave up on us or science

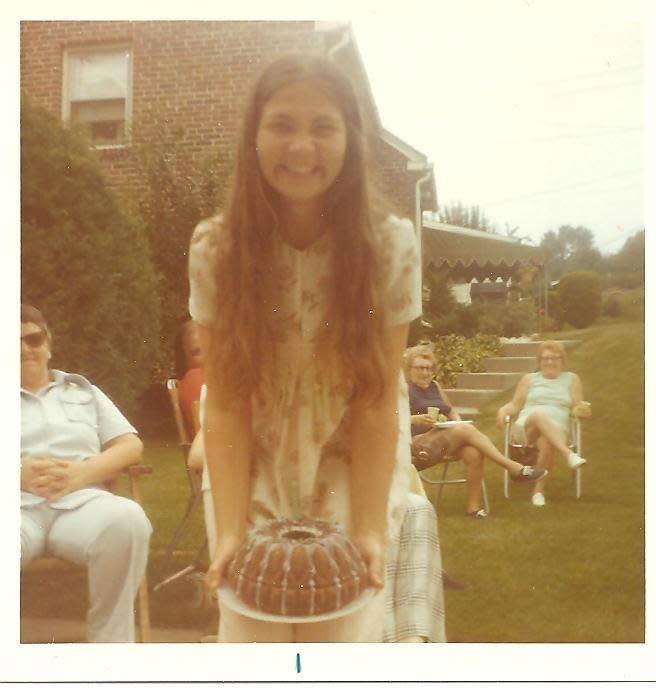

Cheryl Taylor Bagenstose passed away on April 24 at age 72, six months to the day after our mother-son dance, and seven weeks after diagnosis.

How in the world that can happen, I'll never know.

Here's what I do know. My mom was an incredible person. She taught art in public schools for more than three decades. Was happily married to my father for 50 years. Raised three kids and loved her four grandchildren. Was more active even in her final months than I ever was or likely ever will be.

In her early 20s, my mom took a semester off college to care for her own mother as she passed away from breast cancer. After ovarian cancer took my dad's mom about a decade later, he told me they found some comfort in science: “By the time we grow old, surely they'll have a cure for this,” they believed.

Former surgeon general Jerome Adams: After COVID-19, our next big health care challenge will be drug-resistant infections

My mom never gave up on science, in fact, she donated her body to it. We're also working on getting her biopsies to Dr. Boccaccio to aid in her research on CUP cancer.

But more important, my mom never gave up on us.

Toward the end, knowing she was rapidly slipping away, I sat by her bedside and grasped her hand, distraught. We hadn't had meaningful communication in days, and I didn't expect any then. But almost as if sensing my pain, buoyed by the awesome power of a mother's love, she swam up from the depths of wherever end-stage disease drags you and opened her eyes. Bright blue, they locked right onto mine.

I told her that I was lost, but that she had already shown me the way forward. That I'd never get over the tragedy that cancer inflicts, but that she demonstrated how to keep living. That you keep smiling, keep going, keep dancing, keep loving and growing the family that remains.

She nodded as I spoke, gripping my hand firmly, her eyes crystal clear and reassuring. We said our I love yous. Exhausted, she closed her eyes and immediately sank back down below.

Maybe by the time I'm her age, CUP will not only no longer be unknown but also unimportant. Banished with the rest of cancer into the ignoble trash bin of has-been diseases.

But if not, my mother gave me the blueprint for how to endure, and a love that will never die. That much I know.

Kyle Bagenstose covers environmental topics for USA TODAY, specializing in water, chemicals and climate change. Follow him on Twitter: @KyleBagenstose

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Rare CUP cancer with no known origin or treatment plan killed my mom

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies