Martin Bangemann, politician who helped to create the Single Market and was happy to take on the UK as he pursued the goal of ‘harmonisation’ – obituary

Martin Bangemann, who has died aged 87, was a former leader of Germany’s Free Democrats who, as a European Commissioner from 1989 to 1999, contributed to the creation of the Single Market, then took charge of the EU’s industrial policy.

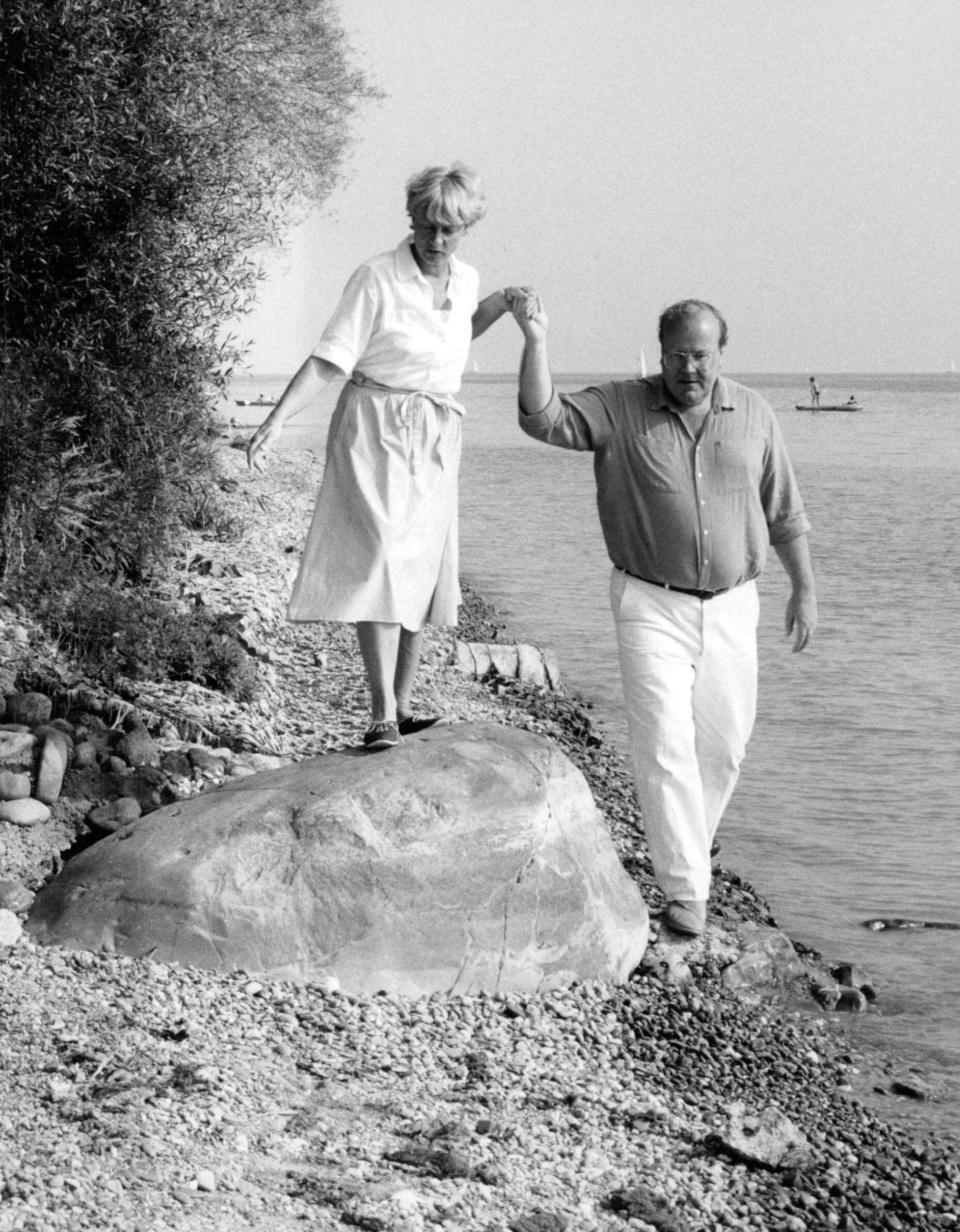

A committed federalist and “passionate liberal”, the corpulent Bangemann offered an easy target to Britain’s Eurosceptics – and to the young Boris Johnson, reporting from Brussels – as he pursued the grail of “harmonisation”.

Bangemann pursued Italy’s rubber industry for making under-sized condoms; proposed harmonising Europe’s gambling industry; and was accused of trying to eliminate the Spanish tilde – the squiggle over the “n” in “España” – from EU documents in the interest of uniformity, and of trying to force through a directive outlawing Britain’s prawn cocktail and barbecue flavour crisps for containing the wrong kind of sweetener.

Nevertheless in battening down the details of the Single Market – something Britain strongly supported – Bangemann took on member governments without fear or favour. He stood up to France over its refusal to classify snails imported from Britain as escargots, and wrote personally to the Prince of Wales refuting his claim that the Commission was trying to outlaw Europe’s smelliest cheeses.

Johnson, who was the Telegraph’s man in Brussels during Bangemann’s first five years, saw him as point man for Jacques Delors’s campaign to impose new burdens on Britain – notably a European company statute making worker participation compulsory. Johnson also reckoned that Bangemann was trying to force member states to put defence procurements out to international tender.

Personally approachable and fluent in five languages, Bangemann bore the barrage of adverse coverage from Britain with a degree of equanimity. He once volunteered to be Brussels correspondent for The Sun, and responded to one BBC interview request: “Do you really want to show your viewers this fat Hun?”

There was, however, far more to him than his 18-stone frame. He was a former economics minister and the first senior German politician to serve on the Commission, and completion of the Single Market was the result of 282 separate initiatives he launched as one of the three commissioners responsible.

He was particularly keen to achieve an open internal market in cars, and an end to states’ import quotas on Japanese vehicles. Bangemann told Europe’s car makers they could hardly expect to sell their products in Japan if trade in the opposite direction was restricted.

His brief stretched well beyond trade. Bangemann’s engagement with the case of the Belgian footballer Jean-Marc Bosman contributed to the eventual ruling by the European Court that clubs could exert no hold over a player once their contract had expired.

Bangemann served six years under Delors as commissioner for the internal market and industrial affairs – three of them as vice-president – and a further four under Jacques Santer, responsible for industrial affairs, information and telecoms.

In this capacity, he blamed Europe’s lack of competitiveness on high labour costs, a lack of innovation, out-of-date infrastructure and inefficient decision-making. But he was unable to persuade white goods manufacturers to agree on a single pan-European plug-and-socket fitting.

He insisted it was member states – notably Britain and Germany – that churned out needless regulations, not the Commission. When Germany’s chancellor Helmut Kohl launched a broadside against Brussels for a “regulatory fury” and “housing an over-powerful bureaucracy”, Bangemann accused him of depicting the Commission as “the big bad wolf of German fairy tales”.

By the latter stages of his time in Brussels, Bangemann was living in style. He spent the weekend at his manor house near Poitiers, with Nelson, his one-eyed cat. With a group of friends he also had a luxurious yacht, Mephisto, built at Gdansk.

Bangemann was notching up 100,000 miles a year in his chauffeur-driven Mercedes, but was found by the EU’s Court of Auditors to have claimed £18,000 in “travel expenses” for speaking at an EU-subsidised business conference in Germany. He insisted the money had gone to Moritz Hunzinger, who ran the Frankfurt PR firm that organised the conference (and was also a partner in building Mephisto).

Controversy erupted when, having had charge of the EU’s relations with the telecoms industry, Bangemann was appointed a board-level adviser to Telefonica of Spain on his retirement in 1999.

Complaints of a “revolving door” brought a reprimand from the Free Democrats and calls from several member states for the European Court to strip him of his pension. The Commission brought the case – the first against a former Commissioner – with Bangemann complaining that he was being subjected to material and moral harm. Telefonica put his start date back by a year, and the case was quietly dropped.

Martin Bangemann was born at Wanzleben, near Magdeburg, on November 15 1934. He read Law at the universities of Tübingen and Munich, earning a doctorate in 1962 with a dissertation titled “Imagery and fiction in law and jurisprudence”. He qualified as an attorney in 1964, practising in Stuttgart and Metzingen until 1979.

Bangemann joined the liberal Free Democrats (FDP) in 1963, won a seat in the Bundestag in 1972, chaired the party in Baden-Württemberg and in 1974 was elected general secretary. He was forced out after a year, having lost an argument about participating in future coalition governments.

Meanwhile, he was appointed to the European Parliament in 1973, holding his seat once direct elections were introduced. He became the FDP’s floor leader at Strasbourg, and from 1979 to 1984 chaired the parliament’s Liberal group.

At the 1984 Euro-elections the FDP lost all its seats, having failed to secure 5 per cent of the vote. Hans-Dietrich Genscher, foreign minister in Kohl’s coalition government, stood down as party leader, and the following February Bangemann was elected in his place.

Despite being a lawyer with no economic experience – and currently out of the Bundestag – Bangemann took over as economics minister from Count Otto Lambsdorff, who was facing trial for taking bribes (he was convicted of a lesser offence and escaped prison).

Confirmed as leader by 332 party delegates out of 394, Bangemann pledged the FDP to stay in coalition with Kohl’s Christian Democrats through the next election, and rebuked Left-wing critics of the arrangement. An economic liberal, he saw the party’s future hinging on acceptance of the free market and promoting technology.

In August 1985 Sonja Lueneberg, Bangemann’s chief secretary for 12 years, went missing; a search of her flat suggested she had been spying. Bangemann hurried back from a visit to the Far East, saying he had no reason to believe this.

Two other officials – including the head of the counter-espionage department, who had tipped off Sonja Lueneberg that she was under suspicion – then defected to East Germany. Police discovered that for 20 years she had been leading a double life, living in Bonn as a hairdresser with a second, false, identity.

In 1986 Bangemann flew to Washington to discuss a technology transfer agreement to involve German firms in President Reagan’s “star wars” initiative. The negotiations were complicated by Germany’s opposition to the US raid on Tripoli.

Bangemann chaired the FDP from 1985 to 1988, and in 1986 regained a seat in the Bundestag. But in May 1988 he resigned the leadership in a bid to succeed Delors as president of the Commission. Delors dug in his heels, and was reappointed after Bonn persuaded Paris to tell him he would not be given a third two-year term (he was). Bangemann joined the Commission anyway, and Lambsdorff became party leader.

One of Bangemann’s last acts as economic minister was to overrule his own party and restructure Germany’s aerospace industry, giving Daimler-Benz a share in the Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm group, in return for continuing state subsidies for Airbus.

Bangemann was appointed one of three commissioners for the Single Market, covering specific industries and the freedom of establishment and services.

An early challenge was a call from Britain’s trade and industry secretary Lord Young to intervene with France, which was refusing to accept UK-built Nissan cars as European because only 70 per cent of its components were made in Europe. Bangemann in turn tackled Young over Britain’s imposition of a 15 per cent ceiling on foreign ownership of Rolls-Royce.

East Germany recognised the EEC in July 1989, and that November Bangemann became the first commissioner to visit the GDR, meeting the chancellor Egon Krenz and his trade ministers. Boris Johnson reported that Bangemann was aiming for a trade agreement with EC’s hidden “13th member”.

While there, Bangemann said East Germany could erupt into bloodshed unless the EEC supported Krenz’s reforms. But community foreign ministers, including Genscher, said a trade agreement would be “premature”. Eight days later, the Berlin Wall came down.

Bangemann urged governments not to impose a false choice between EEC unity and German reunification, and worked up a detailed plan for receiving East Germany into the community; he said the territory should be admitted without having to negotiate a separate treaty of accession.

Bangemann scorned French claims that only a “Yes” vote in their Maastricht Treaty referendum could save the world from a resurgent and aggressive Germany. He sacked his chief of staff Manfred Brunner – who went on to found a Eurosceptic party – for publicly demanding that Germany also hold one.

In November 1992, he joined with Sir Leon Brittan and most of his fellow commissioners in a showdown with Delors over his efforts to wreck the GATT world trade negotiations at the behest of Paris.

In Delors’s revamped Commission, Bangemann prioritised restructuring Europe’s steel industries and reducing their capacity. Initial talks collapsed when Italy refused to make cuts, but in February 1994 he persuaded state-owned steelmakers in Germany, Italy, Portugal and Spain to cut production by 5.5 million tonnes – 10 per cent of surplus total capacity.

Bangemann led a high-level group that in 1994 produced the report Europe and the Global Information Society, which declared that “nobody can hold up” the process of opening up national telecoms monopolies to competition. In Santer’s Commission, he challenged the IT industry to develop high-speed networks across Europe.

Martin Bangemann married Renate Bauer in 1962. They had three sons and two daughters.

Martin Bangemann, born November 15 1934, died June 28 2022

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies