Made in Miami: How a South Florida plot to oust Haiti’s Jovenel Moïse led to his murder

Scroll to Continue

Editor's note: Viewing this story in our app? Click here for a better experience on our website.

There is a saying: “In the heart of every Haitian, there’s a sleeping president.”

Haitian authorities say that was certainly true of Christian Emmanuel Sanon, the man some already called “President.” And he had devotees in South Florida — and Haiti — willing to help him achieve his vision.

Sanon, a Haitian-American preacher and physician who split his time between Florida and his homeland, became the central character around whom coalesced a plan to topple Haitian President Jovenel Moïse and install him, Sanon, as leader. He held meetings in Port-au-Prince and at the Tower Club in downtown Fort Lauderdale in early May 2021 with associates to go over an ambitious redevelopment program to “save Haiti.” No hard evidence has been presented in support of the insistence by Haitian police that his plan, his goal, involved an assassination.

But over several months, a sprawling array of characters became entangled in a complex plot to get rid of Moïse. Among them: an ambitious Haitian Supreme Court justice, a convicted drug trafficker, an ousted Haitian corruption fighter, a well-known politician, former and current cops, an ex-Drug Enforcement Administration informant and a current FBI informant, two Doral, Florida-based security firms, and former Colombian fighters turned soldiers of fortune.

Amid disparate motives and seething grudges, mission creep set in and the coup evolved into an assassination. U.S. investigators, who are conducting a probe parallel to those in Haiti and Colombia, say it followed the failure of a precursor scheme to kidnap Moïse on June 19, 2021. The murder was carried out in bloody fashion in the early morning hours of July 7, 2021.

As the killers fled, leaving behind a president both tortured and shot 12 times, they are believed to have hauled away a huge stash of money, somehow amassed by Moïse while serving his Caribbean nation of nearly 12 million.

Three men currently jailed in Miami — two Haitians and a Colombian — are facing trial here in the spring. Their federal prosecutions could cast an intriguing light on the anatomy of the assassination. In Haiti, meanwhile, a trio of Haitian Americans with ties to South Florida are being held, among more than 40 people who have been arrested there, while still others remain on the lam.

The following is believed to be the most comprehensive published accounting to date of Jovenel Moïse’s murder and the mystery surrounding it — including how it wasn’t supposed to be a murder at all. It is based on interviews, a 124-page Haitian police report, phone records and three U.S. indictments.

Chapter 1

A South Florida Plot

A plan and a promise

The mission that led to the assassination of Moïse in a politically volatile Haiti involved a cast of shadowy characters connected in some way to Christian Emmanuel Sanon, 64, a fixture for more than two decades in South Florida, where he once filed for bankruptcy. His bogus claims of U.S. government backing were among many lies.

There is James Solages, 37, a maintenance director who quit his job in April 2021 at a ritzy Lantana, Florida-area senior-living center to work for one of the Doral security firms aligned with Sanon’s efforts.

Solages, who had signed up with Counter Terrorist Unit Security, or CTU, told people the company had a contract with the U.S. Embassy in Port-au-Prince looking into the issuance of visas. It was a lie.

Then there is Joseph Vincent, 57, an ex-DEA informant and like Solages a Haitian American. He was once arrested and charged with filing false information on a U.S. passport application. Moving to Haiti seven months before the attack, he was in contact with several suspects, including police officers accused of driving Colombian commandos to the president’s house on the night of July 7.

Phone records examined by the Miami Herald show Vincent’s phone making calls to the offices of House Foreign Affairs Chairman Gregory Meeks, D-N.J., and member Andy Levin, D-Mich., as the plotting unfolded. The two representatives were among a group of U.S. lawmakers calling for Moïse’s removal from office. Aides to Meeks and Levin say they have no records of any communication.

“Our office does not have a record of a call because no one left a voicemail. However, we were made aware by an outside party that a call by Mr. Vincent was made,” the aide to Levin said.

And then there is Sanon himself. Months before the assassination, he sought to hire individuals with military experience through CTU to safeguard him in Haiti at a monthly rate of between $2,700 and $3,000 per commando. A letter dated May 29, 2021, was sent to the State Department urging U.S. support for him to preside over a three-year transition in Haiti.

Among the signatures on the letter was that of the head of AYITI2054, a political party connected to Sanon, and Port-au-Prince lawyer Phénil Gordon Désir. Désir, Haitian police say, was in regular contact with Vincent and other suspects up until the killing. He has not been arrested, although a warrant for his arrest in connection to the assassination has been issued in Haiti.

The same month the State Department letter was sent, Sanon chaired the downtown Fort Lauderdale meeting, billing it as a Haiti development discussion. It took place at the Tower Club, a hub of the city’s business elite, and is a key milepost in the Haitian police investigation. Attendees included several of those who are either currently wanted by police, already in custody or have been questioned as part of the parallel U.S. investigation.

Among those present: Antonio “Tony” Intriago, a Venezuelan émigré and the owner of CTU Security. He was introduced to Sanon by Solages. Intriago worked alongside his business partner, Arcángel Pretel Ortiz, to find Sanon his Colombian bodyguards. Pretel operated CTU Federal Academy LLC, a firm affiliated with Intriago’s similarly named security company. He tapped a closed WhatsApp group of former Colombian soldiers to hire for the Haiti mission, a Colombian source who is part of the WhatsApp group said. Pretel relayed his progress to Sanon and Solages in video meetings, where his name appeared as Gabriel Pérez.

A Colombian national like the ex-soldiers he recruited, Pretel once testified in a cartel case as an FBI informant and was still working for the agency at the time of the assassination, several sources told the Herald. He has not been arrested.

Intriago also brought in Walter Veintemilla of Miramar-based Worldwide Capital Lending Group to help Sanon with financing.

The plan, said a Veintemilla lawyer, was for Worldwide to provide Sanon with a loan to be used by Intriago to help with the cost of security. The money would be repaid with Haitian assets secured after Sanon became president by what the lawyer described as “a peaceful transition of power.”

Through their lawyers, Veintemilla and Intriago both deny any involvement in the assassination. Neither has been arrested, although their offices have been searched by the FBI and Homeland Security Investigations agents. Pretel has kept a low profile since the assassination, and he is likely staying in South Florida. The source in the WhatsApp group says Pretel, by virtue of his background, was able to convince recruits that the U.S. government was in on the recruitment effort. There is no evidence that he was operating under the direction of the FBI.

The former Colombian soldiers arrived in Port-au-Prince on June 6, 2021, from Bogotá via Santo Domingo in the neighboring Dominican Republic. They were greeted by Sanon, who had disembarked days earlier from a private jet, and Ashkard Pierre, a friend of the pastor, who is also the subject of a wanted poster, in connection to the assassination, issued by Haitian police.

After the Colombians’ arrival, some of the Haiti suspects who joined forces with the Colombians worked to secure arms by contacting local gang leaders. The initial plan was to “capture” Moïse at the Port-au-Prince international airport with the help of the Colombians and spirit him away by plane.

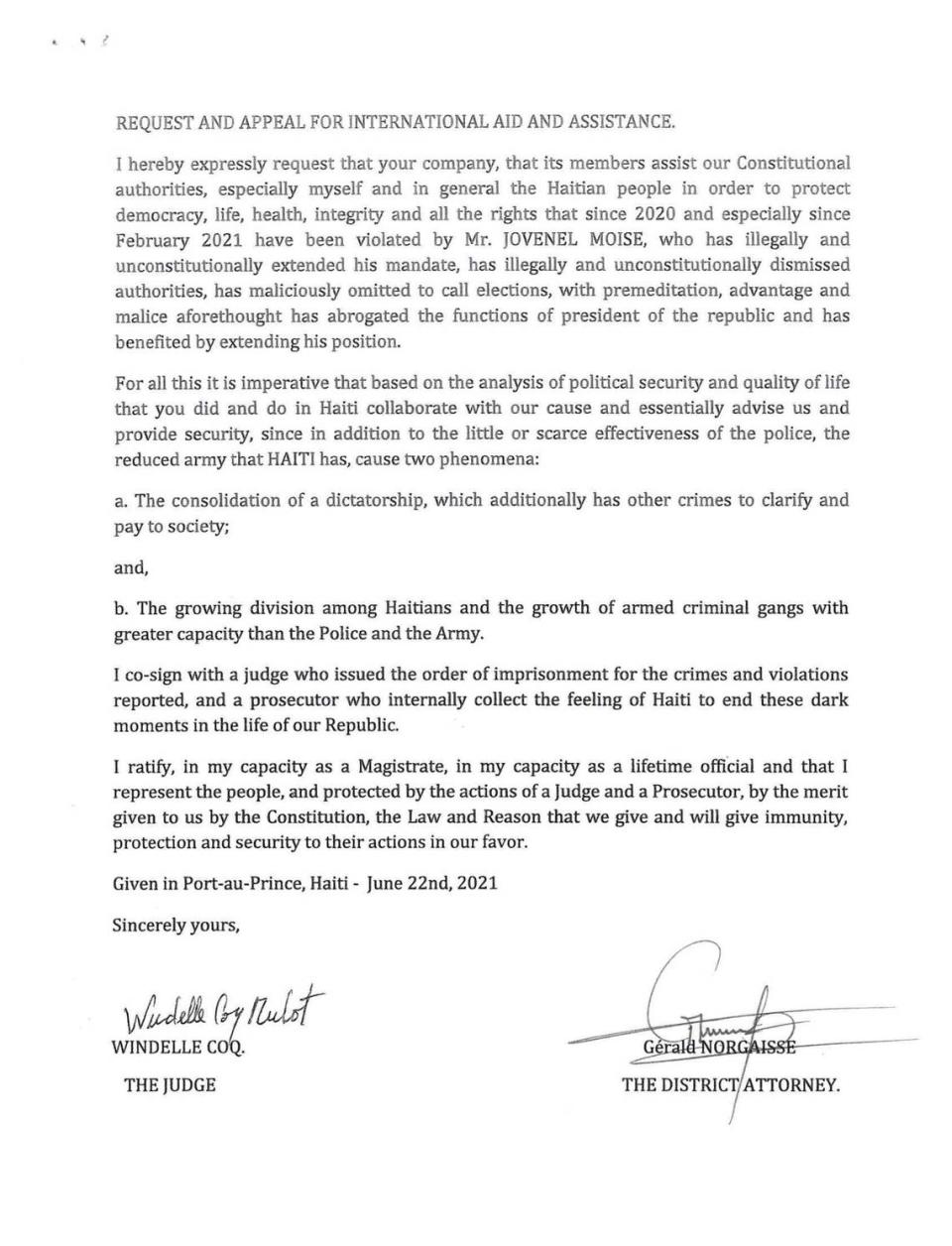

Moïse, who returned from an official overseas trip to Turkey accompanied by his wife and others, was unaware of what awaited on his return to Haiti on June 19, 2021. The plan was aborted when the getaway plane never arrived. Less than 10 days later, on June 28, Solages traveled back to South Florida from Haiti bearing a letter dated June 22, requesting assistance from Intriago, and promising “immunity, protection and security.”

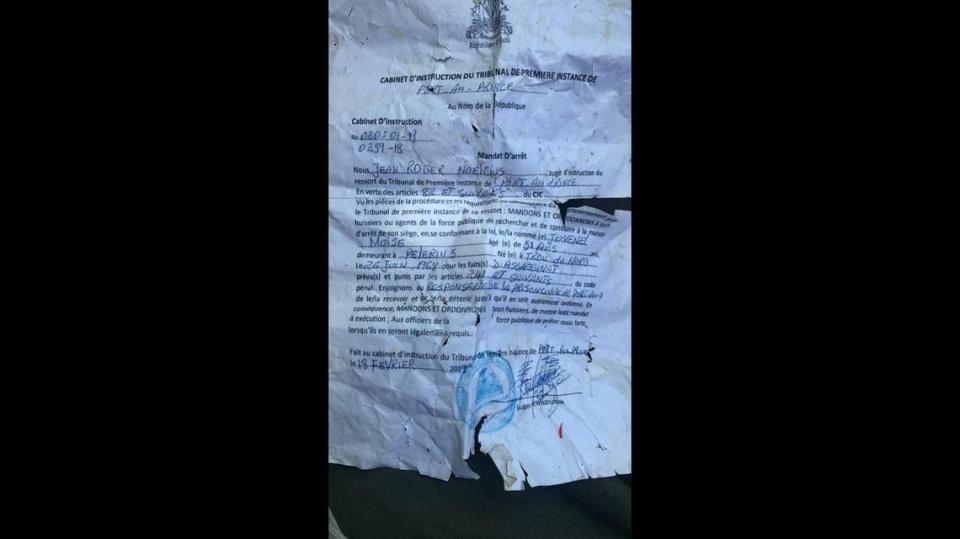

The letter bears a signature of Haiti Supreme Court Justice Windelle Coq Thélot and District Attorney Gerald Norgaisse, who previously told the Herald the signature was not his. Haitian authorities believe the signature of Thélot is valid although she has also denied its authenticity. Moïse had fired Thélot — illegally — months earlier after her name emerged as a potential presidential successor following an alleged Feb. 7 coup attempt. Thélot was known as “Diamante” or Diamond to the commandos who would take part in the plot, according to Colombian and Haitian investigators.

Along with Sanon, Thélot was in the running to replace Moïse in the event of his ouster, though she has denied involvement with any of the plotting. The prosecutor’s office in Port-au-Prince has issued an arrest warrant for her in connection with the assassination while Haitian police have issued a wanted poster. U.S. investigators say in a criminal complaint that by the time Solages handed over the letter during his return trip to Florida, certain plotters had knowledge — or at least believed — that the plan was no longer to kidnap the president but to kill him.

U.S. prosecutors say that trip by Solages, who is referred to as “co-conspirator #1” in the U.S. criminal case and returned to Haiti six days before the deadly attack, is a key figure in their investigation because it highlights that part of the plot that led to Moïse’s death was hatched in South Florida.

Chapter 2

The Assassination

‘The President is dead’

“Get ready,” the caller told retired Colombian Sgt. Edwin Blanquicet Rodríguez.

It was to tell him to prepare. A police officer was on the way to pick him up and escort him to where the other commandos were waiting. The mission was a go. Ultimate destination: Pèlerin 5, the neighborhood overlooking Port-au-Prince where Moïse had his personal compound in a rented multi-story house.

It had become a sort of de facto presidential palace since the official residence, the two-story French Renaissance-inspired National Palace, crumbled in the 2010 earthquake. Since then, temporary presidential offices have been at the old Casernes Dessalines, the former army barracks, which doubled as a cell block for political prisoners, who were once sent there to be tortured or killed.

Moïse had stopped going to the palace about two weeks before his death, suggesting that he feared for his life, said several sources, including the National Human Rights Defense Network, which undertook an investigation into the attack.

Blanquicet was with Sanon along with other former Colombian soldiers in the Delmas 60 neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, where Sanon now lived and held political meetings at a private home belonging to a Miami-based businessman and real estate developer. The would-be president had been kicked out of a local hotel for nonpayment. They had just finished watching Colombia lose to Argentina in the 9 p.m. soccer match when the instructions came from the caller, identified by Blanquicet only as “the boss.”

Across town, Joseph Vincent was in the Laboule 23 neighborhood when his phone rang. He was at a home controlled by businessman and convicted cocaine trafficker Rodolphe ‘‘Dòdòf” Jaar. Like Vincent, he also was a former DEA informant.

Vincent’s caller was Joseph Félix Badio, who had been fired from the government’s anti-corruption unit in May. Vincent later told a Haitian judge that Badio called to say Moïse was home watching soccer. For months, Badio had been spying on the president, aided by turncoat agents in Moïse’s security detail.

Also monitoring the president’s comings and goings was Marie Jude Gilbert Dragon. Dragon was a soft-spoken former police commissioner and one-time rebel leader who had helped oust an earlier president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, in a bloody 2004 coup. Dragon kept tabs on Moïse’s whereabouts through one of his former cops working as Moïse’s backup driver, Jude Laurent.

Laurent is accused, in a judge’s report, of leaving the oversized iron gates to Moïse’s front yard wide open after informing Dragon of the president’s presence inside.

Dragon and Badio would speak at least three times between 9 p.m. and 9:42 p.m. on July 6, the day before the assassination, according to phone records.

Those records show Badio to be in the hills of neighboring Thomassin 31 and 38, minutes away from Moïse’s home. Also in Thomassin were the drug trafficker Jaar, and James Solages, who by then had been joined by fellow Floridian Vincent, according to calls traced back to their phones.

Jaar, now in U.S. custody awaiting trial, would later admit to distributing firearms and ammunition and harboring some of the Colombians prior to the assassination.

The operation got under way in earnest sometime after 12:42 a.m. July 7 as Vincent and Solages jumped in a vehicle with two of the Colombians. In front of them was another vehicle carrying two more Colombians and two Haitian police officers. All were headed down the two-lane blacktop mountain road from Thomassin to Moïse’s residence in Pèlerin 5.

Breaching at least three security checkpoints with little resistance, the two vehicles approached the walled-off compound. The vehicles were bristling with assault rifles and ammunition and had clothing tags bearing the letters “DEA.” The bogus tags were supposedly fashioned by the former police commissioner, Dragon.

The four commandos with Solages and Vincent were a small part of a Colombian contingent that numbered 22 in all. They were divided into teams. Key among them was the five-man Delta penetration team, which was by then aware of the assassination plan, according to investigators. Its task was to force its way into the president’s second-floor bedroom.

At about 1 a.m., shots were fired outside the compound. Moïse’s 24-year-old daughter, Jomarlie, ran to the room of her younger brother, Jovenel Jr. The two hid in his bathroom.

“This is a operation. This is a operation. DEA. Everybody go go go,” Sanon’s South Florida associate Solages yelled in English through a megaphone, standing alongside Vincent in the middle of the dimly lit street. Then in Creole, Solages warned everyone to get down and said “Pa tire!” — don’t shoot.

Grenades dropped from assault drones. A gun battle erupted between the Colombians and the president’s security, but Moïse’s detail didn’t put up much of a fight. Officers eventually retreated, allowing the attackers to shoot their way in.

Upstairs in his bedroom, Moïse was in a panic as the armed mercenaries peppered his front door and walls to gain access. His conference room would be ransacked. Also his bedroom.

Phone records of Badio, the ousted anti-corruption official, show his calls pinging the same cell towers as Moïse’s frantic pleas for help. If Badio wasn’t in the house, he was at least on the scene.

Among the people he was in contact with: Cinéus Francis Alexis.

Reportedly close to Supreme Court Justice Coq Thélot, Alexis had kept in frequent contact with Rodolphe Jaar, the convicted cocaine trafficker, and ex-Sen. John Joël Joseph. Both Jaar and Joseph are accused of providing vehicles and weapons to the Colombians in advance of the hit, while Jaar also admitted to housing them. On this night, though, Alexis’ contact was Joseph Félix Badio, leading police to describe Alexis in their report as “an interlocutor” — a go-between — in the plot and Badio as a leading suspect.

The two men spoke more than a dozen times on July 6 and 7, including at least four calls in a span of 25 minutes during the assault. As the calls occurred, Alexis was driving from the well-to-do suburb of Pétionville, passing the landmark Hexagon building that houses the Brazilian Embassy, en route to the presidential palace. He arrived around 2:29 a.m., reportedly with the intention of installing Moïse’s eventual replacement.

By the time the Colombian Blanquicet arrived at Moïse’s residence in a seven-car motorcade driven by Haitian police officers, Moïse’s guards were gone. Blanquicet said he saw gunshot flashes coming from a room on the second floor, and four men fleeing through a back door.

One Colombian who entered the house claimed he had found the president already shot and yelled: “The president is dead! The president is dead! Let’s get out of here! They laid a trap for us!”

Colombian squad leader German Alejandro Rivera Garcia, aka “Col. Mike,” emerged from inside the house.

Rivera took out his phone in front of Vincent and Solages. They saw a digital image of the president’s corpse. Rivera made a call. “The president is dead,” he reported.

Chapter 3

The Aftermath

Missing Millions and Surveillance Cameras

“We are free now,” Martine Moïse, the president’s wife, said to her children when officers responding to her husband’s calls for help arrived and she recognized one of them.

Jomarlie and her brother had emerged from their hiding place. They had found their mother sitting near the stairs, in a blue T-shirt and floral skirt. Blood dripped down her right arm. She had been shot.

Bullet casings were everywhere. The surveillance cameras had been torn out and bags of cash known to be at the president’s home were missing.

Several sources told the Miami Herald that the amount of stolen money was potentially in the tens of millions of U.S. dollars, but that figure has been disputed, at least by U.S. investigators. The former soldiers, who struggled to collect their promised pay during their time in Haiti, were supposed to take a cut of Moïse’s money and the rest was to go to the Haitian plotters. The Haitians were supposed to be part of a new government, a source with knowledge of the Colombian investigation told the Herald, based on statements from Colombians in custody in Haiti.

In an otherwise detailed 124-page investigative report, Haiti National Police say only the attackers “stole large sums” along with the surveillance system. No further precision has been provided by police, except that the cash was hauled away in duffle bags, according to some of the Colombians interviewed.

The money haul has raised a red flag for some Haiti observers who wonder why a president would have such large quantities of money stashed at his home, how he could have acquired it and specifically whether it could have been the fruits of narco-trafficking or other illegal activities. But several U.S. law enforcement sources say they’re not looking into drug-trafficking or the money as part of the probe.

Turmoil, Arrests and Questions

“Everyone get back in your cars. We need to leave now,” the Haiti National Police inspector screamed.

The high-ranking Haitian officer had received the frantic call for help from the president. Before he could ask questions, he heard through the phone the assault rifle go off.

Yelling out orders to his fellow officers, he turned out of the parking lot of the police headquarters and headed toward Pèlerin 5.

By the time they arrived in a three-car police convoy, there were other officers on the road. Dimitri Hérard, the head of General Security Unit of the National Palace (USGPN), who had been called by both Moïse and security coordinator Jean Laguel Civil, was standing in the middle of the main road leading to the turnoff to Moïse’s residence.

Hérard, who had been put in the palace by the previous president, Michel Martelly, had made frequent trips to Colombia prior to the assassination. He, along with Civil, had been tasked by Moïse with investigating the alleged February 2021 coup attempt.

Hérard saw the speeding cars coming up the hill and pulled out his weapon. Recognizing the officer in the lead vehicle, Hérard lowered his gun.

While Hérard’s officers were the first line against an assault by assassins, the final layer of protection was the Presidential Security Unit. Seven of the police officers assigned to protect Moïse that night were members of the unit and were, along with the USGPN, supposed to save the president in the event of an attack. Hérard’s location and behavior that night aroused suspicion among the responding officers.

As Hérard and his camouflaged team stayed in the middle of the road, the police inspector called by Moïse moved with other officers to try and block anyone from exiting the neighborhood as one of the police vehicles attempted to reach the front gate.

As that vehicle advanced toward the compound, some of the commandos, dressed in white T-shirts and armed with assault rifles and carrying military backpacks, pointed guns at the police.

Officers behind an unmarked police SUV tried to advance on foot. Hérard approached and told them to back off. Hérard is currently in jail in connection with the assassination.

The police inspector, in an unmarked car, shifted into reverse, heading back down the hill to the intersection with the main road. After a standoff between police and commandos, the Colombians retreated, allowing the inspector to get to the front door. It was too late.

The inspector found the wounded Martine Moïse. Her husband was sprawled in a pool of blood. Eventually, more officers arrived, followed by a justice of the peace to document the haunting scene: drawers pulled out, walls riddled with bullet holes, bullet casings carpeting the floor.

The Colombians and the two Haitian Americans, Solages and Vincent, were by then on the run. Also gone was Badio, the fired former government official. Phone records show Badio got in touch with John Joël Joseph, the former senator whose name is also written as Joseph Joël John.

Later that same morning, Badio would call Ariel Henry, the prime minister-designate, whose nomination for that post had quietly been made months before but had become public only two days prior. Badio, once under consideration by Moïse for interior minister, would place two calls totaling seven minutes to Henry hours after the assassination. Henry would later say he didn’t recall speaking to Badio.

The predawn attack threatened to plunge Haiti deeper into turmoil. It fanned fears of more political gridlock and violence as anger erupted in a population that felt violated. Questions lingered and still do: How did someone manage to get past the president’s security checkpoints, including three layers of protection? Who did this? Why?

Claude Joseph, the foreign minister and acting prime minister at that time, declared a state of siege and imposed martial law. International airports were shut and the usually porous border with the Dominican Republic sealed.

Vincent and Solages, the men who along with Sanon had Florida ties, eventually surrendered after freeing police officers they held as hostages. Sanon’s whereabouts during the assault are not known, but he was later arrested. Other suspects tried to hide in a two-story building just off the highway in Pèlerin 2. After police tracked them down, a bloody gun battle ensued. A white pickup burst into flames. Duberney Capador Giraldo, described by a Colombian source as the leader of the commandos, was killed, along with two other alleged members of the hit squad.

Eleven of the Colombians would seek refuge at the nearby Taiwanese Embassy, only to end up under arrest. Two days after the killing, Blanquicet was among others captured. They were hog-tied and placed in the back of a pickup truck by an angry mob in the Jalousie slum.

A crowd gathered in front of the Pétionville police station to demand: “Burn them!”

Today, there are 42 suspects imprisoned in Haiti, including 18 Colombians, the three Haitian Americans and various Haiti National Police officers who were tasked with protecting the president.

Dragon, the former police commissioner who had spied on Moïse and who turned himself in for questioning after the assassination, died four months later in custody. COVID-19-related illness was blamed.

Still on the lam are Badio, the fired corruption fighter, and the one they called “Diamante”: Supreme Court Justice Windelle Coq Thélot.

Who Killed Moïse?

U.S. investigators are building the Haitian president’s assassination case around a circle of players, correspondence and circumstances that point to an alleged murder conspiracy with roots in South Florida, Haiti and possibly other countries, according to court records.

In the latest two-count indictment filed in October, the three defendants held in Miami are charged with “providing material support or resources” between June 2021 and July 7, 2021, to carry out a “conspiracy to kill or kidnap” the president of Haiti. All three have pleaded not guilty and are scheduled for trial in late March in Miami federal court.

Moïse’s murder did not start off as an assassination, U.S. investigators say, but it obviously became one.

Why did the plan change? Who were the intellectual authors behind the brazen killing? And why was Moïse murdered? Those are among the enduring mysteries in this international whodunit. The investigation in Haiti is on its fifth judge, and nearly a year and a half later none of those detained has been officially charged.

In the United States, the case is moving, albeit slowly. Rodolphe Jaar the drug trafficker, former Sen. John Joël Joseph and a Colombian, Mario Antonio Palacios Palacios, all agreed to be transferred to the States after escaping to the Dominican Republic or Jamaica. Palacios told U.S. investigators that some co-conspirators were informed on July 6 — the day before the assassination — that the plan was to kill Moïse.

This past July, a federal judge in Miami granted the request of prosecutors to seal evidence about the work of former — and possibly still active — U.S. government informants connected to the plot. The protection of classified evidence could affect what the public ultimately learns about the assassination.

There is nothing to guarantee that a presidential assassination in Haiti cannot happen again. As head of state, Moïse had no shortage of political enemies. His chest-thumping, cascade of worrying legislation during one-man rule, attacks on the private sector, infighting and the growing distrust within the PHTK political party over his successor and own personal involvement with corrupt individuals created a perfect storm.

Just as there is no shortage of suspects, there is no dearth of motives. At the time of his death, Moïse was nearing the end of his presidential term, according to his calculation, and he faced the same uncertain future as every Haitian president before him: Would he be allowed to finish peacefully? Would he be killed, imprisoned or exiled like more than 30 others who preceded him?

Amid pressure from a June 8-10, 2021, Organization of American States mission on the deteriorating political climate in Haiti, Moïse and his supporters knew the political ship was sinking. His choice of Henry, 73, as prime minister was not welcomed by all. In tapping the former interior minister, Moïse needed to issue a presidential order overriding a law that set a prerequisite for running. That law required anyone who previously managed public funds to get an audit certificate known as a “décharge” from Parliament clearing them of past mismanagement or corruption.

Moïse’s executive order opened the door not just for Henry but for other political figures whose candidacies for public office had been stymied. Others were already lined up waiting for Moïse to pass the political torch.

“He said this decision has death in it,” a former senator who spoke to the president recalled.

Hours after uttering those words, Moïse was murdered.

Acknowledgments

Contributors: Miami Herald Haiti/Caribbean Correspondent Jacqueline Charles / El Nuevo Herald/Miami Herald Reporter Antonio Maria Delgado / Investigations Editor Casey Frank / Federal Courts Reporter Jay Weaver / McClatchy Senior White House and National Security Correspondent Michael Wilner / Miami Herald Investigative Reporter Sarah Blaskey / Art directed and animated by Sohail Al-Jamea / Illustrated and storyboarded by Rachel Handley / Design and development by David Newcomb / Copy edited by Mary Behne.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies