A Kroger worker killed himself. Now his family is suing, testing the 'Suicide Rule'

This story concerns suicide. If you or someone you know is thinking about suicide, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org

During Kroger’s annual shareholder meeting in June, CEO Rodney McMullen highlighted the retailer’s $1.7 billion annual profit, its continued growth and announced an increase in dividend payments.

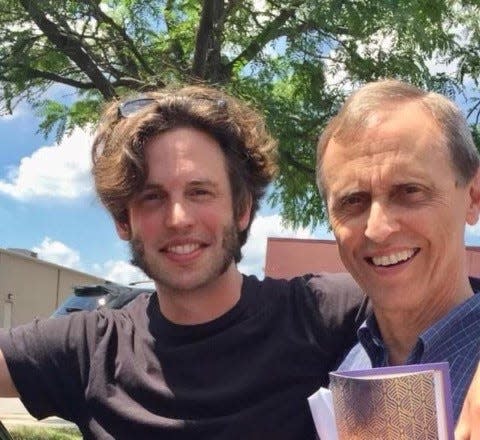

There was just one thing that threatened the upbeat mood during the virtual online forum: The father of a Kroger worker asked if the company would “take accountability for the death of his son,” Evan Seyfried.

McMullen fumbled slightly as he read a prepared statement.

“We are saddened by the loss of our associate and colleague Evan and we extend our deepest sympathies to you and your family as well as Evan’s friends and his Kroger colleagues,” McMullen said. “In respect to the sensitivity – the sensitive situation, and as a matter of active litigation, I will not comment further on the details … I’m very, very sorry for your loss.”

Seyfried, 40, was a dairy manager overseeing the section with the milk, yogurt and other products at a Kroger store in the Cincinnati suburb of Milford. His father, Ken Seyfried, is suing Kroger for wrongful death, accusing two managers at his store of harassing him during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic and eventually driving him to suicide on March 9, 2021.

In the lawsuit, Kroger managers are accused of waging a “campaign of terror” that included sabotaging his work, harassing him sexually, following Seyfried after work and sending him menacing and obscene texts.

While McMullen tried to show some compassion to the grieving father, that might be all the sympathy his family gets from the company. In court, Kroger’s attorneys are fighting the suit, and legal precedent is on their side.

The law in Ohio, as most states, observes what legal scholars call the "suicide rule” which generally restricts legal blame when someone takes their own life. Essentially, a suicide victim is faulted for their own death – it may not matter what happened (or what was done) to them beforehand.

“The Kroger defendants cannot be held responsible,” Kroger attorneys argued in court filings.

But as America grapples with a rising suicide rate that is the highest since the 1940s, public – and legal – opinion is changing and the case against Kroger and its managers may test the Ohio legal precedent that has stood for more than three decades.

Before he died, Kroger worker's texts alleged harassment

The case raises the question of whether Kroger, after years of intense competition, growth and multiple mergers, has adequate internal controls to prevent potential abuse against employees.

Kroger officials refused to discuss their response to Seyfried’s complaints or details of the case, citing the ongoing litigation. Seyfried's death has prompted multiple protests and an anti-bullying group called Justice For Evan.

The Enquirer spoke with more than half a dozen of Seyfried’s coworkers who shared dozens of text messages sent by Seyfried describing his humiliation and frustration:

“It’s kind of an embarrassing thing for a dude to say he’s being sexually harassed by a lady,” Seyfried texted a coworker about his store manager six days before his death. “She’s made the situation in the store very stressful for the last whole year.”

An Enquirer investigation reveals Seyfried wasn’t the only Kroger worker struggling under the store management. Documents obtained by The Enquirer show Clermont County job coaches expressed concern about the treatment of a 28-year-old woman with autism they were helping while she worked at the same Kroger store. They noted the store manager and supervisors treated her differently “trying to make it more difficult” for her and feared that she was being “forced out.”

The revelations come at a critical time for Kroger when it's struggling to hire enough associates to fuel its growth amid a national labor shortage. One of the largest private employers in the world with 420,000 workers, Kroger has also made a $25 billion bid to become even larger: taking over industry rival Albertsons, a deal that would give it more than 4,500 stores and upwards of 700,000 employees. How Kroger ultimately resolves this case may influence employment across the country.

The case has also emerged as more Americans struggled with despair: a record 48,344 people took their own lives in 2018 as the country faces suicide rates that have steadily climbed in the past two decades. It is the No. 4 cause of death among people aged 35-44, behind fatal accidents, cancer and heart disease. Men are four times more likely to likely to die by suicide.

Lawsuit: Boss called him ‘Antifa’ for wearing a mask

Seyfried first clashed with his store manager, Shannon Frazee, over mask policy. He wore a mask from the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. His boss allegedly retaliated by nicknaming him “Antifa” – after the anti-fascist movement and encouraged coworkers to call him that, according to a lawsuit.

From there, the pressure on Seyfried mounted as he – and family members and his girlfriend – noticed unfamiliar cars during his visits that led them to believe he was being followed. Later, he told union officials and logged in a journal obtained by The Enquirer that expired products turned up on his shelves undermining his work.

In early 2021, another store manager, Joseph Pigg, later made a point of telling Seyfried that Pigg could tap into his computer and track Seyfried's internet usage. Seyfried earned the ire of Pigg when he referred two unnamed female associates to the union regarding sexual harassment complaints they had against Pigg, according to the lawsuit. Around this time, Seyfried began getting menacing texts from unrecognized senders, one of them saying “are you going to get us?” He was also texted pornographic images, the lawsuit says. Frazee and Pigg are both named as co-defendants with their employer Kroger in the lawsuit.

Both Frazee and Pigg declined to comment for this story when contacted by The Enquirer.

On March 4, Seyfried felt so threatened he moved back home with his parents. His father insisted Seyfried see an attorney after his son finally told him all that had been happening.

Seyfried’s father, 75, who lives in the Cincinnati suburb of Loveland, still can’t believe how crazy the harassment got against his son. The elder Seyfried spent more than 30 years in human resources at Ford Motors. He wasn’t sure how much he could believe. But his son showed him some of the taunting texts. He also twice saw strange cars lingering in his neighborhood when his son visited in late February and that last week in March.

“He was in fear of his life and he was in fear of our lives. He thought we were at risk,” Ken Seyfried told The Enquirer. “He called Eric (his brother). He was sure that they were going to get Eric out in Oregon. It was that bad.”

On March 8, Seyfried and his father visited an attorney’s office, but Seyfried, who had no history of mental illness, had a breakdown and wandered out. His father found him two hours later, then took him home.

After recuperating briefly, Seyfried and his father talked until late into the evening when the son’s mood darkened again. Seyfried was afraid his managers were going to “get him” and that “things would get ugly,” according to the lawsuit.

Early the next morning, Seyfried’s dad found his son dead with self-inflicted cuts to his wrist, arms and throat.

A year and a half later, Seyfried's father said he relives the four hours after he discovered his son's lifeless body every day.

“It was like having a torch forced down my throat and burning my insides raw,” Ken Seyfried said. “I had nothing left.”

Can work make you suicidal?

Understanding why someone ends their own life is a challenge because it often happens in isolation, experts say. Friends and loved ones don’t see it coming because the victim doesn’t let them in. Afterward, mental illness is often blamed.

“It’s not just mental illness … What’s happening in the workspace, the job market might be contributing to stress but also eventually degrading people’s well-being,” said Craig Bryan, director of the Suicide Prevention Program at Ohio State University and a professor with its Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health. “We have largely underestimated the role of these social factors including workplace dynamics and how it contributes to suicide risk.”

Julie Cerel, a professor of mental health and director of Suicide Prevention & Exposure Lab at the University of Kentucky, said bullying or harassment at work or school could increase someone’s risk of suicide, but most people who experience these or other risk factors don't kill themselves. She added suicides are prompted by a combination of things in the victim’s life.

“Suicide is never due to just one thing. It is always a complex mix of a variety of factors and the meaning of those stressors to each person,” Cerel said.

Dozens of text messages Evan Seyfried sent to colleagues and his girlfriend and his journal obtained by The Enquirer offer a glimpse into his state of mind in the days before he died. Notably, they are not the rantings of a disturbed or disgruntled employee. They discuss stressful work situations but reflect someone trying to deal with their problems and take them in stride.

“Good morning baby! How are you this morning?” he texted his girlfriend, Amy Chamberlin, in a sporadic exchange on March 3. “Trying (not) to text as much on the clock, feel like all eyes are on me.”

Hours later, they bantered about leaving work, short staffing and the need for music emojis.

But something else happened that day that Seyfried shared with a coworker regarding his difficulties with his store manager.

“Basically, she (made) me feel uncomfortable in a sexual way a couple of times, and it happened again today,” he wrote. “So I told her she made me uncomfortable … then told the union. Yep, totally nuts.”

In a handwritten complaint included in the lawsuit, Seyfried said Frazee flashed her cleavage at him twice during a meeting.

A day later, Seyfried’s tone is more frazzled with his girlfriend. It was the same day, according to the lawsuit, his section was being inspected by a regional manager that went poorly.

“This is one for the record books baby... I(‘)m good but holy f------g shit. Will tell you about it when there(‘)s more time. Hope you are well today,” Seyfried wrote.

Seyfried was also taking notes that day, at the urging of the union official, logging expired product he found on shelves:

“Found outdated milk on shelf throughout the day that I had not placed there,” he wrote.

The following day he apologized to his girlfriend.

“Sorry for the alarming text messages yesterday. It was a surreal day and my head was spinning. They are 100% going to fire me, I don’t know if I will make it financially,” Seyfried said. “I know this is a lot. But I love you very much.”

On March 6, Seyfried quit his job but tried to reassure those around him that it was for the best.

“Just calling to let you know I won’t be coming back to work,” Seyfried texted his coworker. “I’ve decided the best path forward is to make a clean break… I am… moving on with my life.”

But a day later, Seyfried’s calm resolve is gone. He sent texts to his girlfriend and a coworker where he appears confused about who he’s talking to.

“Hey what are you guys doing?” Seyfried wrote. “Amy and I have a personal relationship. This does not involve work. What is happening here is not right.”

And: “Who are you and how do you justify what you are doing?” Seyfried wrote. “I’ve stepped down and quit the company. This situation is very distressing to me and my family.

“Please stop doing this.”

Worker death shocks loved ones, coworkers

Seyfried’s family, girlfriend and coworkers said he kept most of his struggles to himself until the end. They were still putting together pieces after he died. His father only discovered Seyfried’s journal three months after his death.

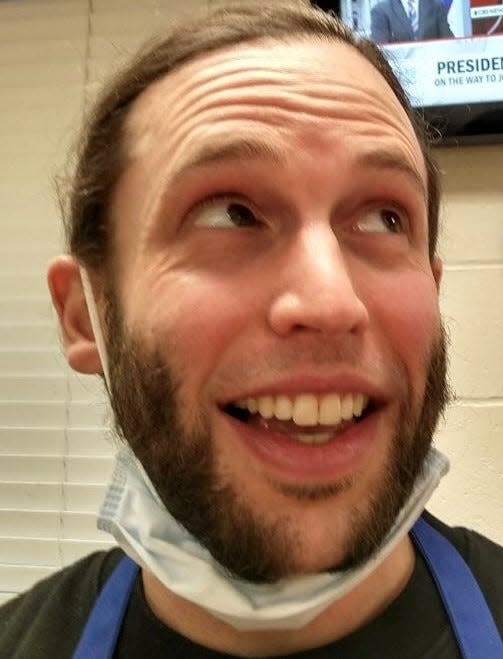

Seyfried’s brother Eric, 43, who lives in Portland, Oregon, said they talked all the time on the phone, but problems at work never came up. On the contrary, Evan had only just told him in the previous months that he was in love with his girlfriend. Things seemed to be going great.

“It was just shell shock when I first got the call from my dad,” Eric Seyfried told The Enquirer. “I just always expected my brother to be around… I miss him.”

Three weeks before his death, Seyfried told his father he was having problems with his management but didn’t give any details. Without knowing the specifics, the elder Seyfried urged his son to report all his work problems to his human resources department, Kroger’s ethics hotline and his union to create a paper trail. Later, when Ken Seyfried noticed strange cars during two of his son’s visits, his son refused to contact the police.

“We’re devastated – I’ve got a wife who not only lost her baby boy, she lost her best friend,” Ken Seyfried said, noting his son phoned his mother almost daily.

Chamberlin, 40, Seyfried’s girlfriend, said she believes Seyfried wanted to protect her from his troubles at work.

“He would talk about it like a little bit here and there, but it wasn’t enough for me to put all the pieces together,” she told The Enquirer. He mentioned his “Antifa” nickname. She also knew he was preoccupied in early 2021 with sexual harassment claims by coworkers against one of his store managers. He was unhappy with the “toxic” atmosphere at his store and she persuaded him to transfer to another.

But toward the end, he seemed relieved that he’d change stores soon.

Union officials with Local 75 of the United Food and Commercial Workers International say grievances and complaints have risen with the pandemic. They say they were working on getting Seyfried transferred to another store when he abruptly quit, then killed himself three days later.

While Seyfried’s texts reveal discussions with union officials, Local 75 say he didn’t file a formal grievance and he may have given more information to Kroger’s human resources department – but that information wasn’t shared with them.

“Evan Seyfried’s loss of life was tragic to his immediate family, the membership at his location and to the Local as a whole,” the union said in a statement.

Tracy Edwards, a 61-year-old meat clerk at the Kroger Marketplace in Anderson Township (another Cincinnati suburb) where Seyfried spent the first dozen years of his career, said he and several coworkers cried when they heard of his death.

“I thought the world of him… I wish he would have stayed with us (at the Anderson Township store) because he had so many friends,” Edwards said.

Kroger store manager: 'Not allowed to wear a mask'

Documents obtained by The Enquirer show Seyfried’s manager also clashed with another employee over masks early in the pandemic. Clermont County job coaches logged Frazee’s objections to mask-wearing and expressed concern about changes in how store management and employees treated the worker with autism.

The woman, 28, was promoted to a position in the Milford store’s bakery department for several weeks early in 2020, before she was “pushed out,” according to reports filed by her job coaches with the Clermont County Board of Developmental Disabilities.

On March 22, the store manager told the job coach “Kroger employees were not allowed to wear a mask because ‘How would that look for someone baking cookies to have a mask on(?) No one would buy cookies.’” the job coach wrote.

A month later, Kroger would require all employees to wear masks.

Two days later, a coach expressed concern for the changing work environment for the young worker.

“(She) struggles if her routine changes or if she gets pulled to do a different task. It almost seemed like (her supervisor) was trying to make it difficult for (the young woman),” the job coach. The coach continued: “(I’ve) noticed (the bakery and store managers) just don’t seem to treat (her) the same as everyone else.”

One example stood out that day: The store manager made a point of treating all the bakery workers to lunch, but snubbed the young autistic woman. The store manager “just walked away,” she wrote.

Two days later the young worker’s hours were cut.

“(I’m) getting the impression (she) is being forced out.” the job coach wrote.

Kroger lawyers: Ohio 'suicide rule' means 'defendants cannot be held responsible'

Kroger lawyers deny the allegations in Seyfried’s wrongful death lawsuit, but so far don’t discuss specifics. Instead, they have a powerful legal precedent they hope blocks any legal recourse regardless of what might have happened to Seyfried.

Civil liability ends with the “suicide rule” in most states, including Ohio. The precedent in Ohio was set by a suicide that coincidentally occurred exactly 38 years before Seyfried’s death.

On March 9, 1983, a 35-year-old man, Rene Morales, brought a 16-year-old girl back to his home, got her drunk and had sex with her. Despondent, the girl killed herself with Morales’ gun in his home. The girl’s family, named Fischer, sued Morales in civil court for wrongful death, arguing he knew the girl was depressed and that he had left her alone with a gun in his home.

An Ohio appeals court upheld the dismissal of the case in 1987. It ruled Morales wasn’t liable for the girl’s death because the plaintiff didn’t argue or prove Morales knew she was suicidal or put his gun in her hand.

Alex Long, a law professor at the University of Tennessee, said many states have similar precedents where in most cases a suicide victim is blamed for their own death regardless of what happened to them – or was done to them before taking their life.

“The legal cause of the suicide is the suicide (itself),” Long said of the legal thinking of most states. But he added courts in such states as South Carolina and Arizona have in recent years either ruled in favor of suicide victims or written legal opinions urging further consideration of circumstances leading up to a suicide.

Long also noted Ohio’s legal standard is “not as strict as most states.” In Ohio, a defendant can be held liable for someone taking their own life if the possibility of “suicide was reasonably foreseeable.” He added the defendant’s conduct would be examined to see if it “created an impulse” in the victim to take their life.

In court documents, Kroger’s legal team argues Seyfried’s suicide was not foreseeable, citing Fischer v. Morales at length. They do not discuss their clients’ alleged conduct in detail.

“The Kroger defendants could not have reasonably foreseen Seyfried’s suicide,” Kroger attorneys wrote. “The Kroger defendants cannot be held responsible.”

Back in Hamilton County Court, Kroger has moved to dismiss Seyfried’s case, citing Ohio’s suicide rule that has stood for 35 years.

The judge in Seyfried’s case is expected to rule on the motion sometime this fall. Seyfried’s family has vowed to appeal if their case is dismissed.

Kroger's $25 billion deal will add thousands of workers

In an odd coincidence, Kroger CEO McMullen may have met Seyfried at least once.

Seyfried’s old store in Anderson Township is near where McMullen lives and shops for his own groceries. The CEO has been known to check in with department heads and exchange a few friendly words with employees over the years.

McMullen famously worked his way through college studying accounting at the University of Kentucky as a Kroger stock boy. While Kroger’s slogan for customers is "Fresh for Everyone, its pitch for prospective workers alludes to that possibility of upward mobility: "Come for a job, stay for a career."

Seyfried was following that track when he left his job as a meat clerk at his first store to become a dairy manager. His death comes at a critical time for Kroger, which is struggling to get bigger and add workers amid a national labor shortage.

Kroger is hustling to bulk up as it battles tech titan Amazon, which moved into the grocery business when it took over Whole Foods in 2017. The Seattle-based juggernaut is only the latest non-traditional rival to turn to peddling cheap groceries to lure customers – and swamp traditional supermarkets already slogging through a saturated market.

Despite the cutthroat competition, Kroger figured out how to compete effectively and tripled its sales and added 50% more workers in the past two decades.

Kroger’s latest gambit: the $25 billion proposed takeover of rival Albertsons, an acquisition deal that would give the company more than 4,500 supermarkets in 48 states. Federal and state officials have expressed reservations but the company hopes to win regulatory approval in early 2024.

Kroger said the deal will be a winner for customers, shareholders and its workers.

A father's loss and disillusion

It’s been more than a year and a half since Ken Seyfried’s son died.

He is haunted by the fact that his son was trying to work within the system – and that he thought it would protect his son. After three decades at Ford, Ken Seyfried thought he understood how it would work at a major company like Kroger.

“I kept telling him to go to HR, they’ve got oversight systems to protect you, throw up red flags to get help,” Ken Seyfried said.

“To have a company like Kroger as big as they are with being what ended up no oversight systems whatsoever to protect my son… I can’t accept that,” he said. “I took it for granted that Kroger would take care of Evan, not target him.”

If you or someone you know is thinking about suicide, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org Service members and veterans who are in crisis or having thoughts of suicide and those who know a service member or veteran in crisis can call the Military Crisis Line/Veterans Crisis Line for confidential support 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. Call 1-800-273-8255 and press 1; text 838255; or chat online at VeteransCrisisLine.net/Chat.

For the latest on Kroger, P&G, Fifth Third Bank and Cincinnati business, follow @alexcoolidge on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Father says Kroger managers drove his son to suicide

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies