Liz Truss: are the Conservatives facing an electoral meltdown?

The Conservative party is heading into its annual conference amid the catastrophic fallout from Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-budget. The decision to cut tax without a plan to pay for it caused a sharp fall in the value of the pound on currency markets, which reached an all-time low against the dollar in Asian markets, and a rapid rise in costs of government borrowing. Both are indicators of the strongly negative reaction of financial markets to the mini-budget.

Party members, who were, after all, the ones who chose Truss as prime minister, will now be wondering whether their choice (and the abrupt change of direction in economic policy it enabled) will cost them the next election. And they are right to be worried.

According to the most recent YouGov survey Labour is a staggering 33% ahead of the Conservatives in voting intentions, gathering 54% of the vote in total. If sustained, that would give the party a majority in the House of Commons larger than Tony Blair’s victory in 1997.

It is worth remembering the last time the Conservatives lost the confidence of the voters in their ability to manage the economy. This was on “Black Wednesday” in September 1992, when the British government lost control of the pound. A collapse in its value forced Britain out of Europe’s shared monetary system, causing market chaos. They did not regain that confidence until David Cameron became the leader in 2005.

Only 19% of respondents in a poll conducted just after the recent announcements took place thought the mini-budget would make them better off and 29% thought it would make them worse off. That said, 53% thought that the measures would make no difference to them or that they did not know the effects, indicating that at that stage the jury was out for many voters.

Haunted by history

Comparisons have been made with Conservative chancellor Anthony Barber’s budget of 1973, when Edward Heath’s government massively increased public spending with the aim of stimulating economic growth at a time when inflation was rising. This ended badly for his government because Labour won the 1974 election.

However, a more apt comparison is with Margaret Thatcher’s first term of office from 1979 to 1983. It was during this period that her government embarked on a radical change in economic policy by embracing “monetarism”.

The aim was to reduce the rapidly rising inflation by applying the ideas of Milton Friedman, the University of Chicago economist who argued that the only way to curb price rises was to restrict the supply of money. In practice this involved raising interest rates to very high levels, thereby making borrowing much more expensive and slowing the economy down, with rising unemployment as a result.

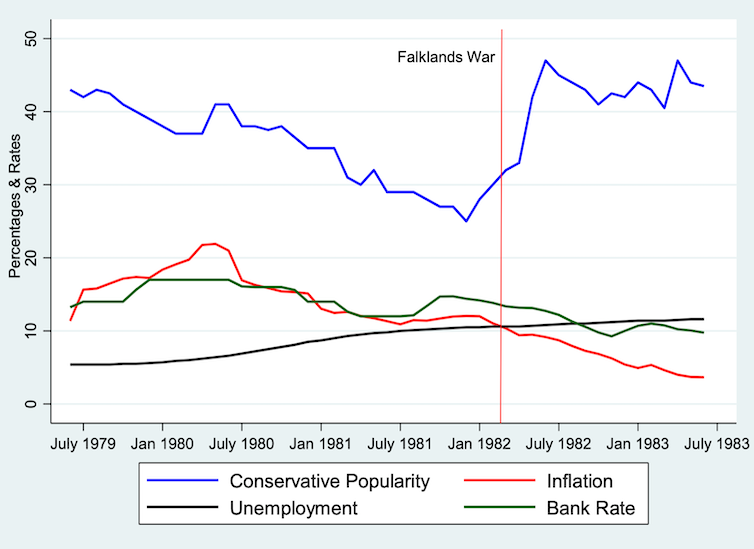

The chart below shows inflation, unemployment, interest rates (known as bank rate) and Conservative vote intentions in the polls from July 1979 to June 1983. The government raised interest rates from 12% just before the election to 17% by December that year, far higher than anything we see at the moment.

Voting Intentions, Unemployment, Inflation & Bank Rate, 1979 to 1983

As a result, inflation peaked at 22% in May 1980 and subsequently started to decline at the cost of rising unemployment, which reached 9% by the start of 1981 and subsequently kept on rising. This is a relationship – that is, the trade-off between unemployment and inflation – is known as the “Phillips Curve”.

For a period, this produced stagflation or a combination of high inflation and high unemployment. By March 1982 they were both running at over 10%.

This produced a rapid decline in support for the Conservative government and by December 1981 voting support for the party had fallen to 25%. However, the situation was radically changed by the Falklands war which started in April 1982. As a result support for the government soared, particularly after the victory in June of that year.

What are the lessons from this for the present government? Inflation is currently running at an annual rate of 9.9 %. In this situation the Bank of England is following its mandate and has raised interest rates to 2.25% – their highest level since 2008.

The Bank thinks that Britain is already in recession so while unemployment is low at the moment it is likely to rise next year. In addition, monetary policy is now in conflict with fiscal policy, with the Bank raising rates to fight inflation while the Treasury’s current spending plans are likely to make it worse.

Read more: Only a U-turn by the government or the Bank of England will calm UK financial markets

This means that we could see a return to stagflation, particularly if the response by financial markets to the mini-budget continues to be very negative because they are spooked by unfunded spending and tax cuts.

If the pound’s value stays low it will have the effect of creating additional inflation because imports will all cost more. In addition, rising costs of government borrowing have the potential to create a spiral of increasing debt and higher interest payments.

If we are entering another period of stagflation comparable to that of the 1970s this will be toxic for government voting support at a time when it is very unpopular. It looks like Truss would need another Falklands war to save her government.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies