They are the NFL's most-honored players. Why did their nonprofits often spend so little on charity?

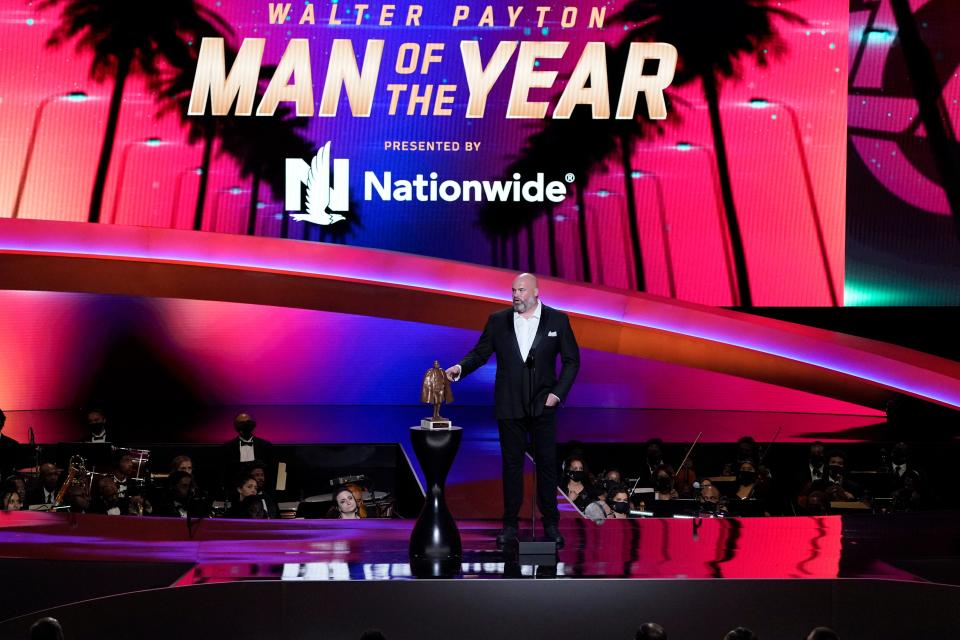

Russell Wilson wore a wide smile and tuxedo a year ago this week as he strode to center stage at the YouTube Theater in Inglewood, California, to present the National Football League’s most prestigious individual award.

The Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year, first conferred in 1970, celebrates excellence on and off the field, with an emphasis on community service and philanthropy.

Wilson, the 2020 recipient and then-quarterback of the Seattle Seahawks, had the privilege to introduce his successor, Andrew Whitworth, then an offensive lineman for the Los Angeles Rams, at the annual NFL Honors awards show just days before the Super Bowl.

The men embraced onstage to a star-studded standing ovation.

Both players had founded nonprofits to lead their charitable efforts.

And both organizations, according to federal tax records, were paying employees more money than they spent on charity.

“What’s actually crazy about this subject,” Whitworth told the USA TODAY Network about professional athletes in the nonprofit sector, “is I don’t even know how much the players or people actually know how much is going on, or what exactly they’re signing themselves up for in that sense.”

The 2022 Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year will be announced at NFL Honors on Thursday night at Symphony Hall in Phoenix. The event is hosted by Kelly Clarkson and will broadcast live on NBC, NFL Network and Peacock.

The winner receives the Gladiator statue — a gleaming bronze trophy of a football player wearing a cape — a special patch to wear on his jersey for the rest of his career and a $250,000 donation to his charity of choice from the NFL Foundation and Nationwide, a corporate sponsor. The other 31 nominees, one from each team, each receive up to $40,000.

Twenty-three of the past 26 Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year Award winners have founded a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization since the award was named in honor of Payton, the 1977 recipient, shortly after his death in 1999.

The USA TODAY Network spent six months reviewing thousands of pages of federal tax returns and state records filed by the nonprofit organizations founded by these esteemed men, including five with connections to the Arizona Cardinals — J.J. Watt, Calais Campbell, Anquan Boldin, Kurt Warner and Larry Fitzgerald. The USA TODAY Network also spoke at length with recipients and their families, nonprofit accounting and legal experts, the NFL, the NFL Players Association and those who represent the athletes and their organizations.

The investigation found the NFL trumpets its players’ philanthropy and community service with the full force of its extraordinary marketing might and has built the Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year award into a monument to excellence. But the NFL does not vet the nonprofits founded by the men it honors — teams are responsible for vetting their nominees, league spokesperson Brian McCarthy said. And neither the NFL nor the NFL Players Association, which presents weekly and annual awards for community service, educate their players on the nonprofit sector with equal vigor.

The resulting knowledge gap, mixed with players’ bravado, societal expectations and the encouragement such awards provide to give back to the community, often lead players to found nonprofit organizations that stumble for years, award winners and nominees said.

“It’s not as simple as saying, ‘I want to help people,’” Watt told The USA TODAY Network. “I wish it was. Trust me. I wish it was. But you have to understand the responsibilities that come along with it.”

Players often enlist family, friends and business associates who mean well but are inexperienced and ineffective at running a nonprofit, which can result in strained relationships and fundraising events that generate positive media attention and accolades but little to no money — or even lose money — a common occurrence.

Or players are directed by their agents, publicists and marketing representatives to hire for-profit management companies like Prolanthropy LLC, which counts two Payton award winners and more than 30 nominees among its current and former clients — and bills itself as the “largest and most successful provider of full-service philanthropy management in professional sports.”

But the company has charged its managed nonprofits 22.5% of total revenue — regardless of whether it raised the money — according to contracts obtained by The USA TODAY Network.

That percentage is “wildly out of line” with industry norms, according to nonprofit oversight attorney Andrew Morton, a partner at Handler Thayer LLP and chair of the firm’s sports and entertainment philanthropy group. He said most competitors charge between 5% and 10%.

Experts likened Prolanthropy’s business model — in which it charges a large percentage of total revenue and handles all operations — to the company having an equity stake in its managed nonprofits and said such an arrangement can lead to abuses, reward without merit and undermine the integrity of the nonprofit sector.

Prolanthropy also has charged its nonprofits 20% of the “fair market value” of in-kind donations, its contracts show — which is legal but a rarity in the nonprofit world, experts said — then spends lavishly on overhead, often leaving far less than 50 cents of every dollar for charitable activities, according to tax records.

National charity watchdog groups including CharityWatch, Charity Navigator and the Better Business Bureau Wise Giving Alliance expect efficient nonprofits to spend at least 65 cents to 75 cents of every dollar on charitable activities. The best spend far more.

Andrew Stebbins, an attorney representing Prolanthropy, released a statement to The USA TODAY Network that described the company’s clients as “business savvy,” and said Prolanthropy provides athletes “peace of mind” that its nonprofits will be “managed effectively and professionally.” This includes “working with our client’s agents and legal representatives to ensure that all portions of the management agreement are understood and fit what the client is looking for in a foundation management company.”

Retired Chicago Bears cornerback Charles “Peanut” Tillman said he left Prolanthropy after the company took a cut of the prize money when he was named the 2013 Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year. His Cornerstone Foundation, which reported record revenues and expenses in 2014, spent just 26 cents of every dollar on charitable activities that year, its last under Prolanthropy management, according to tax records.

Tillman said he refused to sign a non-disclosure agreement and reported the company’s business practices to the NFL.

“Everything you said, that was me too,” Tillman told The USA TODAY Network. “That’s all players. They might not know everything about the foundation business, but they want to give back. They want to use their platform to do something amazing. I tried to tell people, ‘Learn from my mistake.’”

Prolanthropy said it has recently reduced the amount it charges for donations from unsolicited, viral social media campaigns and now gives clients the option to vary, limit or exclude “fee percentages for in-kind donations, athlete donations, and other financial support,” Stebbins wrote. These changes were enacted following this reporter’s investigation into the company’s business practices for The Buffalo News in 2021.

Prolanthropy refused to answer written questions from The USA TODAY Network about a half-dozen of its managed nonprofits.

“A contractual non-disclosure agreement binds us,” Stebbins wrote, “and we hold our client’s privacy in the utmost regard.”

In undertaking this investigation, The USA TODAY Network sought to explore how professional athletes engage in philanthropy. Focusing on the NFL, our reporting looked at how much guidance and education was available, what best practices and common pitfalls exist, experience and knowledge from veteran players and experts on nonprofits, and what might the NFL and its players’ association attempt to increase nonprofit educational initiatives, which would serve the best interests of players, donors and beneficiaries.

“There are better ways of doing things,” Campbell, the 2019 Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year and NFLPA vice president, told The USA TODAY Network. “With the knowledge that a lot of us have accumulated over the years, the older players, we need to figure out a better way of doing things to change the system so that the younger guys can do it easier — and more efficiently — and help the people they really want to help.”

To be sure, some players’ nonprofits are efficient. And countless well-meaning athletes, including those whose efforts were examined for this report, are generous with their time and platforms and donate large amounts of their own money to well-established organizations.

Insofar as The USA TODAY Network could determine, none of the nonprofits founded by Payton award winners have been accused of running afoul of tax rules by the IRS or other authorities. And there is no legal requirement that a certain percentage of spending must be on charitable activities.

A recurring theme that emerged was ignorance leading to inefficiency, not corruption.

A nonprofit’s efficiency is often more important than the amount it raises, experts said.

“There are a lot of guys that are in that position that they’ve always dreamed of being in,” said Boldin, the 2015 Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year, “and they finally have the opportunity to give back and be helpful, but a lot of guys don’t know where to turn. Guys don’t know where to start. And a lot of times when you ask people who you trust, they don’t even know.”

Boldin’s Q81 Foundation spent just 25.5 cents of every dollar on charitable activities during its first five years in Arizona, according to tax records, in part because it lost nearly $75,000 on fundraising events from 2007-09.

To be clear, the Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year award and the NFLPA’s Alan Page Community Award are not bestowed solely based on the advertised impact of a player’s nonprofit. But winners of both awards said they have received questionable, if any, guidance on the nonprofit sector, and the information vacuum persists throughout locker rooms today.

“It’s kind of cliché that you get into the NFL, you start a nonprofit,” said Felecia Edmunds, the mother of three NFL players and president of the My Brothers Keeper Foundation, which like most players’ nonprofits reports less than $50,000 in annual revenue, an amount that requires few public disclosures to the IRS.

Larger organizations must provide far more financial details, and federal tax returns are posted online for public inspection.

The Russell Wilson Foundation, which does business as the Why Not You Foundation, reported it spent almost $600,000 — or just 24.3 cents of every dollar — on charitable activities in 2020 and 2021 combined and nearly twice as much, $1.1 million, on salaries and employee benefits in that span, according to federal tax records.

These expenses included $342,000 for an executive director and more than $430,000 for a second executive who also worked for the Wilson family office, the nonprofit confirmed, a relationship not disclosed on federal tax records, as required by law.

This raises questions about private inurement — a criminal abuse of power resulting in personal gain from a nonprofit’s resources — according to nonprofit legal and accounting experts who spoke with The USA TODAY Network.

Wilson’s agent and attorney, Mark Rodgers, said the second executive spent the “vast majority” of his time working for the nonprofit and argued both salaries were reasonable and justified based on third-party fundraising by partner organizations.

“The 990 (federal tax form) doesn’t reflect entirely the impact of the Why Not You Foundation and the work that the executives completed on behalf of the Why Not You Foundation,” Rodgers said.

Whitworth’s Big Whit 77 Foundation reported it spent more than $33,000 on salaries and other compensation and less than $20,000 on charitable activities from 2019-21, the last three years for which federal tax records are available.

Just 35.3 cents of every dollar spent in that span went to charity.

“What we’ve done over the last few years hasn’t been what we set out to do,” Whitworth told The USA TODAY Network about his nonprofit. “And we really haven’t been, quite honestly, trying to keep it. We’ve been honest in the process of trying to shut it down.”

Campbell, a former Cardinals draft pick who played nine seasons with Arizona, said he and his family did little research about the nonprofit sector before founding the CRC Foundation in honor of his late father in 2011.

The CRC Foundation celebrity golf tournament in Phoenix lost money in three of four years and $26,000 overall.

“Raising money was a lot harder than we thought it would be, based on what I had seen other people doing,” Campbell told The USA TODAY Network. “It took a little while to figure that out. And even then, I worked really hard to try to put on really great events and we ended up breaking even because the people who put the event on for you, their piece would be the bulk of the profits.

“It’s a broken system from that standpoint right now.”

The NFL provided The USA TODAY Network with a four-page document created by the NFL Foundation titled “Starting a player foundation — considerations and helpful tips,” which it said it has distributed to all 32 teams and to players on the rare occasion one asks the league for nonprofit guidance.

“Many professional athletes want to start their own non-profit foundations …” it begins.

The second paragraph, in bold, says: “However, not every NFL player should start a 501(c)(3) foundation.”

The NFL does not require its teams to distribute this document to its players, but they can choose to make it available, McCarthy said.

The NFLPA’s Alan Page award recognizes a player who goes above and beyond to perform community service and comes with a $100,000 donation to his nonprofit of choice.

NFLPA spokesperson George Atallah said the union always stresses the importance of financial literacy, encourages its members to consult a registered financial adviser for guidance on the nonprofit sector and offers a hotline to its security director, who provides free background checks on people and organizations upon request.

“I think if the NFL or the NFLPA have resources,” Boldin said, “they can do a better job of making it known to the players. And on the other end, players have to do a better job of reaching out to see if there are those resources.”

There is no formal nonprofit education provided by the NFLPA to active NFL players, Atallah confirmed, despite the possible repercussions of its members mismanaging tax-exempt organizations, including inefficiencies that deprive the people a player aims to help, public relations nightmares and the potential for crimes like private inurement.

“Every year in camp there’s mandatory meetings that have to be had, right?” Whitworth said. “So why isn’t that one of them? I spent 45 minutes watching a video, ‘Why not to beat my wife.’ You know, ‘Don’t do domestic violence.’ ‘Why not to drunk drive,’ for 45 minutes. ‘Why not to carry a gun on you in an airport,’ for 45 minutes. All of these, I call them, ‘covering your ass-type things.’ And every year I have to watch this video because I’m on a team. And I’ve done it for 16 years.

“Why isn’t there a video or a session on 501(c)(3)?”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: NFL players' nonprofit fundraising doesn't always reach those in need

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies