McGill pilot projects aims to cool off Montreal with small green spaces

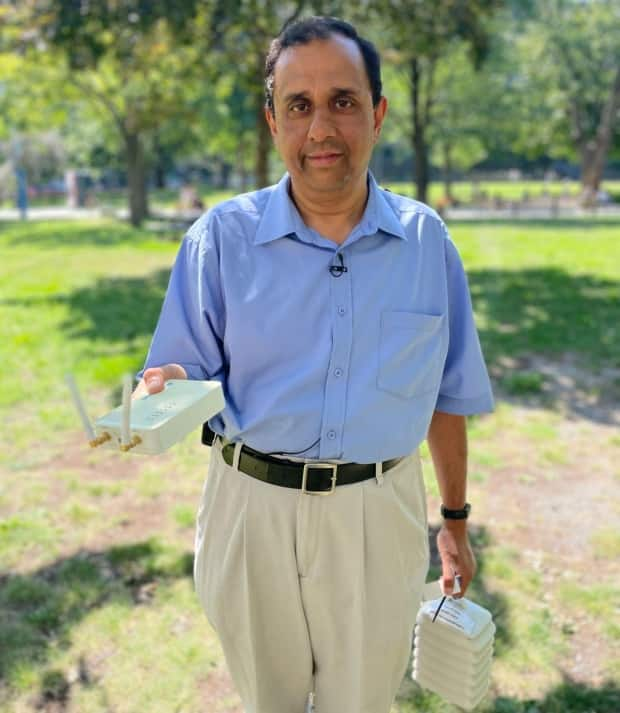

Using a sensor that looks like a white pleated lawn lantern connected to a Wi-Fi router, Raja Sengupta measures the temperature around McGill University's downtown Montreal campus.

It's part of a pilot project to measure the exact impact even a small amount of greenery can have on how hot that space feels.

"We know the urban spaces are warmer than the rural areas surrounding them might be. And with climate change that's getting worse," said Sengupta, an associate professor in the department of geography and the Bieler School of Environmentat at the university .

But he and Alexander Lam, a graduate student, want to find out just how helpful these small spaces are in countering the urban heat island effect.

Recording temperature and humidity in an area throughout the day has long been costly and complicated. The sensors used by Environment Canada, which Sengupta calls the "gold standard," are bulky and cost thousands of dollars.

There are five of those sensors on the Island of Montreal which already show the heart of the city is warmer than its outskirts, despite the presence of spaces like Mont-Royal.

Sengupta is using 40 small, battery-operated sensors that cost about $40 each.

To replicate Environment Canada's methods, the portable sensors are placed 1.3 metres above ground and measure temperature and humidity every 15 minutes. Using long-distance wireless technology, the data is automatically transmitted to researchers' servers.

Researchers hope to get more sensors and expand to the downtown core. They partnered with the Peter McGill Community Council, a non-profit organization and neighbourhood roundtable, to identify more spaces where researchers can place the sensors.

The community group can then use the data to push for more green space in the neighbourhood and acts as the liaison between the researchers and the city.

"We can do the research but we need someone on the ground who can actually make a change," said Sengupta.

Limited, preliminary data from the last year shows sensors placed in small green spaces are up to one degree cooler than those surrounded by concrete.

"(It) doesn't sound like that much but when the weather hits up to 30 degrees, that one degree makes a difference," said Sengupta.

Sengupta noted poorer neighbourhoods are harder hit by the urban heat island effect, making the issue all the more urgent.

"There is what we call an environmental justice issue with urban heat islands," he said.

Maryse Chapdelaine, Peter McGill Community Council's project manager, says most people in her community don't have access to green spaces where they can cool off.

"It's very, very hot. There's so few green spaces, so few parks," she said. "Usually when there's a heat wave, the public service will ask people to go to the mall."

She would like to see more parks, green alleyways and even walls of plants — something she says the community group has been pushing the city to do for a decade.

"But as the time goes on, fewer vacant lots are available," said Chapdelaine.

A spokesperson for the City of Montreal said it acknowledges the importance of green spaces for the well-being of residents and they are "finding innovative ways to green the city" while "ensuring the collaboration of private landowners."

They pointed to the future Sanaaq cultural centre, which the city says will add 1400 sq. m of green space in the area.

"We need those parks, we need those green spaces. So that's why we were very interested in this partnership because for us we can go directly to the elected people," said Chapdelaine.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies