In a post-Roe America, abortion medication looms as the next legal battleground

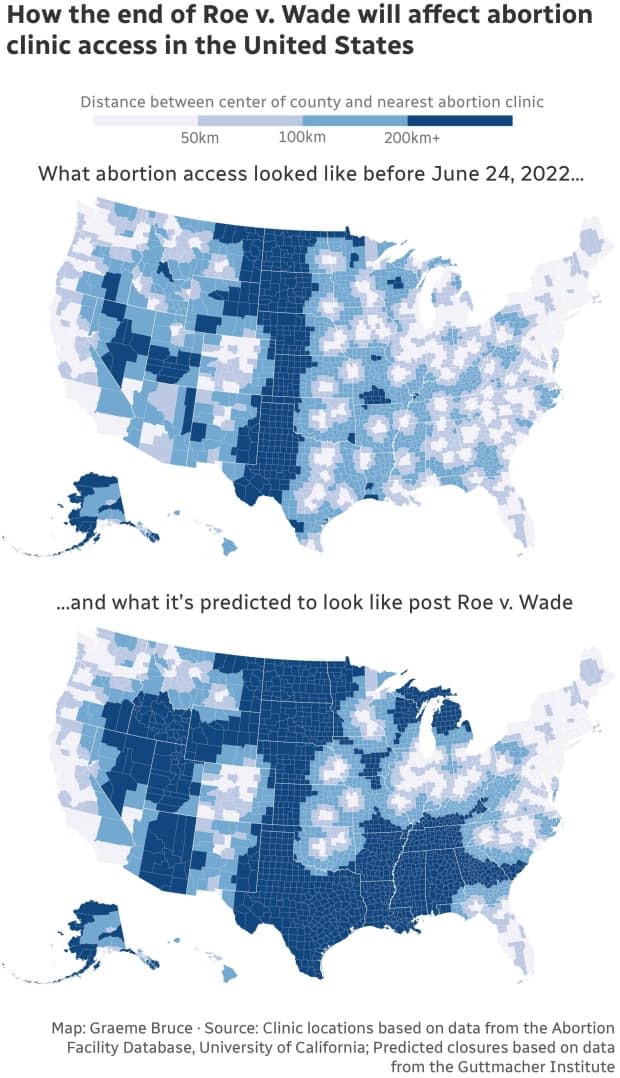

The overturning of Roe v. Wade has sparked legal battles across the U.S., as individual state trigger laws that restrict access to abortion procedures. But the legal status of medication used to terminate pregnancy could see the fight enter an even-murkier legal zone.

Since the U.S. Supreme Court ruling last month, states that have restricted abortion have made it clear this also applies to abortion through medication — a method now used in more than half of all abortions in the country.

But that has raised questions about enforcement of such laws, and whether states actually have the power to ban drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

It also means that it's very likely the country's top court isn't finished with the issue of abortion.

"It would almost certainly end up back at the Supreme Court, and there's no telling how the conservative justices will rule," said Lawrence Gostin, the faculty director of the O'Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

Percentage of abortions that are medication abortions

2 drugs used for medical abortion

A two-pill regimen is used for medical abortion — mifepristone and misoprostol — which is approved for use in the first 10 weeks of pregnancy.

Mifepristone, taken orally, prevents an existing pregnancy from progressing by dilating the cervix and blocking the effects of the hormone progesterone, while misoprostol, taken 24 to 48 hours later, works to empty the uterus by causing cramping and bleeding, similar to an early miscarriage.

The use of the medication can be self-managed at home and no medical procedure is necessary afterward. But the drugs are subject to restrictions at both the state and federal levels.

WATCH | Renewed focus on abortion pills in wake of U.S. Supreme Court decision:

For years, the FDA required that individuals seeking mifepristone go to a medical clinic to acquire it. But in December 2021, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal agency lifted that requirement, meaning the drug could be obtained by mail — although it would still need to be prescribed by a certified health-care provider.

With some states now banning abortion medication, pregnant people in those jurisdictions will have to either travel to another state where abortion remains legal or have the pills mailed to them from those states or abroad through organizations such as Aid Access, a European non-profit organization that mails pills to women in the U.S.

This new battleground had started to form before the Roe ruling, as some states had made the legally nebulous decision to ban the practise of telemedicine abortion and prohibit residents from receiving abortion medication by mail.

Still, the enforcement of such laws may face challenges.

Enforcement challenges

Targeting people's mail, for example, would be difficult for state authorities, who have no jurisdiction with the U.S. Postal Service, an independent federal agency, explained Rachel Rebouché, an expert on reproductive health law and the interim dean of Temple University Beasley School of Law in Philadelphia.

"States don't have the authority just to ransack the mail without a warrant," she said. "I think it's hard [to enforce]. States could get warrants; they could potentially police the mail. But that's difficult — and they probably know that."

It's possible states could treat abortion medication like illegal drugs, going after individuals for possession. But many anti-abortion groups have said they don't support criminalizing abortion patients.

Medication-banning states could also seek to prosecute across borders.

A draft paper co-authoured by Rebouché — titled "The New Abortion Battleground" and set to publish in the Columbia Law Review — raises the issue, suggesting that "out-of-state, as well as out-of-country, providers could be guilty of state crimes by offering these telehealth services."

"In a post-Roe world, anti-abortion states will struggle to establish jurisdiction over these out-of-state providers, while abortion-protective states will attempt to protect their providers from out-of state prosecutions," the authors write.

On the other side, some states where abortion remains legal have introduced laws to protect abortion providers from extradition to states where the practice is banned.

But Gostin said it would be extremely difficult for one state to charge or penalize a health-care provider who prescribes abortion medication in another state. "States have no jurisdiction outside of their state boundaries."

Federal court case over ban on pills

As the country's abortion laws continue to shift, individual states could eventually find themselves in legal battles over the FDA's approval of abortion medication.

Shortly after the Supreme Court ruling, Attorney General Merrick Garland released a statement, hinting at how some abortion restrictions might be fought.

"We stand ready to work with other arms of the federal government that seek to use their lawful authorities to protect and preserve access to reproductive care," he said. "In particular, the FDA has approved the use of the medication mifepristone. States may not ban mifepristone based on disagreement with the FDA's expert judgment about its safety and efficacy."

Many legal eyes are also locked on a case before a federal judge in Jackson, Miss., that involves the maker of a generic version of the drug.

GenBioPro Inc. is arguing that the FDA's approval of mifepristone should override any state ban and the overturning of Roe v. Wade does not allow Mississippi to stop it from selling the pills in the state.

That argument is the theory of "pre-emption," said Amanda Allen, senior counsel and director of the Lawyering Project, an organization that represents abortion providers.

"[It's] the idea that if the federal government has kind of staked its claim in an area of law, that federal law will trump state law," Allen said.

In the Mississippi case, she said, that would mean the FDA, by regulating, approving and putting restrictions on mifepristone, has essentially "occupied the field and that state law to the contrary should be invalidated."

Gostin agreed that the FDA may assert supremacy and that its scientific approval of abortion pills should pre-empt any state law that bans or restricts that access.

"The U.S. Department of Justice could challenge any state restriction on abortion medication, based on the claim that FDA sets a national uniform standard based on science," he said. "States can't pick and choose which FDA-approved drugs it will and won't allow."

States could argue, however, that things have changed since the overturning of Roe v. Wade.

Mississippi, for example, said in an opposing filing that "the legal landscape … has shifted overwhelmingly in favour of the state's authority to regulate or prohibit abortion," and that there was no evidence that Congress ever intended the FDA to restrict states' ability to regulate abortion.

"There's lots of arguments that states can make," Rebouché said. "They can say they're not trying to regulate safety; they're trying to regulate morality or protect potential life.

"They could say that this was not the congressional purpose in giving the FDA this power."

Katie Watson, a constitutional scholar and medical ethicist at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University, recently told the New York Times that the ability of the federal government to assert that the FDA's approval takes precedence over state laws is limited, "given, traditionally, states get to regulate the practice of medicine."

Issue not yet legally tested

Rebouché described the whole legal issue as a kind of a "novel incident," she said, "where half the country is going to try to ban an FDA-approved drug."

While the issue is being debated, she said it hasn't really been legally tested yet. "So it would have pretty huge consequences."

If a federal court said states cannot regulate or ban medication abortion, based on the pre-emption theory, that would certainly have national implications, said Allen.

"The real question is whether the Supreme Court, as currently constituted, would uphold that kind of a ruling."

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies