Meet the ‘Hermettes’: A Secret Society of Women Who Prefer to Be Left Alone

Floating around her “cave” in her indigo linen robe, Risa Mickenberg burns sandalwood incense. Her unruly silver hair stands in stark contrast to the sanctity of her ritual. Computers and phones are nowhere to be seen. The only sound that can be heard is the buzzing of the radiator. Several phone-shaped hunks of wood decorate the table. Stroking the wooden keypad, Mickenberg gives a proud smirk. “Nobody can reach me through this phone as it gets zero reception,” she says. “I feel liberated when I am all alone.”

A creative director at a major advertising agency for over two decades, Mickenberg grew tired of the crazy hours in a corporate environment and left to become a “hermette” after her first solo trip to Maine in 1999.

“Hermette” derives from hermit, and according to Robert Rodriguez, author of The Book of Hermits (2021), hermits are those who live in solitude or in a small social circle. “The society holds many misunderstandings toward hermits,” Rodriguez argues. “People see them as self-centered, anti-social, hostile, cynical, fearful of people, and uncooperative.”

When Mickenberg left advertising, it was not common to live as a hermit, and Rodriguez attests that in the Western world, hermits are still rare. Mickenberg says it’s even harder for women to choose this lifestyle. “The masculine hermit has existed across cultures for many years,” Mickenberg offers. “But the feminine of a hermit—what I call a hermette—is a lifestyle that I believe should become a new feminine ideal.”

Risa Mickenberg's wooden phone

Rodriguez agrees that women need to take greater risks to live in solitude. The modern lady hermits, he explains, are analogous to the Beguines of 12th century Northern Europe—small communities of laywomen with strong religious sentiments who preferred to neither enter convents nor enter marriage. Most took vows of chastity. Their lifestyle, however, was not supported by the public, and the church brought heresy charges against them by the 1500s.

Living alone in Manhattan’s West Village for over five years, Mickenberg says she used to be afraid of living in solitude, and was jealous of friends who had children. The 55-year-old once went to see a therapist and shared her dilemma of whether or not to have children, but when the therapist sympathized with the traditional motherly role, she stormed off. Mickenberg did not want to conform to the social roles imposed on women.

“I think most women are hermits originally, but we’ve been socialized to believe that we have to be devoted to another person,” she reasons, before joking, “I remember thinking to myself just to be a normal person and get married but later I realized that maybe I want to get married just so I can get divorced.”

Mickenberg wishes to change people’s perception of female aloneness. “I definitely think you can have more intimate relationships with more people. A lot of women blame men for their unhappiness. I think taking charge of your own happiness and taking responsibility for it is great.”

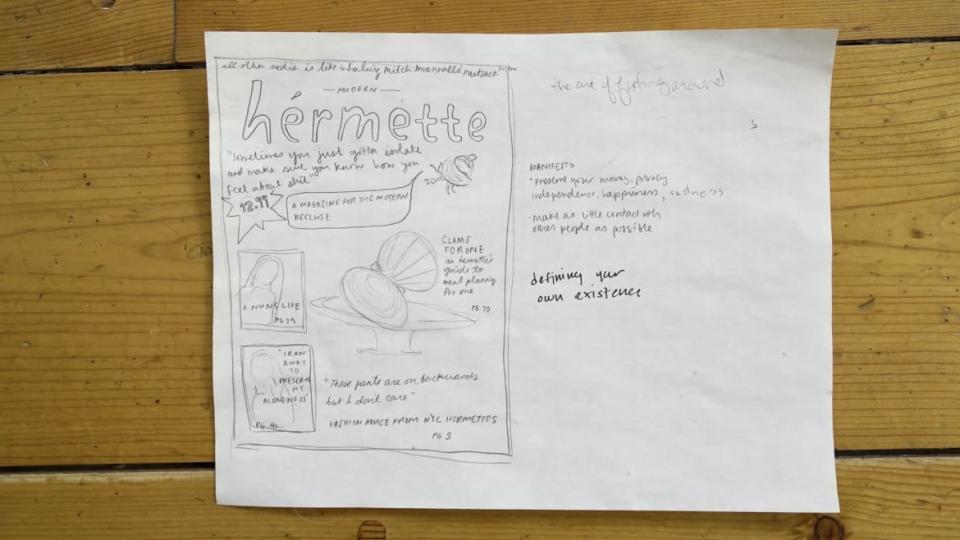

Hermette Magazine's first draft

In 2019, Mickenberg launched Hermette Magazine, a lifestyle “publication” for aspiring lady hermits in New York. The group now has over 30 members all over the world, from Scotland, Germany, Mexico, Greece, and India.

Like the community, the secret society rarely visits the outside world. They get together only when they are really sick of other people and want to fortify their determination to be left alone. “We enjoy the company of others who don’t enjoy others’ company,” says Mickenberg. “We don’t network. By being anti-social, we are being pro-individual.”

Unlike the wilderness hermits who identified with nature, Mickenberg and her fellow hermettes adopted a new way of life in big cities. “Being a hermette in the city means having a version of a cave—some awesome place… your own private retreat—and having the glamor of a self-directed existence in a city where you never feel lonely being alone.”

Rodriguez also points out that hermits living in the city are typically more reclusive and may be artistically inclined, perhaps identifying with the anonymity characterizing the city as a whole.

Penny Arcade, an active hermette in the community and internationally known playwright, agrees: “New York has traditionally been a place of both solitude and sanctuary. This is what people both admire and fear about New York—its merciless anonymity.”

That’s why Mickenberg, the community’s founder, fiercely protects her members’ privacy. “There are ways we recognize each other: eye contact, shopping at The Strand alone, going to Film Forum alone, going to movies at Lincoln Center alone, reading on the subway, looking stylish and comfortable in our own skin,” she shares.

However, the 72-year-old Arcade says the hermette life is not for every woman. Her divorce made her realize she should stop looking to recreate a family unit. She was initially in shock when her ex-husband said he needed autonomy and wanted to end the marriage, but Arcade later realized that she wanted to live alone more than her ex-husband did. It was a liberating gift for her, since she can now enjoy a familial connection and friendship with her ex-husband which is not codependent.

“As opposed to male hermits, there are biological, hormonal elements, and cultural conditioning that make it harder for women to be selfish about their time,” she maintains.

There are economic benefits of living alone as well. “The hermette lifestyle can be wildly satisfying without being expensive,” says Mickenberg. “Our economic system should be designed for the individual. It should reward individuality. Instead, it aims to ensnare you with legal, financial, and social obligations and to engage you in the pursuit of profit and competition.”

Right now, the hermette community still meets up in secret. But Mickenberg relishes when her friends cancel. “I sort of wanted to tell everybody that I really want to be left the hell alone. It’s kind of counterintuitive to wanna talk about it to everyone, but I also don’t want anyone coming to my home. I don’t want anybody here.”

Everyone in the community has a different way of approaching their hermette lifestyle. Across town in the East Village lives fellow hermette Susan Hwang, 49. Her choppy mid-shoulder black hair compliments her black v-neck T-shirt and navy-blue jeans. She completes her look with a crystal necklace and black and white bowling shoes.

Susan Hwang in her apartment

Hwang doesn’t consider herself to be a traditional hermit because she feels it conjures up images of legends and fairy tales like The Hobbit. However, her apartment is what you’d imagine when you meet a hermit. Her black cat, Trout, greets us on the landing of her first-floor walk-up. He acts as a guide, dashing under our feet to lead us into Hwang’s lair. The east-facing windows only give good light early in the morning; the rest of the day is cast in shadow. It’s a neat yet cluttered space, as groups of instruments—accordions, guitars, keyboards, and a drum set—line each corner. At the center of the room, below an altar of knick-knacks bookended by photos of John Lennon and Groucho Marx, is a table covered with a marigold-colored cloth and four tarot decks placed to the side.

Hwang hasn’t always been living alone. In her 20s, she had her “roaring sociable stage.” In college, she met people of different backgrounds, which helped shape her identity. Eventually, this period of social exploration would allow her to find comfort in solitude in her 30s.

“I believe that people in their twenties in general want to, or have a need to, be very social as a part of development as an individual––finding out who you are in a relationship. I feel like as one grows older and into that individual, if one’s natural tendency is toward extroversion, then that person will remain highly social and gravitate toward living situations that feed that,” she says. “Similarly, if in that movement toward yourself, you find that you’re more naturally an introvert, then your life will want to develop along those lines. Since I’m more naturally an introvert, it feeds me to have that time alone.”

Now, Hwang is a musician and energy healer. She’s in a book-themed band called Lusterlit and coordinates musical events around the city. In both careers she welcomes people into her home. She provides tarot and energy readings to guide her clients mentally and emotionally. Meanwhile, she is constantly balancing the social nature of both jobs with her desire to be alone.. “I have to be extroverted,” she says. “And the thing is, I can be. It’s not something that feeds me all the time. It feeds me to an extent.”

Susan Hwang's apartment

The balance Hwang finds between extroversion and introversion rejuvenates her. The time she spends alone feeds her creativity. “I’m a performing musician, so it means that I need some recuperation time after a large event,” she explains. Hwang says it takes her a couple of days after a performance to recharge her social batteries, especially if she hosts the gathering in her apartment.

Despite the misconception that hermits are constantly alone, Hwang still needs community. “I want to feel like I belong someplace. My relationships are some of the most valuable things that I have.”

Nancy Bachman, a therapist in New York who specializes in women's issues, made a distinction that being alone does not equate to loneliness. “I think people need socialization and that’s just who we are as human beings,” she says. “But I also think that if you’re at peace with yourself within your own soul, you can have a very rich life, and that means nurturing yourself with all the things that life has to offer.”

Hermettes are subversive. They toy with societal expectations of women, calling into question the world’s patriarchal systems. Their subculture explores a dimensionality to womanhood that is often overlooked.

Hwang has no interest in becoming a mother. Raised in a Korean-American immigrant family, she faced familial pressure because of her parents’ conservative mindset. Her mom doesn’t approve of her lifestyle because she wants her daughter to have a partner for safety reasons.

Despite her family’s strong objections, Hwang has found her “inner peace,” content with living outside people’s expectations of her. “If you don’t have kids, then they think you’re strange and they may look at you as being selfish,” she says.

Bachman concurs: “I feel like so much of motherhood or even traditional relationships get romanticized. I don’t think that women and mothers talk enough about the struggles and how emotionally depleted they feel, and how they lose themselves.”

But Hwang understands the desire to have children. “If you have a family, then you always have those people to love. You have that role, that context, that structure that keeps you feeling like you belong somewhere. You have societal approval,” she explains, while also weighing the negatives. “The downside is that, you know, kids. I’m just kidding, but what I mean is that you have to deal with all the things about raising another human being. The messiness, and the yelling and the fighting, but that’s also part of the glory.”

Hwang also has a non-traditional view of romantic relationships. She’s been with her partner for five years, but the two do not live together. Her current partner lives elsewhere and visits Hwang during the week. They often spend time cooking dinner, hanging out, and enjoying each other’s company.

Susan Hwang playing the drums in her apartment

Hwang also identifies as bisexual and doesn’t believe in monogamy for herself. She values sex outside of her romantic relationship.

Bachman, too, believes society should embrace the idea of keeping distance between you and your significant other: “I would imagine that living separately and then coming together can be actually quite sexy.”

For Hwang, it’s all about living authentically. “If I’m not fighting my natural tendency, if I’m allowing myself what I require regardless of social expectations, then I’ll live in such a way that others may define me as ‘hermette,’” she says. “I’m doing what feels right and good for me. I believe it’s always better for a woman to feel good.”

When our conversation comes to an end, there’s a momentary pause. For the first time, it’s apparent just how silent it is in Hwang’s apartment. All of the windows are inward-facing, looking onto a shared backyard. It is as though time stands still. The sanctuary of her space shields us from the car horns, emergency sirens, and construction going on outside. We’d left New York without ever really leaving.

Just as we were about to return to the version of the city we knew, Hwang called us back to hers.

“Do you guys want a tarot reading?”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies