How leading thriller writer helped reveal plagiarism of Emmy prizewinner

It was a just few seconds of vivid footage: joyous scenes of American troops on tanks and Jeeps driving down a Champs Élysées lined with cheering Parisian crowds. But the rare colour sequence, shot by one of the Hollywood greats, film director George Stevens, sparked a chain of events that has ended in scandal and embarrassment for Stevens’s son and for leading US TV awards the Emmys.

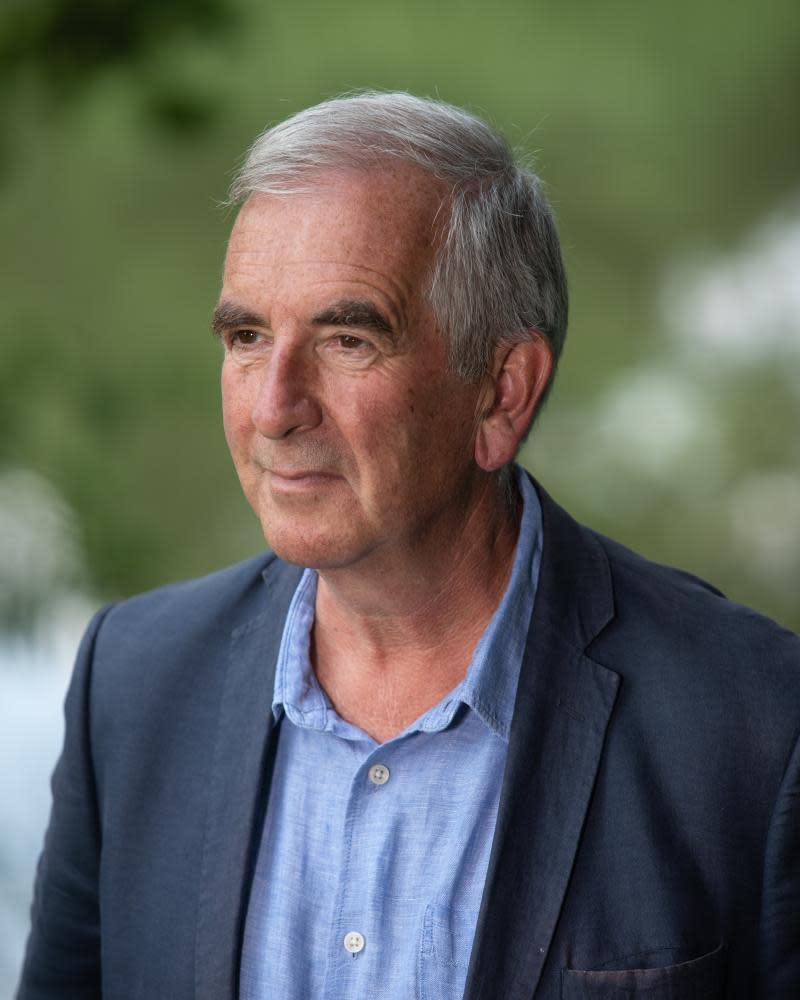

Now for the first time, the former BBC producer Paul Woolwich and his collaborator, the renowned novelist Robert Harris, have revealed the full story behind an unprecedented decision to quietly strip a trio of top awards from two leading American film-makers after the realisation that their work on a 1994 documentary had come from a BBC Newsnight film already broadcast in Britain in 1985.

“I feel it is rather sad,” said Harris this weekend. “We worked on the original film in good faith and I had no idea our work had been used again in this way until Paul told me.”

Woolwich, an acclaimed current affairs producer who left the BBC in 2008, said this weekend that a wrong that had endured for a quarter of a century has finally been put right. “I felt a grave injustice had been visited upon those who had created the original documentary and whose work had been claimed by others. And I wasn’t going to let this stand, despite the passage of time,” he said.

In 1994, in front of a TV audience of 21 million, George Stevens Jr and his film editor, Catherine Shields, were handed three coveted statuettes for their film George Stevens: D-Day to Berlin at the 46th Primetime Emmy awards, held in California.

But, unbeknown to the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences, the organisation behind the Emmys, Stevens Jr had submitted a shorter version of the Newsnight film, made with his father’s wartime footage almost a decade earlier, and had entered it as all his and Shields’s work, without proper acknowledgment.

“The level of plagiarism was astonishing, so I approached the academy’s president, Maury McIntyre, in the autumn of 2019 and asked for an investigation,” said Woolwich.

Perhaps hardest for Woolwich to believe even now, he adds, is the fact that Stevens Jr – a “big fish” in his own right, and already a multiple Emmy winner, as well as an honorary Oscar recipient in 2012 and winner of eight Writers Guild awards – was given one of his Emmys for “scriptwriting” on the documentary. In fact he had used large sections of a commentary written for the BBC by Harris, now a celebrated author.

The story began in 1985 when an influential British TV journalist in Washington watched a full-length Hollywood biopic, George Stevens: A Filmmaker’s Journey, at the end of a dinner party. That journalist was Margaret Jay, now Baroness Jay, daughter of former prime minister James Callaghan and then the wife of the former British ambassador to the US, Peter Jay.

Stevens Jr had made the film as a tribute to his father, the director of the same name who is most famous for making the western Shane, as well as the early Cary Grant adventure film Gunga Din, the Texas epic Giant, starring James Dean, and A Place in the Sun, with Elizabeth Taylor.

Halfway through the tribute film came an astounding silent documentary sequence, shot in colour towards the end of the second world war and recording the liberation of Paris. Margaret Jay was amazed, Woolwich recalled: “Colour had torn away the monochromatic veil, and everything seemed more contemporary, immediate and natural. This was the war seen precisely as those who were there saw it.”.

Stevens Sr had been sent out by the US army to film the end of the war in the Signal Corps’ special motion pictures coverage unit (Specou), together with a team of film-makers. Although shooting in black and white for the cinema newsreels, he also took out a batch of revolutionary colour film stock for his own personal record.Jay learned there was further wartime footage of D-Day beaches and of the allied bombing of Normandy, but that because of the horror of the experiences, particularly at the liberation of the camp at Dachau, the director had hidden 14 film cans away in his California attic for 40 years.

With a major wartime anniversary imminent, Jay realised the significance of the films and contacted Michael Grade, then controller of BBC One. A deal was struck with Stevens Jr, who also asked that the BBC transmit his longer tribute to his father.

Harris, who at the time called Stevens Sr’s colour images “one of the most evocative home movies in history”, recalled that the Newsnight team worked hard on the rushes in the short time available. “There were some amazing scenes, including of the V2 rocket slave factory at Nordhausen, oddly enough, since that’s the subject of my last book. We also found surviving members of the film unit and then brought it all together,” he said this weekend.Woolwich remembers trawling through the Imperial War Museum’s audio archives for authentic sound effects and finding popular songs from the exact period.

“It was all designed to breathe life, emotion and drama into the soundless images and the historic milestones they portrayed. We worked 18-hour days to meet the anniversary deadline, with the picture editor, Peter Minns, sometimes sleeping on the floor beneath his editing table,” he said.

The result was D-Day to Berlin: Newsnight Special, broadcast in May 1985 on BBC One to an audience of 10 million. Woolwich discovered the existence of Stevens Jr’s 46-minute edited version when the BBC reran his Newsnight documentary to mark the 75th anniversary of D-Day in 2019. According to Woolwich, aside from an introduction and epilogue from Stevens Jr, the film was “practically identical”, using the Dad’s Army-type graphics created by Howard Moses and original music composed by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s Peter Howell.

After seeing visual evidence, McIntyre and the American television academy asked a committee to review both films. Eight months later,and after further reviews, the decision to disqualify the 1994 entry was made last year, although the board chose not to comment.

Woolwich is grateful, he said, because the academy must know “how sensitive and embarrassing it would be, given the influential industry personality involved”. Of Stevens Jr, now 89, he said: “I can only assume that, as he believed the original raw, mute rushes belonged to him, anything created from them did too.”

Despite all the awards and praise initially handed out, this is a story in which, as Harris pointed out, “in the end, nobody really wins”.

Stevens Jr was unavailable for comment this weekend.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies