‘It’s been a long time.’ Alberto Ibargüen retiring from leadership role at Knight Foundation

Alberto Ibargüen, president and CEO of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Miami-based philanthropy that has profoundly influenced media coverage and arts and culture programs across the country, is retiring, the foundation announced on Friday.

Ibargüen, 79 and famously energetic, avoided the R word himself, preferring to say he is “stepping down” but stressing that he doesn’t intend to step away from issues he has championed. The reasons for the move are numerous, both professional and deeply personal.

“It’s partially a question of time in the office. It’s been a long time. It’s been 18 years. It’s been, gosh, it’s been just a fantastic, fantastic run. A fantastic opportunity,” said Ibargüen, who was publisher of the Miami Herald and el Nuevo Herald before agreeing to oversee the multibillion-dollar endowment of the Knight Foundation.

“Enormous changes” in his personal life — really one heartbreaking one — also played a big role in his decision.

In August 2021, his wife, Susana Ibargüen, a civic leader and a board president at Pérez Art Museum Miami, died at 76 after a two-year battle with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a neurological disorder known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. They’d been married 53 years and together nearly six decades. He is, he acknowledges, still processing the loss.

“That’s not something that you just say ‘OK’ and ‘that was then and this is now.’ Well, no. That’s something that I’m still dealing with and still sort of exploring and trying to think, ‘What is my life with her in spirit but not in person?’ and how that changes,” Ibargüen said in a reflective two-hour interview with the Miami Herald.

“We changed over time. We had seasons where we were really close and seasons when we were further apart and we were always committed to each other,” he continued. “Relationships are complex and they’re not linear. Being married to somebody that was that interesting and that challenging, I think, was freeing in a way. We had a home. I don’t know if I have the vocabulary for this. But home was safe. ... Everything else was easy, was easy to explore.”

Her mark on his life, he said, is indelible. “What remains, of course, is wonderful. It’s a spirit. It’s an attitude. It’s a strength. It’s an appreciation for things. But it isn’t the same.”

The Knight mission

Ibargüen, at age 60, left the Miami Herald in July 2005 to oversee the multibillion-dollar fund of the Knight Foundation. It had been created in 1950 by John S. and James L. Knight, brothers who led one of America’s largest and most successful 20th-century newspaper chains, which included the Miami Herald. According to the foundation, which moved its headquarters to Miami in 1990, the Knight family “believed that a well-informed community could best determine its own true interests and they entrusted future generations of trustees to do just that.”

Ibargüen took that mission to heart. Under his leadership, the foundation has poured $2.3 billion into media, tech development and arts and community-building organizations locally and in states where the Knights had papers, the foundation reported.

In addition to Miami, the Knight Foundation operates in seven other cities: Akron, Ohio; Charlotte, North Carolina; Detroit; Macon, Georgia; Philadelphia; San Jose, California; and St. Paul, Minnesota. The foundation also partners with local community foundations in 18 communities nationally.

Ibargüen, who once was a Peace Corps volunteer in Venezuela, says he admired the Knights’ style. He’s tried to honor their mission but in his own fashion and with a clear view of changing times. Ibargüen has particularly focused on investing in digital media and arts and culture.

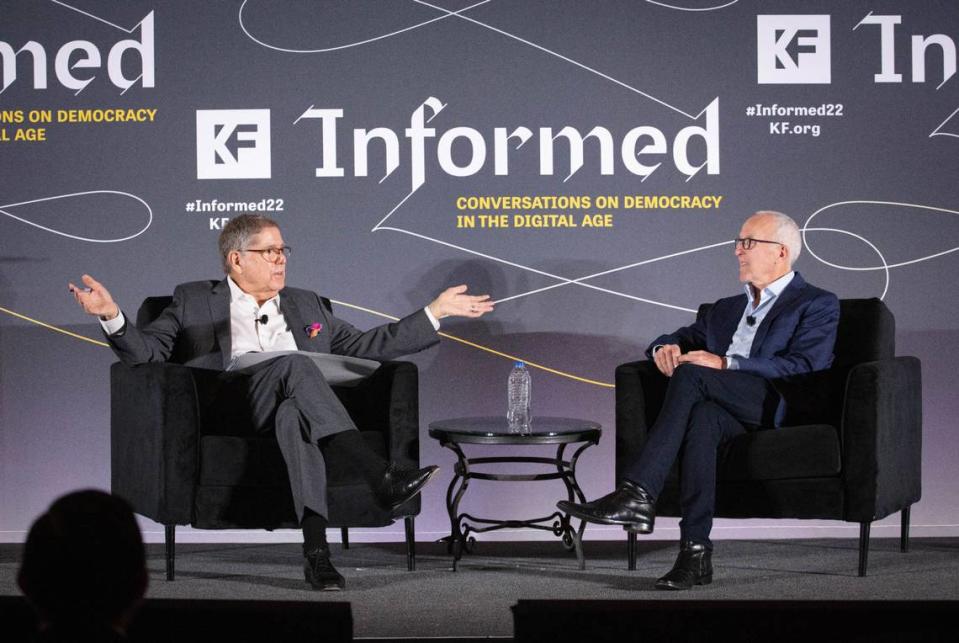

“He has been visionary in his approach,” said Francisco Borges, chair of the Knight board. “Digital transformation has pushed us to find new ways to sustain our democracy and Alberto has provided us with the tools to do just that.”

During his 18-year Knight Foundation tenure, the foundation’s investment in the arts in Miami has surpassed $200 million.

Ibargüen pursued a strategy in keeping with the Knight brothers’ mission.

“My view from the beginning was that this was less a charity and more a social investment opportunity,” he said. “In a charity, traditionally, you make the grant and you walk away. You’ll be rewarded in heaven. That didn’t strike me as a way that the Knight brothers ran their business. They were thinking about this as a social investment. You look in the community, you see what the issues are. You decide which ones you can do something about, and which ones you might have some impact on — short or long-term. And then you focus on those.”

Journalism and digital media

Ibargüen’s first focus after joining the Knight Foundation was journalism, since he felt he could tap 25 years of experience. He had led newspapers that included Newsday in New York, the Hartford Courant in Connecticut, the Miami Herald, and el Nuevo Herald, which he upgraded from an insert in the Miami Herald to a stand-alone Spanish-language publication.

“Jack [Knight] — and I — wrote that the purpose of a great newspaper was to inform and illuminate the minds of readers so that the people may determine their true interests. .... When they’re engaged they can get to a better functioning democracy. So that’s the general approach,” Ibargüen said.

But by 1996, the year the Herald launched its website edition with breaking news coverage of the ValuJet Flight 592 crash into the Everglades, he began to see that the audience sought engagement elsewhere. He sensed the digital revolution about to forever change the media landscape.

“I had seen this incredible change from the amazing dominance and influence of newspapers. ... It even set the agenda for what was going to be on the TV news that night. And then all of a sudden it wasn’t. The technology was allowing the crowd to go someplace else,” Ibargüen said.

The newspaper industry’s first steps into the online world were really stumbles, he said.

“We thought at first we just put the newspaper on the web and people would trust the brand. Because we were a trusted brand. And that didn’t work. We weren’t putting the web information through the same rigorous editing process that we would have for the newspaper,” Ibargüen said.

His recognition of the industry’s struggles would spark what would become the Knight News Challenge, which sought to find and then support bold experiments using news and information delivered to geographically defined communities on digital platforms.

Ibargüen’s pitch to the Knight board was sober. He told them they had to admit that they were the biggest trainers of journalists in the world — with 20 endowed chairs in journalism at schools around the country — and that while they could see what was coming, they didn’t have a clue about what to do about it.

“But we do have one thing that nobody else has, which is this amount of cash called the endowment,” Ibargüen said. “And so let’s offer that and see what happens. And then with that first Knight News Challenge, with just those three relatively clear but undefined rules of geography, digital, and local news and information we had thousands of ideas within two or three years.”

Even the technological geniuses at MIT became recipients of major grants. And the investments there continue. Knight’s investment in technology in Miami alone in the last 10 years, since 2012, tops $60 million, according to foundation figures.

In 2019, after decades of striving to explore different approaches to helping local news organizations adapt to a drastically altered media environment, the foundation invested $300 million over the next five years to re-imagine local news, build new business models, bolster investigative reporting and connect with audiences through technology and civic engagement.

“Knight took a position that was there for the taking as the intermediary between journalism and technology, and I think we did OK,” Ibargüen said.

Arts and culture

The arts in South Florida became Ibargüen’s other driving mission for the Knight Foundation. The push to promote arts and culture in Miami topped $200-plus million since he led the foundation.

“It’s hard to imagine anybody in the history of this community that has had more of an impact on the cultural firmament than Alberto,” said philanthropist, filmmaker and art collector Dennis Scholl.

Scholl served as the Knight Foundation’s vice president of arts for seven years during Ibargüen’s tenure. Scholl oversaw the distribution of nearly $100 million to organizations and nonprofits such as the New World Symphony; the University of Miami’s Frost School of Music; the O, Miami poetry festival; and the Borscht Film Festival.

Scholl left Knight to head Art Center/South Florida on Miami Beach’s Lincoln Road Mall in 2017. Art Center, founded by the late Ellie Schneiderman, became Oolite Arts, a studio and exhibition space for visual artists. Scholl is its CEO.

READ MORE: How this lifelong art collector made the switch to filmmaker

“He was an incredible person to work for. He lives and breathes and believes in the culture, the art of this community, and so many other communities across America. But in particular, in Miami, where his heart is,” Scholl said of Ibargüen. “Such a debt of gratitude for providing the fuel that has allowed our cultural community to blast off.“

Ibargüen was Puerto Rican-born, New York-reared, and educated at Wesleyan University and the University of Pennsylvania Law School. He realized that like him, three-quarters of the area’s population had roots that were originally elsewhere. He saw the arts as a way to stitch together the region’s multicultural community.

“That means that we need to find ways to come together to figure out the new Miami, to come to figure out who we are,” Ibargüen said. “What is the Miami of our dreams? ... We ultimately decided on arts and culture as the place where everybody in Miami had some kind of participation.”

There already were strong arts bones, some decades old. The Latin music labels, including Gloria and Emilio Estefan’s recording studio on Bird Road, have offices here in Miami. World-renowned music from Aretha Franklin to James Brown, Fleetwood Mac’s “Rumours” to the Eagles’ “Hotel California,” and the Bee Gees’ feverish ’70s run of hits, have been recorded at North Miami’s Criteria Studios since its opening in 1958.

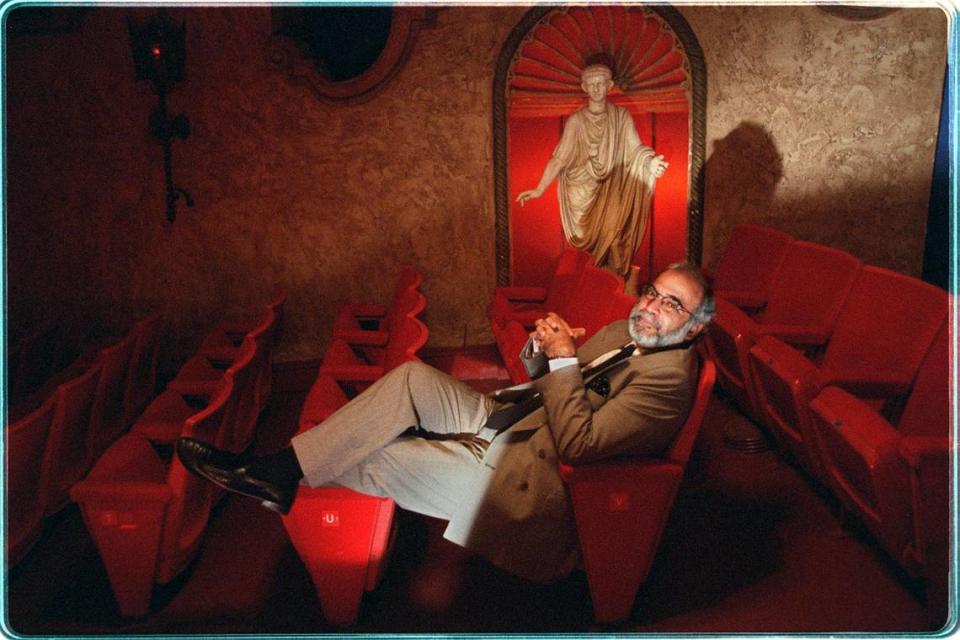

In addition, “The Miami International Film Festival was going great guns and Miami Dade College stepped in and saved a terrific institution in this town thanks to Nat Chediak and Eduardo Padrón,” Ibargüen said. “We had one of the biggest book fairs. Thank you, Mitch Kaplan. This amazing book fair in a place that had, you know, not exactly the greatest reputation as a bunch of bookworms.

“And we had a stunning, very high-quality collector community, which is one of the things that initially attracted [Fondation Beyeler director] Sam Keller from Art Basel in Switzerland. The collector community absolutely turned itself inside out to break Art Basel here, led by Norman Braman, but including [Carlos and Rosa] de la Cruz, including the Margulies, including Rubell. These folks were amazing in the way they opened doors to their homes and to their collections to bring you Basel here.”

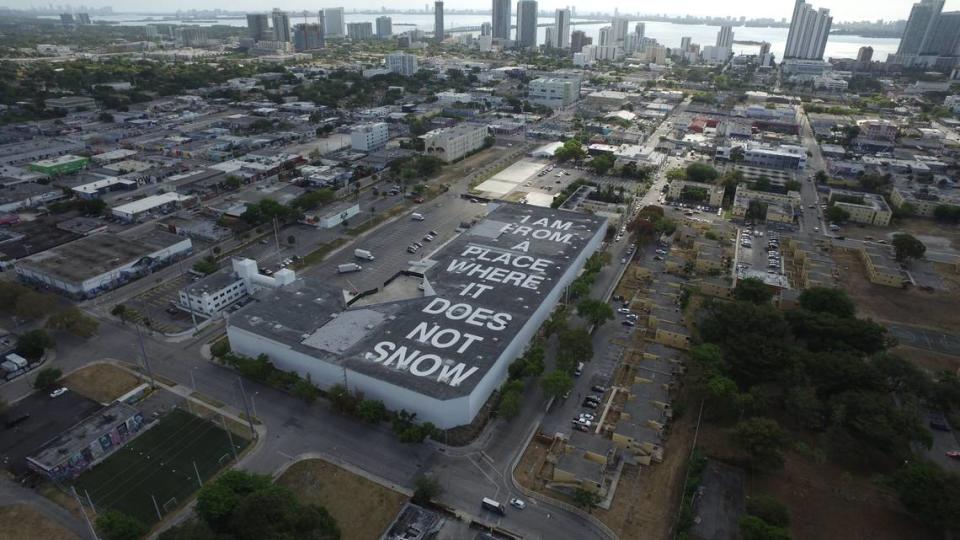

Ibargüen, through the foundation, helped fund the Pérez Art Museum Miami, ICA-Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, Sweat Records, Coral Morphologic, and The LAB Wynwood.

“Without Alberto Ibargüen, there is no Give Miami Day. Full stop,” Javier Soto, former CEO of The Miami Foundation, told the Miami Herald in November 2021, on the 10th anniversary of the day devoted to philanthropy in the Magic City.

READ MORE: Ten years in, Give Miami Day goes from barely known to spreading millions to nonprofits

Leveraging attractions

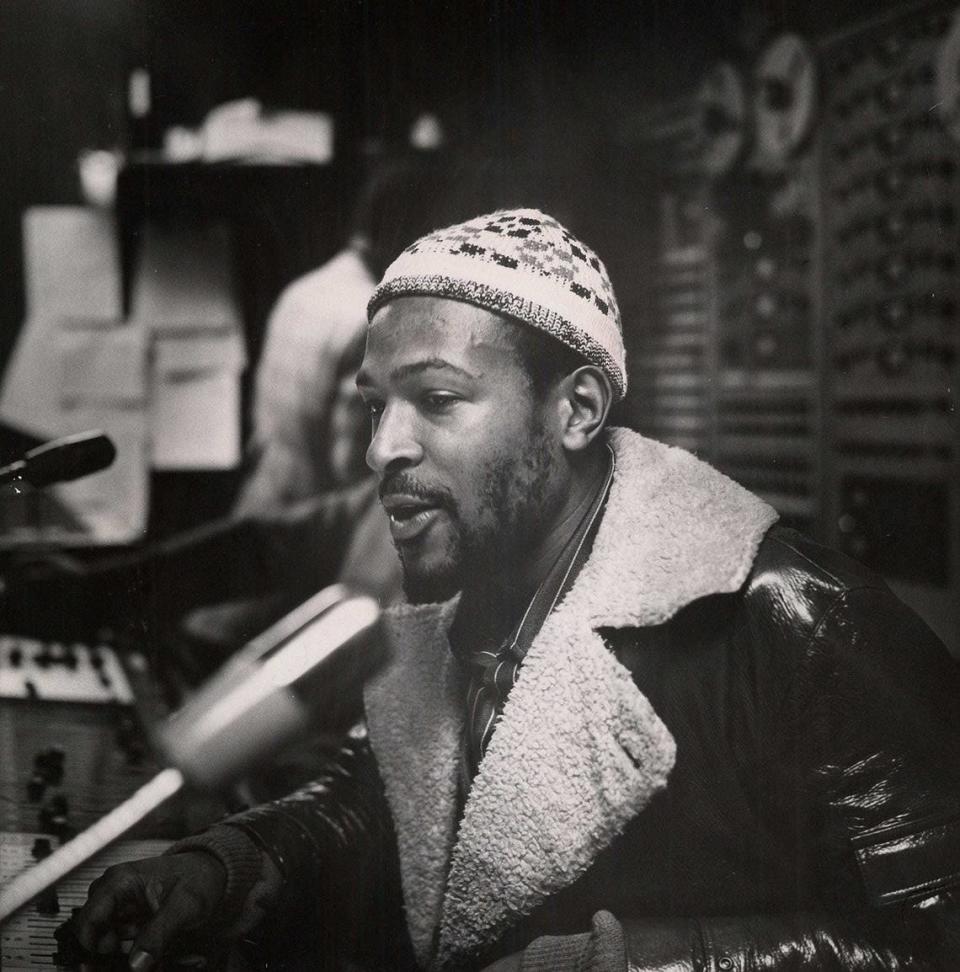

He’s also the impetus for the $4.5 million funding of the digitization of Motown archives for the Motown Museum in Detroit as part of a $23 million investment in the digital future of the arts in Detroit. The idea struck Ibargüen when he heard unreleased work tapes of Marvin Gaye and musicians cutting the landmark 1971 recording “What’s Going On” in Los Angeles and Detroit studios. “I talked to the woman who runs the Motown Museum and I said, you know, everybody should be able to hear this.”

‘A visionary leader’

Says Borges, the Knight board chair: “Alberto has been a steadfast and visionary leader of the Knight Foundation and worked tirelessly to impart the vision of John and James Knight in an era that they only could imagine. His passionate pursuit of innovative and bold ideas that support the Foundation’s mission regardless of the pressures and challenges to our democracy and society is his legacy.”

His former boss at the Herald echoed those thoughts.

“One of the best things I ever did was hire Alberto Ibargüen in 1995 as the publisher of el Nuevo Herald,” said David Lawrence Jr., back then the publisher of the Miami Herald and now chair of the Children’s Movement of Florida. “He succeeded me as publisher when I retired in 1999 and was a simply superb leader for the Herald and subsequently for the Knight Foundation. Smart. Wise. Tough-minded in the best way. And a heckuva contributor with a vision for an ever-better Miami.”

For now, Ibargüen has not solidified long-term plans. “I honestly don’t know what’s next and I don’t know if something’s next. I suspect something will be.”

He know he intends to stay in Miami, the adopted town he’s had a profound cultural influence on for nearly 30 years. He says he will split his time between here and New York, where his son Diego, 47, daughter-in-law, and three grandchildren live. He also will stick around as the Knight Foundation’s board of trustees conducts a national search for a successor, which begins immediately — one that will continue to carry out the Knight brothers’ mission.

“I intend to run through that finish line, as if I were starting the race,” Ibargüen said. “And anybody who thinks otherwise is not paying attention to the things that we’re still funding and are continuing to develop.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies