‘We’ll still be watching in 50 years’: how Raymond Briggs’s The Snowman changed Christmas

Some people are so famous for so long that they become enmeshed in all our lives. Raymond Briggs, who died on Tuesday, was one of those people. Briggs illustrated his first book, Ruth Manning-Sanders’s Peter and the Piskies: Cornish Folk and Fairy Tales, 64 years ago, and quickly set about creating a string of classic books, many shot through with his trademark melancholy. Fungus the Bogeyman revelled in a quiet British mundanity; When the Wind Blows was terrifying enough to scar an entire generation emotionally, and Ethel & Ernest managed to convey the small hopes and thwarted ambitions of mid-20th century life in a way that would put to shame many important authors covering the same period.

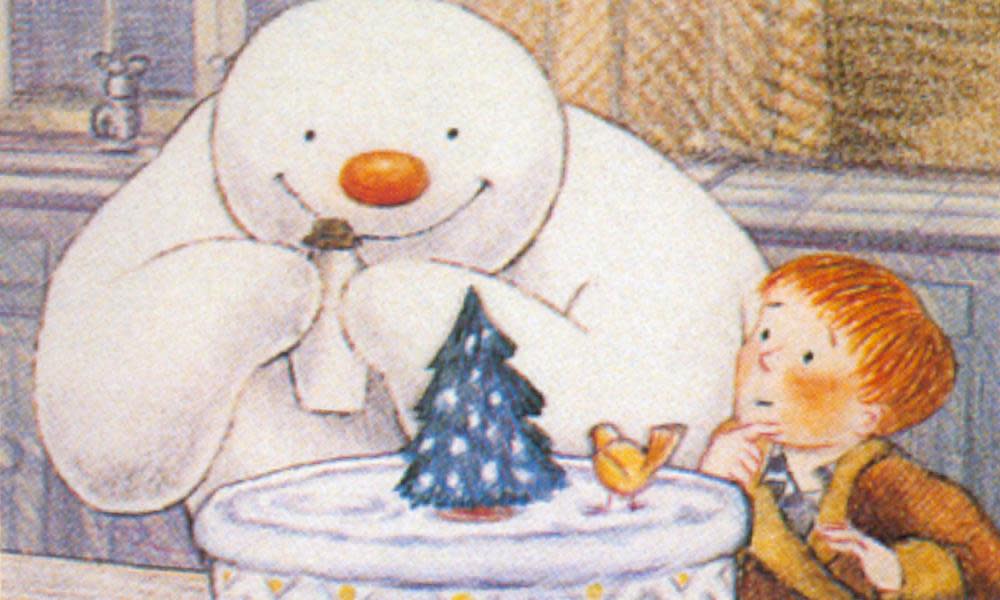

And yet, despite this breathtaking output, The Snowman looks set to be Briggs’s defining work. First published in 1978, The Snowman was a wordless picture book that Briggs saw as a counterpoint to the murk of Fungus, something he designed as “clean, pleasant, fresh and wordless and quick”.

However, when you think of The Snowman, you probably don’t think of the book. This is because the animated TV adaptation instantly became an indelible part of British culture. The Snowman was first shown by Channel 4 on Boxing Day 1982, and was such a success that it was nominated for an Oscar. It is a testament to the power of the film that this fact – one that most animated shorts would brag about loudly – has largely been forgotten. Instead, we collectively clutched The Snowman to our hearts with such intensity that it is almost impossible to imagine life without it.

It’s a work of incredible beauty, hand-drawn and animated in such a way that it feels as if it could slip through your fingers at any moment. Lines blur and shapes shift. The textures of the characters’ clothes dance relentlessly. During a motorbike sequence, trees fly at the camera so quickly they become abstract. At times, it can feel hallucinogenic.

And then there is the song. Howard Blake’s Walking in the Air is a pure and weightless daydream. It’s the only point in the film where we hear a human voice, and it accompanies a spectacular sequence where a snowman and a boy fly to the north pole.

I’m old enough to remember The Snowman from the start, in the early 1980s when my mum invariably made a big deal about the family watching it together. Over the years, it became a Christmas tradition, holding steady through the weird phases when it was introduced by David Bowie and Mel Smith. And with repeated viewing comes familiarity and then, sadly, boredom. Something I’ve noticed about people my age is that The Snowman became such a part of our culture that it was easy to mock. The sincerity of Walking in the Air, especially, made it an easy target for ridicule.

Everyone comes back to it in the end, however. This is down to The Snowman’s secret weapon: the precision with which it nails the low-humming sadness of Christmas. The snowman and boy have the adventure of a lifetime but, the next morning, the snowman has melted. In the final shot, the boy stands over a mound of slush, attempting to process his grief. There’s no reassurance, no promise of a return. Everything you love will one day leave you. Merry Christmas.

This element of The Snowman gives it the unerring ability to change with you as you age. Watching it with my children now, with my mum no longer with us, The Snowman somehow means even more to me than when I was a child. This why we’ll still be watching it 50 years from now.

The Snowman changed Christmas television, too. Every year we are inundated with animated picture-book adaptations where the melancholy is ramped up. Sometimes they work (Julia Donaldson’s Stick Man, about a stick who aches with loneliness), and sometimes less so (Michael Rosen’s We’re Going on a Bear Hunt, which was overlaid with a truckload of imported faux-sincerity), but they can all be traced directly back to The Snowman.

We might be in the grip of a scorching hot August, but don’t be surprised if Channel 4 screens The Snowman in the next few days to commemorate all of Raymond Briggs’s remarkable achievements. And don’t be surprised if a ton of people watch it.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies