'Mass poisoning crisis': Canadians need to change how we talk about drug deaths, advocates say

There's a poisoning crisis gripping Canada, and it's killing thousands of people each year.

It doesn't involve contaminated meat, lettuce or baby formula – the kinds of safety issues that prompt public concern, product recalls, and holding those responsible to account.

It's a vastly different response to Canada's toxic drug supply, as more and more people – including children – die from what harm reduction specialists say are preventable poisonings.

"If we had poisoned lettuce that was contaminated with listeria or something, they would pull all of that out of the shop, there would be warnings … but because the substances that we use are unregulated, there's not a regulatory response," said Natasha Touesnard, the Halifax-based executive director of the Canadian Association of People Who Use Drugs.

Touesnard is one of many advocates who say Canadians need to change the way we discuss drug use, as an average of 20 people die each day from toxic street drugs. Many of those deaths are the result of drug sellers mixing fentanyl, benzodiazepines or other substances in with drugs like heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine or MDMA to stretch their supply – without giving any warning to customers.

Apparent opioid toxicity deaths in Canada since 2016

Between January and September last year, at least 5,368 Canadians died from "apparent opioid toxicity," which is how the Public Health Agency of Canada classifies substance use deaths involving an opioid.

The number of deaths has soared over the pandemic, as people experienced new isolation, stress and struggles, and as street drugs became increasingly noxious.

But the problem isn't new: since 2016, 26,690 Canadian deaths have been attributed to opioid toxicity.

"It is a mass poisoning crisis that's happening across our country, and the government has the power to fix that," said Touesnard.

Doctors, policy experts, coroners and police forces continue calling for the federal government to enact drug reform that ensures people who use drugs are kept safe, pointing out that models of abstinence and criminal punishment haven't stopped people using drugs – they've only made it more dangerous to do so.

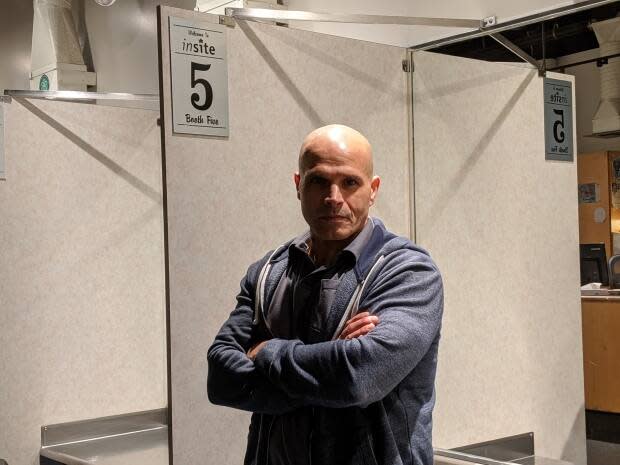

"We have to change, because the drug supply isn't. It's going to increasingly get more potent," said Guy Felicella, a peer clinical advisor for the B.C. Centre on Substance Use in Vancouver.

Changing views on drug use

Advocates say it shouldn't take the deaths of thousands of Canadians for that change to happen – but they're still waiting to see widespread public outrage that will force government action.

"It doesn't seem like there's enough care when people are dying from poisoned supply," said Jonny Mexico, Winnipeg network coordinator for the Manitoba Harm Reduction Network. "I don't know if that starts at the top because politicians don't seem to care, or if it starts with the amount of stigma that is around people who use drugs."

Part of the work involves changing stereotypes about people who use drugs, said Leslie McBain, co-founder of Moms Stop the Harm, a network of families who have lost loved ones due to substance use.

"This is not just those marginalized, vulnerable people. It is our brothers or sisters, our kids."

Some people use drugs for fun, some have a dependency, and some die the very first time they ever try a drug, but "nobody who's using drugs is wanting to die," Mexico said.

That's why, in most cases, the word "overdose" might not accurately reflect why a death occurred. In many cases, the victim took a drug without knowing that fentanyl or another potentially toxic substance was mixed in.

"[Overdose] suggests that if they'd just been more careful, they wouldn't have died, when we know for a fact [that] the market is so toxic right now that there is absolutely no way for people to know what's in the substance that they're buying," said Lisa Lapointe, chief coroner for British Columbia, where more than 9,400 people have died from drug toxicity over the past six years.

In other cases, a person who intended to use fentanyl was unaware they were taking a dose far more concentrated than what they were used to.

"When I'm buying illicit drugs off the street, it doesn't have any of the ingredients. So you tell me what it is – it looks the same to me, I purchase it, I die. That's poisoning," Felicella said.

How to get the poison out of the supply

One solution to the toxic drug supply is to crack down on those who are poisoning it, as happens on rare occasions in Canada. However, harm reduction advocates said arresting individuals isn't the solution to a much larger problem.

"It's the whack-a-mole thing – if you bust ten drug dealers, there's 100 to take their place in two days," McBain said.

"Taking away the market is the way to impact those people and taking away the market means implementing safe supply."

Once again, however, those words – safe supply – mean different things to different people.

The federal government has signalled its willingness to try a medical model, funding a limited number of "safer supply" pilot projects, where people can access prescriptions for pharmaceutical-grade opioids, stimulants and benzodiazepines.

Government of Canada funded safer supply projects

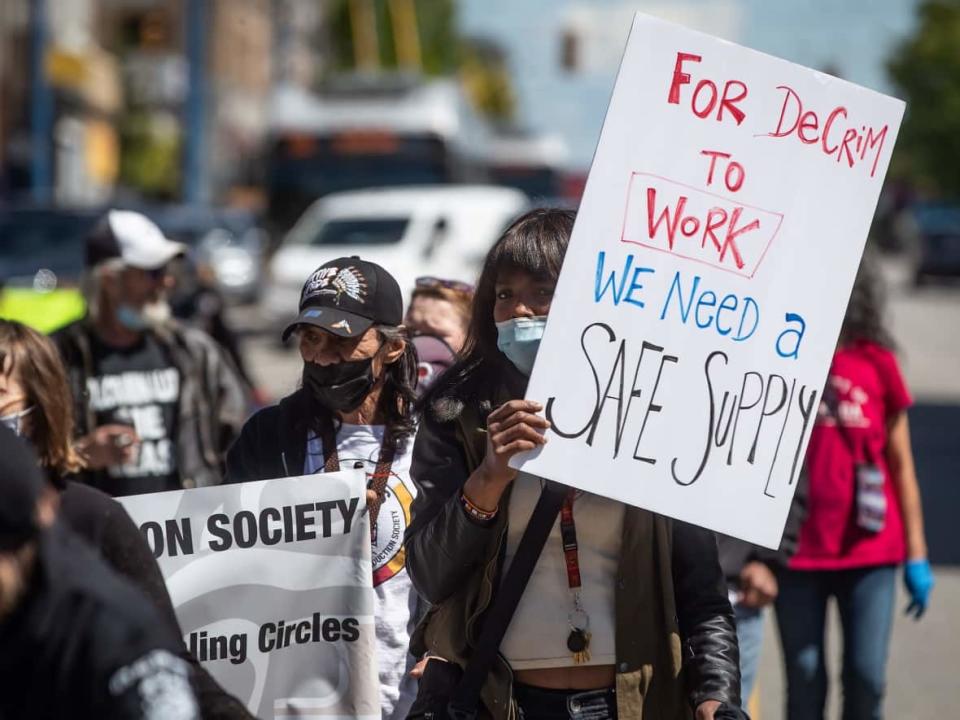

However, many advocates say a bolder model is needed, where drugs are decriminalized or legalized, and regulated in the same way as alcohol or cannabis, to keep people safe and disrupt the toxic drug trade.

As part of that approach, British Columbia, Vancouver and Toronto have all applied for federal exemptions to decriminalize personal possession of small amounts of drugs. The Canadian Association of Police Chiefs has thrown its backing behind the move.

There are also signs of growing public support: in an Angus Reid poll last year, 59 per cent of respondents said they favour decriminalization of all illegal drugs, while the remaining 41 per cent were opposed.

But there is still resistance from other quarters. Alberta's police chiefs said earlier this year that it's too soon to decriminalize drugs, especially without more health supports and treatment services in place.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has also voiced his opposition to decriminalization, saying it wouldn't be the "silver bullet" that advocates suggest.

Lapointe, B.C.'s chief coroner, meanwhile, supports decriminalization and policies to make the drug supply safer. She said there's evidence that drugs can be used safely if the drugs themselves are safe.

"For my office, it's not an ideology. It's very practical," she said.

"We look at what could be done to prevent the deaths, and the only way we are going to prevent the number of deaths we are seeing in our communities is to stop their reliance on the toxic drug supply."

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies