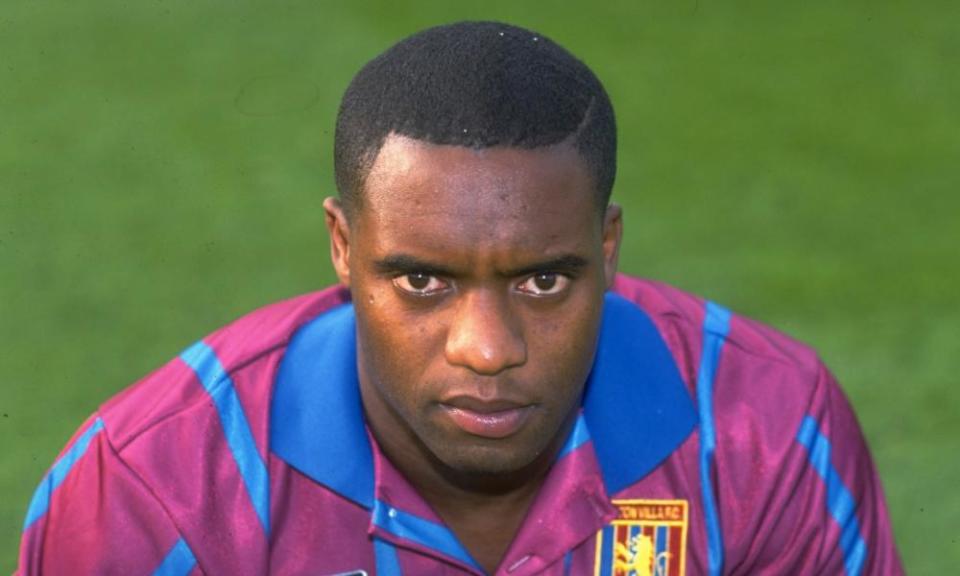

The killing of Dalian Atkinson: trial focused on a minute of violence

On his final day alive, Dalian Atkinson felt trapped. Draining physical challenges, from hypertension and kidney disease, had left him weakened and his mental health was crumbling, the jury heard.

He had once thrilled tens of thousands of people in football stadiums in England, Turkey and Spain. Now he was causing concern to two of those closest to him: his partner, Karen Wright, and Jonty, the friend whose house he was staying in.

As Sunday 14 August 2016 progressed, Atkinson prophesied his own death. “He was quite convinced he was going to be killed,” Wright told the court, “either by the NHS or the police.”

She testified that on his final day, Atkinson said the “world is sock-shaped” and referred to himself as “the messiah”. It was the first time she had heard him use that term but it would not be the last.

He was calm as the day started in Telford, Shropshire with him preparing to go to a Cheshire hospital the next day for dialysis treatment for his kidney condition.

He was “chuntering” about the Professional Footballers’ Association, which was helping him with his treatment, he got a haircut and talked to one of his brothers on the phone.

As the day went on, Atkinson pulled out a line fitted for his dialysis, exclaiming: “I’m free.”.

Then came the decision, possibly impulsive, that had dramatic consequences. When he was wealthier, Atkinson had bought a home in Meadow Close, Telford, where his father, Ernest, now lived. By evening, he wanted to go there, saying he wanted to “go home”, the jury heard.

His partner tried to stop him, as did his friend. They squared up to each other, then made up with a hug.

Atkinson insisted, and just before 1am he took his partner’s Porsche and drove to Meadow Close, where he kicked a football as a child on his way to becoming a prince in the footballing world. Within an hour, he would lay dying on the street.

Ernest, then 85, said in his court statement that his son had last visited three days earlier with his brother Paul who had accompanied him after his dialysis. Atkinson had then seemed normal.

That night, at about 1.10am, Atkinson asked his father if he could come in. He seemed upset and pounded on the front door. He came in, and according to the statement: “Dalian told Ernest that he loved him. Dalian asked why his father and the rest of the family were trying to kill him.”

Atkinson said: “I’m alive. I’m the messiah and I’ve come to kill you.” Then: “Dalian described himself as a born-again Christian. It seemed to Ernest that Dalian was angry, and in particular angry with himself.”

At one point, he grabbed his father by the throat, then there was a lull. Neighbours were getting concerned. Hearing the noise, one called Ernest’s landline, Dalian answered, and again said he was the messiah. Ernest said he “had never seen his son like that before”.

At this point the police knocked at the door, after a concerned neighbour had called them.

PC Benjamin Monk had been a police officer for 12 years with the West Mercia force. The court heard that he grew up in Bridgnorth, Shropshire, and his father had been in the Royal Air Force. He had an older sister and gained a sports science diploma from Shrewsbury College.

Aged 22 in 2002, he joined West Mercia police. By 2010 he was authorised to have a Taser and served in the force’s operation support unit, and told the jury that meant mainly dealing with traffic issues. By 2013 he was a frontline officer based in Telford. He married in 2007, with a daughter born in 2009, but by 2011 his marriage had ended in divorce.

On the night of Atkinson’s death in August 2016, he was on a night shift with probationary officer PC Mary Ellen Bettley-Smith. The court heard they were in a relationship at the time, which had begun in 2015.

Monk knocked on the door in Meadow Close and Atkinson came out. What followed was a clash with Atkinson that lasted six minutes. The prosecution said that for the first five minutes Monk’s actions – as he dealt with the erratic and bizarre behaviour of Atkinson – were lawful.

It was the final minute, with its prolonged stun gun use and kicks to the head, that led to a historic guilty verdict against a British police officer. Jurors heard Monk’s actions described as multiple kicks or stamping. One officer recalled seeing Monk with his boot resting on the head of the dying man, as if Atkinson was now his trophy. Another recalled Monk telling him immediately after that he “had to kick him in the head”.

The issues in the trial at Birmingham crown court boiled down to two.

Did the force used by Monk kill Atkinson? Some experts who testified said that despite Atkinson’s health problems – including a heart so enlarged it was 50% bigger than normal – the force used did contribute to his death.

The second issue was whether Monk was acting in self-defence when he used his stun gun for 33 seconds and kicked Atkinson in the head.

Monk said the kicks, which he had initially not admitted to, were because he feared Atkinson, after being shot with the stun gun, would get up and kill him.

For the prosecution to get the guilty verdict against Monk that it secured on Wednesday, it had to prove beyond reasonable doubt a number of issues to the jury.

These were set out by trial judge Melbourne Inman QC, the recorder of Birmingham, in his legal directions to the jury before they started deliberations.

Monk was arguing the force he used was in self-defence and he had a right to act in the way he did.

The judge said: “If someone, including a police officer, is under attack or believes that he or someone else is about to be attacked or that a crime is about to be committed or there are grounds to make an arrest, then that person is entitled to use force to defend themselves or others or to prevent a crime or to make an arrest so long as they use no more than reasonable force to do it.”

The judge continued: “As a police officer, Mr Monk was required to take all steps that reasonably appeared to him to be necessary for preventing crime and protecting the public and was therefore entitled to use force so to do as long as he used no more than reasonable force to do it. What amounts to reasonable force in the circumstances is a matter for you.

“How do you decide what force is reasonable? Firstly, the question whether the degree of force used by Mr Monk was reasonable in the circumstances is to be decided by reference to the circumstances as Mr Monk believed them to be, even if Mr Monk was mistaken about the circumstances and whether or not the mistake was a reasonable one for him to have made.

“So, for example, even if Mr Monk was mistaken that Mr Atkinson was trying to get up, but he genuinely believed that he was, you must decide the reasonableness of his actions by reference to the circumstances of his mistaken belief.

“Secondly, in deciding that issue you must take into account that a person acting for a legitimate purpose may not, in the heat of the moment when fine judgments are difficult, be able to weigh to a nicety the exact measure of any necessary action.”

The jury, after methodical and careful consideration of the evidence over nearly 19 hours spanning six days, decided the force used by Monk was not lawful and found him guilty of manslaughter.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies