Moncton poet brings Black history to young francophone audience

The Frye Festival is underway in Moncton.

The annual bilingual literary celebration began Friday and runs until April 25.

This year's lineup includes acclaimed authors like André Alexis, whose 2015 novel, Fifteen Dogs, won the Giller Prize, Canada Reads, and the Writers' Trust Fiction Prize, and Madeleine Thien, whose critically acclaimed novel, Do Not Say We Have Nothing, won the Giller and a Governor General's Award in 2016.

Some of the other names generating some excitement include Francesca Ekwuyasi, whose debut novel Butter Honey Pig Bread is a CBC Canada Reads contender and was longlisted for the 2020 Giller Prize, and Amanda Leduc, author of Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space, as well as the novels The Centaur's Wife and The Miracles of Ordinary Men.

For a second year in a row readings are taking place online via the festival's YouTube channel.

The program can be found at Frye.ca.

Felt connected to Africville's story

On the final day of the schedule, Moncton spoken word artist and singer Josephine Watson, who previously was the Poet Flyée at the Frye festival for two consecutive years, is expected to read her new French translation of Shauntay Grant's children's book, Africville.

"It's actually a bit of a dream come true," said Watson, who always wanted to be involved with children's books and is working on one of her own.

As a Black woman who grew up in Fredericton, Watson says she "really connected" with the story.

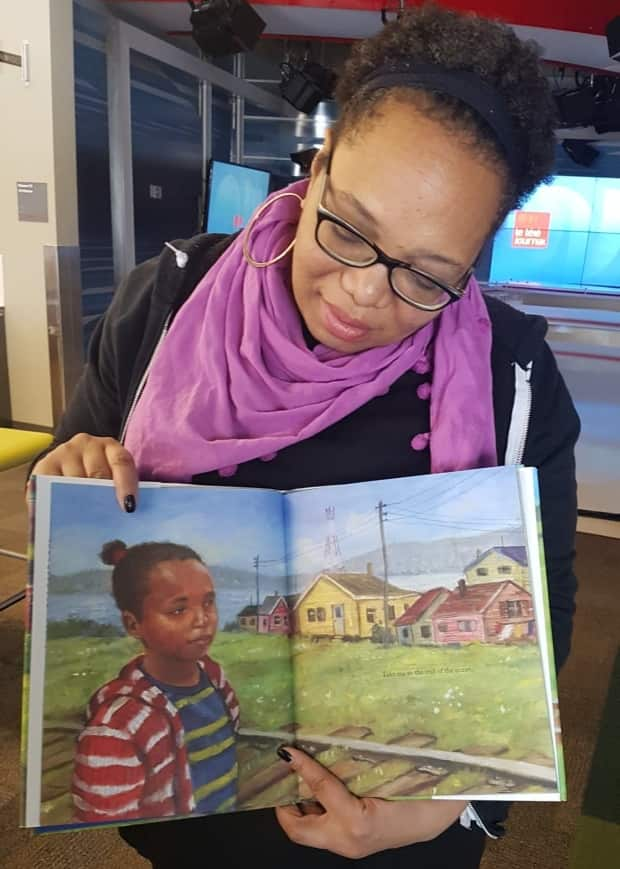

"When I opened that book, it became extremely personal to me. There's one photo at the very beginning of a young black girl in the Maritimes. And for me, that's an image that I never saw before. And I'm 50."

Watson wishes the book had been around when she was a child.

But she's pleased about the way things worked out.

"That little girl that's inside me not only gets to read the book, but to be able to participate in a project that's just so beautifully written and beautifully illustrated as well … it's been an honour."

The history of Africville is a tricky subject for a young audience.

"It really was sort of a really horrible thing that happened to people in Halifax," said Watson.

Africville was a predominantly Black community that existed in north end Halifax from the early 1800s until the 1960s.

Its residents paid municipal taxes but had no running water, sewerage or emergency services. Undesirable facilities like a slaughterhouse, infectious disease hospital and dump were located nearby. City council eventually decided to get rid of it altogether.

"The whole community was razed," recounted Watson. "The people were pushed out of their homes. Their homes were destroyed."

It's a very serious issue, she said, but it's approached in this book with a sense of adventure.

A little girl visiting the modern-day park where Africville used to be imagines the fun her ancestors had "in this beautiful little area with berries and families and playing on Tibby's Pond."

"It's quite joyful," said Watson, "even though it's a heavy story."

Watson also enjoyed the opportunity to write in French.

She's an anglophone who learned French as a second language through a French-immersion program in school. That's something she considers a "blessing."

"Being able to speak French at a young age when other students couldn't speak French was a very special gift for me. It gave me a little bit more power and a little bit more self-confidence."

She found the language came quite easily to her.

But translating isn't just about taking an English word and turning it into French, she said.

You literally have to go into the culture of that language to find its closest equivalent, because you might never be exact - Josephine Watson

"You really have to make sure that you're choosing the right expression."

She tapped into her theatre experience to try to get into the character's head.

Watson is a graduate of the professional theatre program at Dawson College in Montreal. She toured with Geordie Productions and Village Theatre. And she taught theatre and movement at the Black Theatre Workshop's youth program.

"When I see a performance in French or I hear music in French, I'm in a completely different mindset."

She also got some valuable help from editor Marie Cadieux.

In English, Shauntay Grant's character talks about the smell of blueberry duff, for example.

For the local francophone audience, that became grands-pères aux bleuets.

"You literally have to go into the culture of that language to find its closest equivalent, because you might never be exact."

"It's not only the language that is different, but it's the culture that is different, the understanding of how you live, how you proceed, how you treat others, the food you make, the clothing you wear, it's all different."

For more stories about the experiences of Black Canadians — from anti-Black racism to success stories within the Black community — check out Being Black in Canada, a CBC project Black Canadians can be proud of. You can read more stories here.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies