Merrily We Go to Hell: How Dorothy Arzner skewered Hollywood’s happy ending for women in the 1930s

Marriage has long been Hollywood’s happy ending of choice. Some of the most interesting studio films, though, are those that question whether saying “I do” really betokens a lifetime of wedded bliss, or the risk of disappointment and divorce. One of the best of these movies, made when marriage was far more of an expectation than it is today, is Dorothy Arzner’s crisply titled Merrily We Go to Hell, from 1932. It was a box-office hit, and its depiction of wedlock as a trap still has razor-sharp jaws.

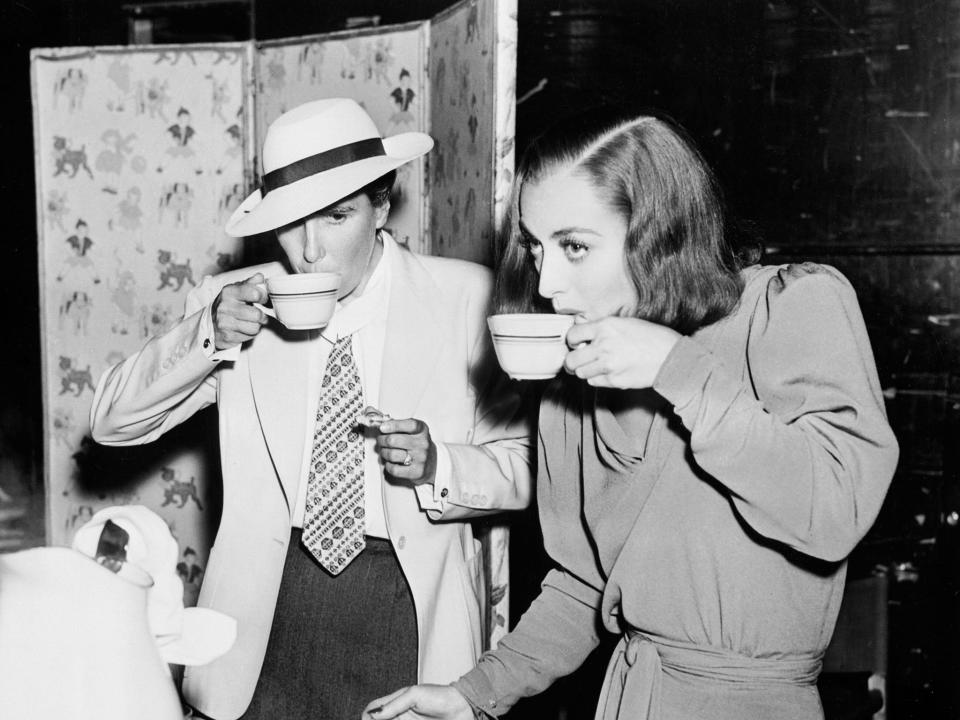

Joan, a doe-eyed debutante (played by the delicate Sylvia Sidney) falls head over heels for Jerry, an alcoholic newspaper hack (Fredric March). Jerry thinks Joan is “swell” and he tells her so all the time, but in truth his heart belongs to the bottle, and his glamorous ex-girlfriend Claire (Adrienne Allen), a blonde actress. The casting is rather inspired. Sydney and March had worked together before and have just enough awkward chemistry to foster hopes for their burgeoning romance.

As the alcoholic Jerry, March exploits his own capacity to portray a split personality, which had recently been unleashed in his Oscar-winning lead performance in Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1931) but here, as in his other performances for director Arzner, he turns in something a little more nuanced, unsettlingly so.

“He has this uncanny ability to be both appealing and off-putting at the same time. He embodies the ambiguity that is central to the film,” says Dr Judith Mayne, professor emerita at Ohio University, who has written extensively on Arzner. “And there’s something very vulnerable about him when he’s drunk.” In 1937, he’d play another notorious, tragic boozer, when he took the role of Norman Maine in the original A Star Is Born movie, opposite Janet Gaynor.

“Merrily we go to Hell” is used as a toast in the film, but also describes how Joan loses her independence, intoxicated by love and Jerry’s intermittent charm. Portents of disaster litter the path to their nuptials: Jerry keeps a picture of Claire on the wall of his apartment and is driven to the engagement party dead drunk, asleep in the backseat. No wonder he muses aloud to a pal, “Have I a right to take a swell girl and make her a wife?” implying the life of a wife is best avoided. The wedding scene is sombre rather than joyful, with hesitant vows punctuated by a painful moment of cringe comedy: Jerry has lost the ring, so he improvises with a corkscrew, which naturally he is never without. The service is officiated by Reverend Neal Dodd, an actor who was also an ordained minister – he “married” hundreds of couples on-screen, and twice as many in real life.

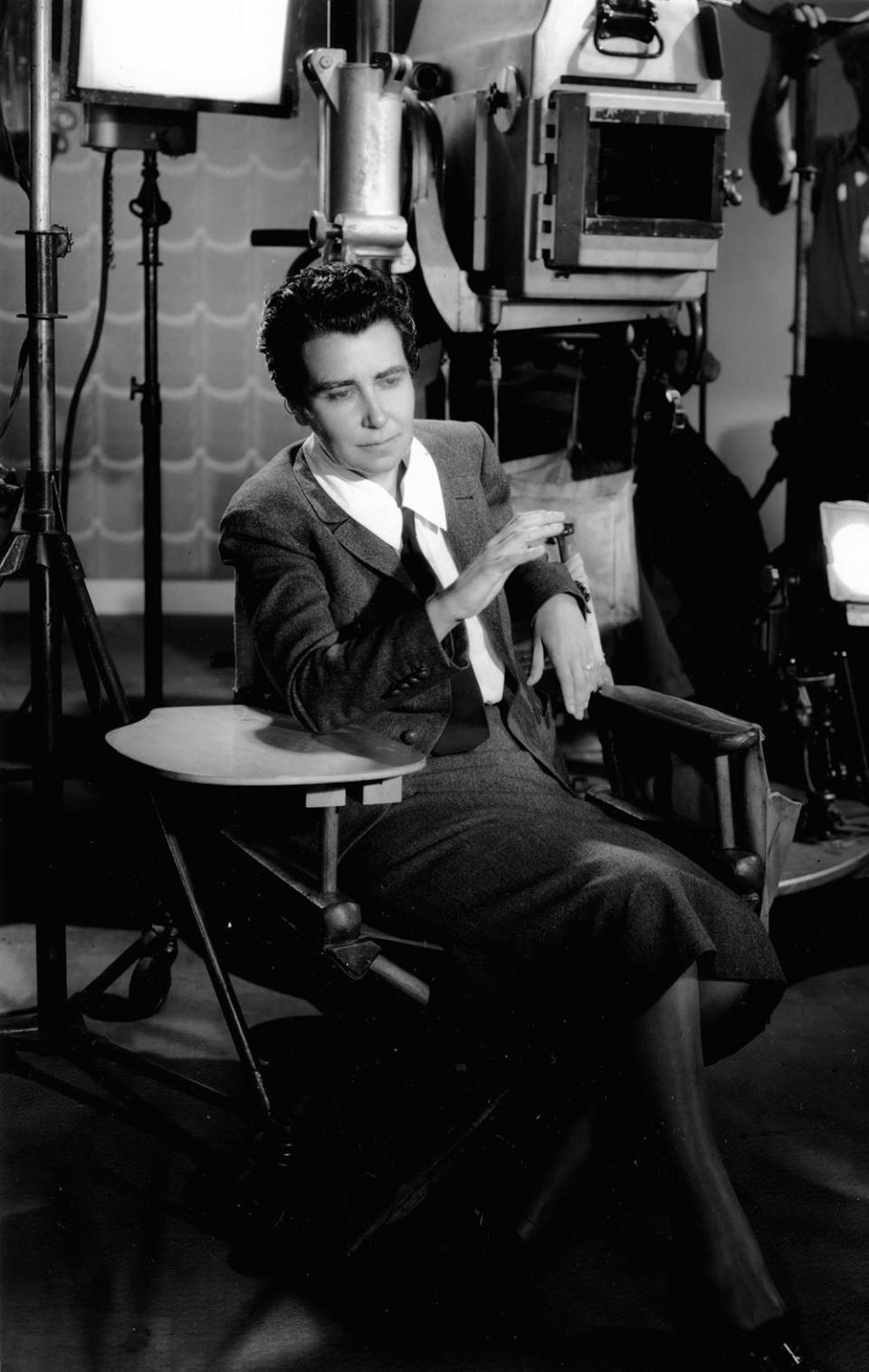

Arzner had plenty to say about the life of women in the films she made, and this was her tenth. She was an independent, queer woman, who lived as openly as Hollywood allowed with her partner, the choreographer Marion Morgan, for four decades. Stealthy critiques of marriage, and society’s expectations of women, run right through her filmography: from Katharine Hepburn declaring herself “shackled” in Christopher Strong (1933), to Rosalind Russell’s mental deterioration in Craig’s Wife (1936). When Jerry is wooing Joan, he sings to her about toothsome morsels: gingerbread, creme de menthe and cake. After they tie the knot, his drunken clumsiness spoils the dinner she has laboured over, and she is forced to serve their guests canned chicken. A bad marriage can leave a sour taste in the mouth.

For Mayne, Merrily is Arzner’s most ambivalent film about marriage, right up to its uncomfortable last scene, which makes a mockery of the idea of a happy ending. “I think sometimes people are very eager to make newer films sound a lot more radical and forward-looking than they are,” says Mayne. “It’s always worth going back into Hollywood history to find what’s really going on in terms of what filmmakers did, frankly what Dorothy Arzner did, in relationship to the current conventions of Hollywood cinema.”

Without giving away a spoiler, the film’s ending is both superficially romantic and deeply tragic. It leaves all the film’s questions about whether marriage has anything to offer women, and Joan’s future, worryingly unresolved.

“If the ending purports to be a conventional restatement of happily ever after, you get the sense that Arzner didn’t quite buy it, so neither do we,” says film critic Helen O’Hara, author of Women Vs Hollywood. And if traditional married life is not the answer to a young girl’s dreams, then neither is breaking the rules. When Joan senses she has lost Jerry’s affections she proposes an open marriage (“Single lives, twin beds, and triple bromides in the morning!”) that is just as hollow as her loveless relationship. Even if she does get to go on a date with a very young Cary Grant, looking very dapper at the very start of his film career. “It still feels a little shocking to see an open marriage in a big Hollywood film today,” says O’Hara, “never mind in 1932.”

As O’Hara points out in her book, the early 1930s were the perfect time to talk about such things, before the enforcement of the Production Code limited what we could see, and what women could do, on screen. It was just a few years before censorship would put an end to movies drenched in booze that condone adultery with Cary Grant. Never mind films with “hell” in the title. “Arzner really took advantage of the pre-Code era to come out pretty strongly against marriage,” says Mayne.

Arzner was defying convention simply by turning up to the set. She was one of the few women working as a film director in Golden Age Hollywood – and the reviews of the film were often distracted by that fact. One critic praised the film for containing “plenty of meat” rather than the “dainty flavor of fudge and cucumber sandwiches [that] hitherto has marked the offerings of Miss Arzner, the industry’s lone woman megaphone wielder. Often her pictures were entertaining, but usually they were self-consciously womanly.” It’s true that Arzner took a different tack to many of her male peers, which worked to her advantage. Her films are particularly strong at telling woman’s stories, and she was known to be a respectful and collaborative director. “Her characters feel far more vivid than some of their contemporaries as a result,” says O’Hara.

She was ingenious too. When silent star Clara Bow had an attack of nerves shooting her first talkie, Arzner whipped up an early boom mic, using a fishing rod, so the actress could speak her lines without worrying where the microphone was. For the time it was made Merrily We Go to Hell features a particularly mobile camera, one that allows us to sway with Jerry’s wobbly gaze when he’s tipsy on cognac, or tracks the couple through their bitter arguments. In an early long shot we see the besotted Joan dancing down the stairs – as joyful, and as vulnerable, as a little girl.

Arzner knew she was good at what she did. Merrily We Go to Hell was the last film she made at Paramount. She left rather than accept a pay cut, and took her chances as a freelancer. She continued directing films until she retired in 1943 for reasons unknown. Many have speculated, though, that sexism, homophobia and the constraints of the Production Code made Hollywood an increasingly hostile place for a woman who craved independence not just for herself, but for her indelible heroines.

‘Merrily We Go to Hell’ is out on Criterion Collection Blu-ray on 14 June

Read More

Marilyn Monroe’s 10 best performances, from Monkey Business to Some Like It Hot

Thelma & Louise: The film that gave women firepower, desire and complex inner lives

Why modern-day romcoms can’t match the zing of Hollywood screwball romances

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies