A New Mexico school sent all kids back in person in one day. We followed a teacher to see how it went.

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. – More than 150 days into the school year, teacher Stephanie Davy kept repeating the same cheerful greeting to students:

"Hi – Who are you?"

Davy couldn't recognize most teenagers in masks at West Mesa High School because it was only the second day of in-person learning in Albuquerque Public Schools. For 13 months after the COVID-19 pandemic closed buildings in March 2020, instruction had happened fully remotely, with students showing up as colorful bubbles on a screen because nobody turned on their cameras. Others never logged in at all.

After months of debate about how and when to reopen schools, Albuquerque returned to full-time instruction on April 5. But unlike other districts, it reopened all grades at all buildings all at once. And it let USA TODAY follow a teacher for a day to show what a return to high school looks like.

Widespread concerns about students' academic decline and social isolation are driving the push to return to full-time instruction nationwide. Large districts have struggled the most with reopening buildings, but with vaccinations up and infections down, many are bringing back students for five days a week of instruction this month, mostly in waves led by younger grades.

Albuquerque's rapid switch to offering full, in-person learning for its 75,000 students portends the benefits and challenges ahead for other large districts, particularly when it comes to opening high schools.

Despite mitigation tactics and many students choosing to stay remote, Albuquerque had 35 cases of COVID-19 involving 16 schools by the end of the first in-person week.

But reopening buildings also allowed teachers to make important connections with students, including many who were absent all year. Between April 5 and summer break, they would have a potential 37 in-person days to nurture students' growth and prepare them for fall, when the most serious academic recovery will begin.

"Nobody knows how anything is going to go day to day," Davy said at the end of her first day back with students. "But on Monday I had some kids walk into my class who haven't participated all year."

She went to bed that night feeling hopeful it would happen again.

Back to class, day 2: Tuesday, April 6

6:36 a.m. – Davy started the morning of the second day of in-person school with a brief workout inside, instead of her usual morning jog. She picked up running during quarantine. The routine helped stabilize her mentally, and she also shed 30 pounds.

"I feel like I'm being a good example for my student-athletes," she said.

Davy, 35, teaches health, child development and a dual-credit class for students who might want to become teachers. She also coaches cheerleading and track and oversees the gymnasium during basketball season. She earned degrees in health and exercise science and a master's in sports administration before pursuing teaching as a second career. The energy she brings as a mentor, coach and advocate, combined with an irreverent sense of humor fluent in TikTok and teenage ribbing, tends to motivate even the most reluctant students.

But she struggled during remote instruction. Teaching from home, with her daughter attending pre-K by Zoom in another room, Davy noticed students she could normally entice were silent on screen or absent. She felt her own energy wane.

"I'm not an online teacher," she said. "I need to be in class."

On April 5, the first day back, a district internet outage led to major challenges for teachers trying to juggle in-person and online students at the same time from their classrooms. Davy was less bothered than some of her colleagues; she never expected reopening to be totally smooth.

After getting ready on April 6, she prepped snacks for herself, then whisked her giggling daughter BrynnLeigh, 5, into the bathroom to style her hair.

"Now you need something to eat, ma'am," Davy said. "You also need your mask and a jacket."

Then Brynn and her father, Tyler Davy, were out the door – Brynn to pre-K and Tyler to his landscaping job. Davy scooped up her lunch coolers and backpacks, one emblazoned with “Coach” in sparkles on the back, and took off for school.

'So glad you're here'

7:20 a.m. – West Mesa High School sprawls across about 50 acres, with three gyms and numerous buildings connected by wide walkways and horse statues. The mustang is the school's mascot.

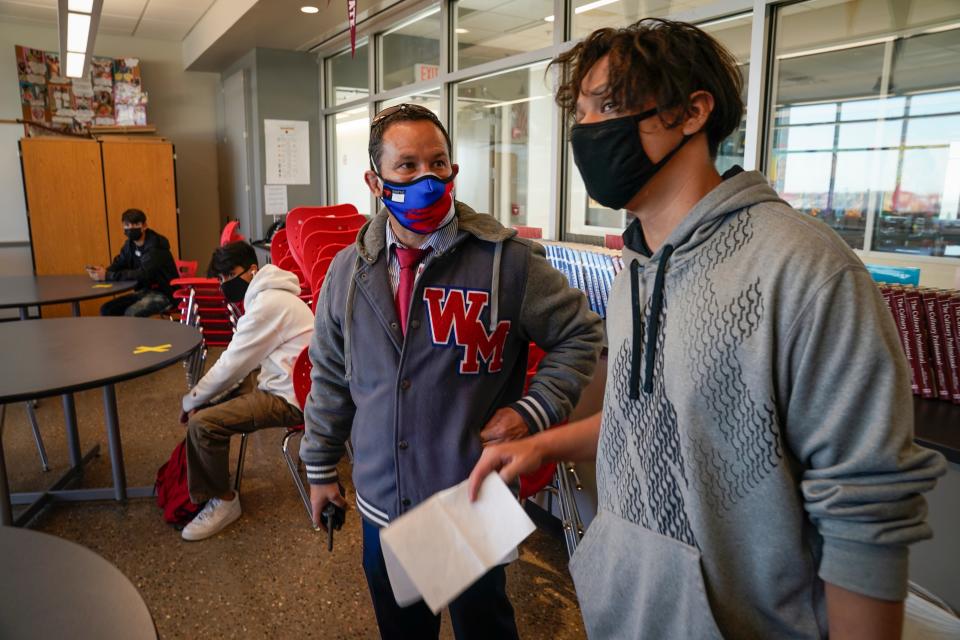

Principal Mark Garcia presided over the arrival of students with an N95 mask covered by another thin mask decorated in West Mesa's colors: red, blue and white.

“We’re so happy you’re here,” he said to the groups of twos and threes that walked in before the final 7:25 bell.

West Mesa is reflective of many large high schools in big cities: Most students are low-income and minority races – Latino, predominantly, in Albuquerque – and academic results are below average. Fewer than 70% of students graduated on time in 2019, district figures show. In other words, West Mesa students were struggling before the pandemic, and remote schooling did not help most of them stay on track or improve.

During the first semester, almost 1 in 3 students posted at least one failing grade, Garcia said. In a normal fall semester, that figure is usually 12%.

Health and economic burdens have further weighed on West Mesa's families. Many students live in multi-generational households where the virus spread freely; the school's ZIP code had one of the highest rates of COVID-19 infections in the city in the fall and winter.

Many parents are service industry workers who saw steep drops in their income, and their children picked up part- or full-time jobs in the past year to chip in, often sacrificing school in the process.

Albuquerque's school board and administration wrestled with reopening plans for months, given the high rate of infections. The teachers union resisted returning out of fear for staff safety. Then the vaccines arrived, and cases dropped.

But a state order to return to in-person instruction by April 5 finally edged Albuquerque, the largest district in New Mexico, out of fully virtual learning. Similar orders from Iowa, Washington and Oregon prompted districts elsewhere to do the same.

As of this week, more than 60% of U.S. students are in public schools offering traditional full-time instruction, according to Burbio, a company that tracks school calendars. That figure has steadily climbed in recent weeks, as the number of all-virtual districts has dropped.

"If it’s safe and we’ve got the vaccines we really need to be getting kids back in school," said Albuquerque Superintendent Scott Elder.

Virtual learning has been harder for almost everybody, he added, and it disproportionately affected kids of color in large districts. Many smaller and wealthier districts, which tend to enroll more white students, returned to in-person instruction months ago.

"These 37 in-person days will be beneficial academically," Elder said. "but it really allows us to build the habits and procedures we'll need for fall."

Missing students, failing grades

7:35 a.m. – As Garcia walked toward his office, a cluster of students hovered outside.

"Do you guys know where you're going?" the principal asked.

That kind of question is usually addressed in August. But dozens of freshmen were only in their second day of navigating the large campus.

A veteran administrator, Garcia has three children of his own. When he worked from school instead of home during the pandemic, he was often alone in the building and found himself longing for the routine of the bell schedule.

“I was a serious student,” he said. “But I’m not sure how I would have handled all this as a teenager myself.”

8 a.m. – Across campus, Davy had unlocked her classroom and made sure the internet was working again. Her room was full of brightly colored chairs, string lights and stickers on the walls.

Her first two hours are scheduled for collaboration and planning, and she scurried out to help one of the school's long-term substitute teachers organize his grading.

'A lot of new rules'

9:25 a.m. – The hallways and classrooms were unusually quiet, given that hundreds of teenagers were back together again. Doors and windows were open, but chatter was muted, even during passing periods.

Part of that is because in-person attendance was low; only 495 of West Mesa's 1,757 students returned initially. Some classrooms had 10 to 12 students, but many had a handful or less. Masks tended to muzzle some of the conversations. And teachers asking questions of at-home learners frequently paused the flow of talk in class.

“There are a lot of new rules,” Elder said, while strolling the building before a meeting.

Garcia noted the hallways were still covered with student work from March 2020.

"It's like a time capsule," he said.

Rane Anaya, a junior in an ROTC class, said it was strange to see her friends' faces covered. Still, new rules like wiping down desks before and after class and standing apart from her peers were better than learning from home, she said.

“I found it difficult to focus and get anything done because of all the distractions."

Such observations underscore the urgency for in-person instruction. But high schools have been the hardest for districts to fully reopen because older children can transmit the virus almost as well as adults, studies show.

As of early April, less than half of U.S. high schools were fully reopened, according to figures from Burbio.

Many high schools, especially in urban districts, are likely to remain closed all year even as K-8 schools in the same communities meet President Joe Biden’s call to return to in-person classes.

Five days a week: Biden recommits to goal for reopening K-8 schools

Lunch is served, outside

10:17 a.m. – West Mesa used to have one long lunch period. Now there are two shorter shifts, held outside, to accommodate distancing.

On Tuesday, workers set up tables to distribute prepackaged burgers, seasoned fries, apples, milk and juice. Students took their masks off to eat, then stood to chat with friends.

Garcia and his top staff gently patrolled the student groups, urging them to scoot a few feet part when they inevitably moved together while talking.

Because the first lunch starts at 10:17, Davy wasn't hungry. She chatted with her colleagues, then went upstairs to unlock the door for the seven students waiting to get into her health class.

10:52 a.m. – The day's lesson centered on a difficult topic: mental health and suicide.

Davy never got to teach this part of the curriculum in 2020. Once school moved online last year and so many students were unaccounted for, Albuquerque decided teachers would not cover new material.

An interactive screen at the front of the room, a Promethean Panel, allowed Davy and the in-person students to see the colorful dots on Google Meet that represented each student logged in from home.

"We need a better name for you guys," Davy called to the dots.

"'Online learners' is too hard to say, and calling you 'at-home students' feels weird. How about 'Skittles'? That's what you guys look like anyway. Like little candies."

Monikers addressed, Davy turned serious. She asked students to jot down what they knew and wanted to know about suicide and mental health. Those in person stuck their questions on the classroom walls; those online typed into a shared document.

Davy sidestepped questions about methods of dying by suicide. She focused on facts and statistics about mental health, played a video, asked students for their thoughts.

One girl offered it was hard when her family dismissed her mental health concerns.

"It gets dark when you're alone with your thoughts," she said.

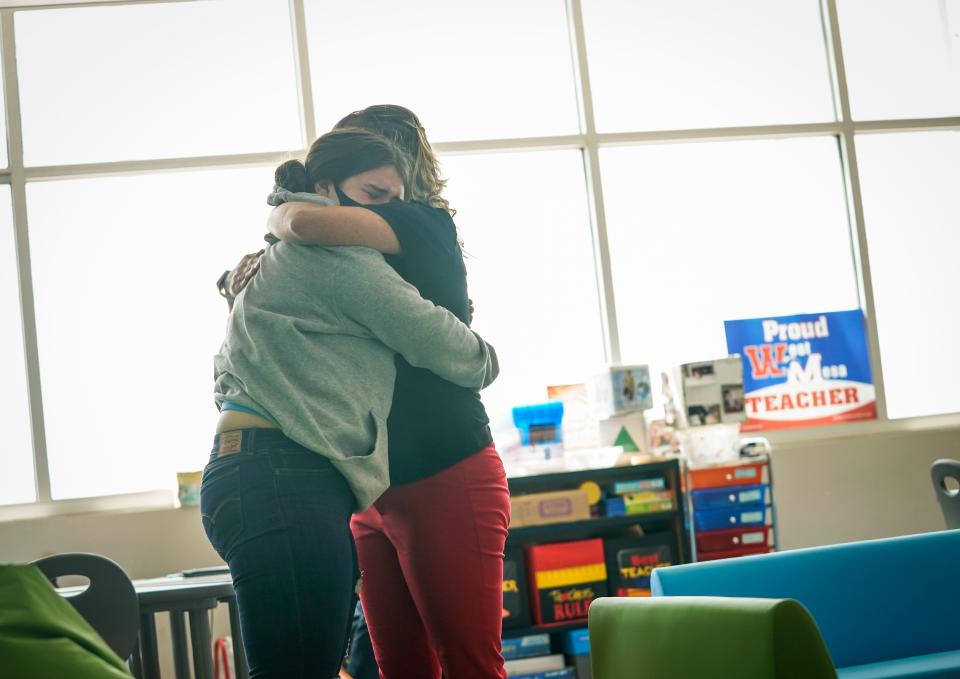

She choked on the last word. A moment later, she starting to cry beneath her mask.

Davy crossed the room and wrapped her arms around the girl.

“Come here,” she said, rubbing her back.

Tough times: Schools are trying to help students crushed by stress and depression

An 'exhausting' first day back

12:42 p.m. – In both her afternoon classes, Davy began by asking students about their first day back.

"I don't know where anything is," said Samuel Chaves, a 15-year-old freshman.

"I finally got to raise my hand in class and talk to my teachers again," said Thomas Roja, 16, a junior.

Several said they found a full in-person school day to be exhausting.

Davy's last class on April 6 is teacher academy, a dual-credit elective for students who might want to become teachers. If they complete all the requirements, they can earn college credit through the high school's partnership with the local community college.

Teacher shortage: Rural schools struggle to keep teachers. Some are growing their own.

In both health and teacher academy, several students arrived who had been on Davy's roster all year but had never attended online. She didn't press them about their long absences.

One new girl in the teacher academy never spoke and completed the day's assignment in silence. Students were to write in-depth responses to how a teacher might handle difficult situations, such as students who continue to fail to turn in assignments.

Davy decided to boost the points associated with the assignment because the grading period was coming to a close. It would help increase the scores of students who hadn't done much all year.

"If they see zeroes, I don't want them to stop coming," she said.

2:40 p.m. – Shortly before the dismissal bell, Davy learned one absent student whose grade had dropped was coming to school for a leadership activity. She texted the activities director to send the girl up to talk.

"Hi – why weren't you in class?" Davy asked when the girl walked into the empty room.

“I’m sorry, I had to work,” the girl said. Davy knew the girl's family was struggling, and she was working extra hours to help them.

But Davy knew the student could lift her grade if she focused. She had missed several previous assignments. If she worked hard, Davy told her, she still had a chance to earn the college credit.

Cheer team preps for state

2:45 p.m. – Davy quickly wiped down her room and sprayed disinfectant while talking by phone with a parent whose daughter abruptly quit the cheer team.

Then she grabbed her bags and headed off to the smallest of the school's three gymnasiums for cheer practice.

The co-ed team resumed practice slightly before school reopened in person, but most of the squad is new. They only have a few weeks to prepare for the May 14 state competition, which was canceled last year.

Davy had a conference call that started at the same time as practice, so she opened her computer, muted herself and blasted the volume while she wrapped ankles and observed toe touches and stunts. The team wore the same colorful school masks. Girls wore matching sparkly hair bows.

Every 10 minutes, per guidance from the state athletics association, the team took a break outside while two assistant coaches sprayed the mats with disinfectant.

5:05 p.m. – "It's after 5, roll 'em up!" Davy shouted.

Students rolled up the thick tumbling mats, then sat in a circle. Davy encouraged them to keep attending school – it would help them continue to make practice.

Then they stood and reached their arms toward the center of the circle for a closing chant.

"One, two, three, MUSTANGS!"

One more duty, then home to family

5:20 p.m. – Davy strode over to West Mesa's largest gym in time to check the books before the 5:30 p.m. girls basketball game against a team from Farmington.

As gym master during basketball in a normal season, Davy oversees ticket sales and monitors the crowd. No fans are currently allowed at games, so Davy makes sure the COVID-19 protocols are being followed.

Once the scorekeeper arrived, she finally relaxed and pulled out her lunch. She'd nibbled only a few carrots and yogurt all day, and she was famished.

6:55 p.m. – Farmington won, and Davy trooped to her SUV for the 20-minute drive home.

"One of the hardest things about teaching remotely was not having that separation between work and home," she said. "I try to do everything work-related at school so that I can come home and just be focused on me and my daughter and my husband."

7:10 p.m. - BrynnLeigh was playing with kinetic sand in front of the television when her mother arrived home.

They greeted each other in the kitchen, and Davy asked Brynn what she did in school. The response was a meandering explanation of amphibian reproduction. Tadpoles and frogs were at the top of the young girl's mind.

"Do frogs get to keep their tails?" Davy asked.

"No," her daughter said. "It's like a little frog, and then it becomes a big frog. And then it goes 'ribbit, ribbit.'"

Brynn decided to eat dinner. Her father, Tyler, looked at Davy and shrugged. "She said she wasn't hungry earlier."

Brynn grabbed a bag of chicken nuggets from the freezer, shook several onto a plate, then pulled out a small stepstool to reach the microwave.

Mother and daughter then resumed their spots at the table, with Davy nibbling fruit and vegetables and Brynn dousing her nuggets in ketchup. They discussed caterpillars and butterflies.

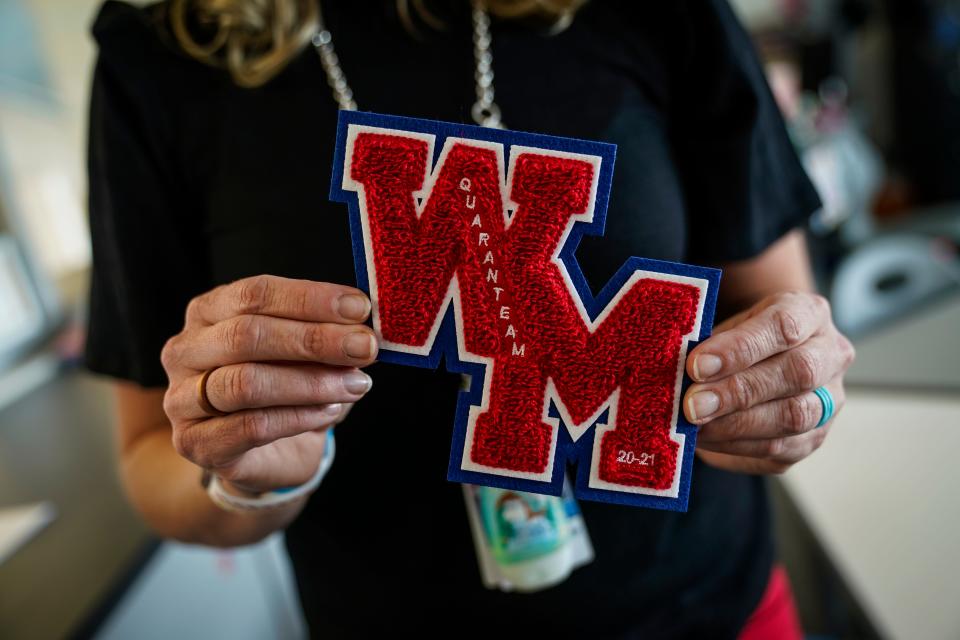

Davy was fatigued from the long day but also energized by her daughter's animated storytelling. The weeks ahead would be challenging – one positive case of COVID-19 at West Mesa five days later would result in a class being quarantined. Attendance for online learners in Davy's class would also dip.

But more students she hadn't seen all year would continue to show up in person.

"They didn't like online school, so they didn't do it," Davy said. "The kids who are coming are the ones who are failing."

She knew she could help them. And she had a few more weeks before summer to try.

Contact Erin Richards at (414) 207-3145 or erin.richards@usatoday.com. Follow her on Twitter at @emrichards.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Back to school after COVID: A New Mexico teacher let us shadow her day

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies