Khalid Sheikh Mohammed confessed to being the 9/11 mastermind. 20 years later, he’s still awaiting trial

For the past 20 years, I have been chasing a ghost – the man who single-handedly masterminded the attacks on New York and Washington and launched an American war against terrorism that continues to this day.

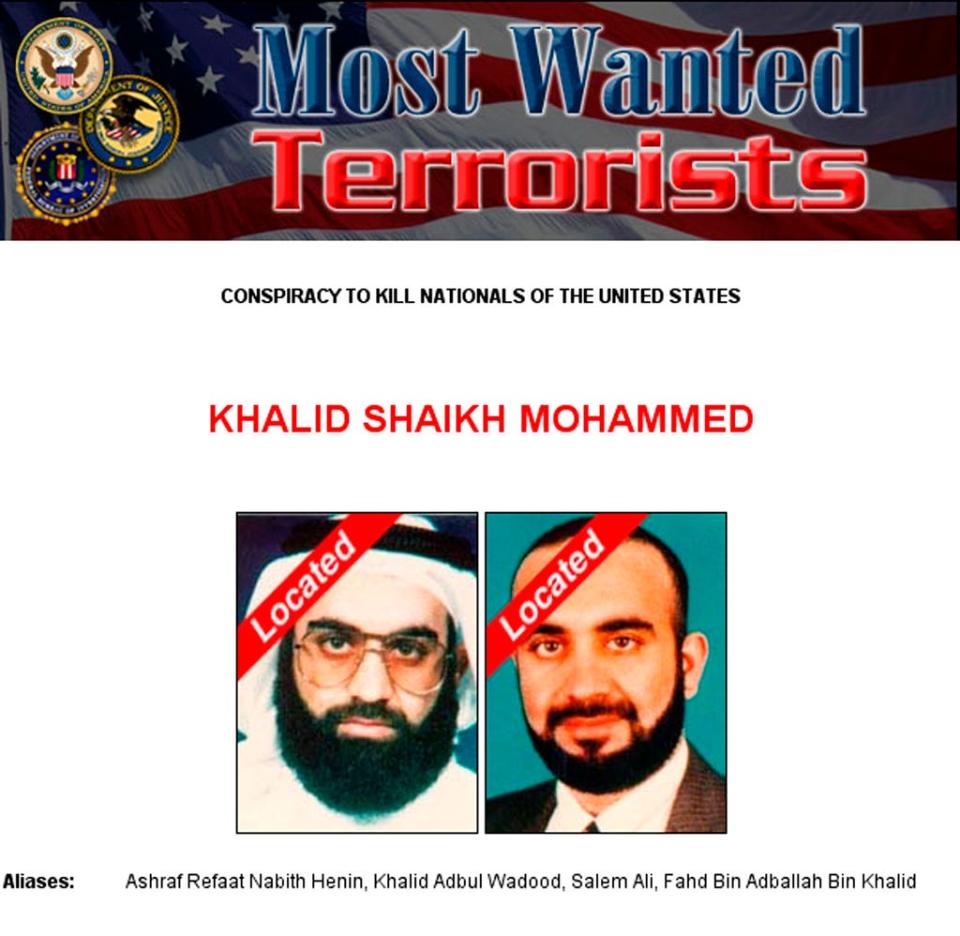

His name is Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, and he is the U.S.-educated Pakistani engineer who, as the operational commander of al-Qaida, also orchestrated dozens of other terrorist plots and attacks against Americans and other innocents around the world.

Yet since his capture in 2003, Mohammed has been kept hidden away by a U.S. government that claims to want to bring him to justice but never has. As a result, what he did – and, importantly, why he did it – remains largely unknown to the public except for some broad-brush details.

Now, Mohammed – or KSM as he is commonly known – stands at the epicenter of the most vexing questions and conflicts that have arisen during our modern age of terror that began on that blue-sky September morning.

Chief among them: Can someone who the U.S. government has admittedly tortured ever be fairly tried, convicted and sentenced to death for crimes he admitted under duress?

Can the most consequential act of terrorism known to mankind be prosecutable under U.S. laws that have existed since our nation’s inception? Or were the 9/11 attacks so monstrously transcendent of societal norms that their perpetrators can simply be secreted away without ever having the opportunity to contest the accusations against them?

Will the United States, a nation that prides itself on its foundations of democracy and the rule of law, ever bring Mohammed to justice? And what does it say about America that it can't lay out its case publicly for the world – and the survivors of the nearly 3,000 victims – to see?

At the end of the second World War, a U.S.-led coalition charged, prosecuted, convicted and executed the top leadership of Nazi Germany within two years of the cessation of hostilities. At the outset of the Nuremberg trials, chief U.S. prosecutor Robert Jackson gave a soaring oration about the grave responsibility of devising and conducting the first trial in history for “crimes against the peace of the world”:

The military tribunals that followed, according to most observers, produced a fair, transparent and just result – and a vast body of publicly available evidence for the annals of history.

I have thought often of Nuremberg and Jackson’s remarks since early 2002, when I first began trying to anticipate what the U.S. government would do with 9/11 suspects.

Since then, I have pursued Mohammed to nearly every continent on the globe and, ultimately, to the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay where he still awaits trial for the deaths of nearly 3,000 people.

A GHOST EMERGES IN PAKISTAN

Six months after the 9/11 attacks, an FBI agent told me a shocking – and highly-classified – secret in a pub just blocks from the still-smoldering World Trade Center wreckage.

At the time, the entire might of the U.S. military and intelligence machine was focused on finding Osama bin Laden, the al-Qaida leader whose claim of responsibility had made him the public face of the worst terrorist attacks of the modern era.

But the agent, attending a retirement party for one of his international terrorism squad colleagues, confided that the FBI had learned about someone else who might be far more personally responsible than bin Laden for virtually every aspect of the attacks. And agents believed the man was orchestrating many other operations around the globe, some of them imminent.

After much pleading on my part, the agent looked this way and that to make sure his colleagues weren’t listening, bent toward me and murmured the man’s name: Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.

Within hours, I was calling sources at the highest levels of the U.S. government, including a senior White House national security official. He insisted – falsely, it turns out – that he’d never heard of a man by that name, or anyone else with a central role in the attacks.

I kept digging. Because I had spent the year before 9/11 covering the growing threat posed by al-Qaida on U.S. soil, I had developed a good understanding of how the terrorist network operated on the global stage. I also knew first-hand how the U.S. government had been trying – with some success – to unravel it using the same criminal investigative strategies that the FBI and Justice Department had developed over many decades.

That previous summer, for instance, I had watched in a Manhattan courtroom as prosecutors persuaded a jury to convict some of the al-Qaida foot soldiers who blew up two U.S. embassies in Africa in 1998. The blasts killed 224 people, including 12 Americans, and wounded more than 4,500 others. It was quick, on-the-ground FBI gumshoe work that sent the defendants to prison for many lifetimes.

And I had interviewed dozens of FBI agents, Justice Department prosecutors and White House officials involved in the Millennium Bomber case. That resulted in criminal convictions for an Algerian-born Canadian named Ahmed Ressam and two cronies who had plotted to blow up Los Angeles International Airport at the turn of the century the year before.

One FBI agent had logged 400,000 flight miles and learned French in order to build that case. Like his counterparts investigating the Africa embassy bombings and the 2000 attack on the USS Cole warship in Yemen, he had bagged and tagged evidence and obtained incriminating statements that proved essential in numerous criminal investigations.

In each of these, prosecutors and agents laid out a meticulously documented case against the accused. Their lawyers fought tooth and nail to make sure the process was fair and transparent. I remember thinking this was the American system of justice at its best.

GATHERING EVIDENCE – AND DETAINEES

The 9/11 attacks, though, basically threw that system out the window. In the frenzied aftermath, the gloves came off, as then-Vice President Dick Cheney would so famously say. And the Bush administration took the international counter-terrorism portfolio away from FBI agents and federal prosecutors and gave it to the CIA and the Pentagon.

That was why American spies and soldiers had toppled the Taliban, al-Qaida’s protectors in Afghanistan, and bombed bin Laden’s suspected mountain redoubts. That made sense, given that the wily Saudi recluse was believed to be holed up with a security phalanx of dozens or even hundreds of heavily armed fighters.

The FBI's involvement in 9/11 began as a search and rescue mission, with its Strategic Information and Operations Center providing multi-agency analytical, logistical and administrative support for the teams on the ground in New York, Pennsylvania and at the Pentagon.

The crash sites soon became crime scenes, and the tedious process of evidence collection became one small facet of an expanding global criminal investigation. The FBI dubbed it PENTTBOM, combining the Pentagon with two T's in honor of the trade center’s Twin Towers.

The FBI’s new director, Robert Mueller, was on the job only a week when the 9/11 attacks occurred, but he immediately deployed agents to Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and other al-Qaida operational hotspots.

I soon followed. And thanks to introductions made by some of the bureau’s elder statesmen – and they were all men – I spent time with some agents at the center of the fast-expanding investigation.

By early June, I had enough information to publish a story about KSM and the secret U.S. effort to apprehend him.

The hunt for Mohammed was by then a guns-drawn law enforcement pursuit of a criminal suspect through the streets of Pakistan’s major cities. Two of the agents who had led the Africa embassy and Cole bombing investigations were even the ones who got a senior al-Qaida supporter to cough up KSM’s name while questioning him in a hospital bed near Lahore.

The FBI helped catch one KSM associate after another. But each one was quickly handed over to the CIA, which put them on jets headed for its new archipelago of overseas “black site” prisons.

When Mohammed himself was finally caught in the Pakistani military garrison city of Rawalpindi in March 2003, the CIA took custody of him too. Like other suspected senior al-Qaida operatives, he was brutally tortured by CIA contractors in an effort to obtain information about future attacks.

KSM was waterboarded 183 times, and subjected to other “enhanced interrogation” techniques, as the Bush administration euphemistically called them, according to a Senate report on the CIA torture program. Those included “facial and abdominal slaps, the facial grab, stress positions, standing sleep deprivation (with his hands at or above head level), nudity, and water dousing.”

He was also subjected to rectal rehydration “without a determination of medical need,” in order to demonstrate “total control over the detainee.” Mohammed, all of 5 foot 4 inches, quickly lost more than 50 pounds, or a third of his body weight.

The torture sessions occurred over a matter of just a few weeks. But Mohammed and the others were milked for information in CIA prisons until September 2006, when President Bush announced – with much fanfare – that they were being transferred to Guantanamo Bay for trial before military commissions.

A SLEW OF CONFESSIONS, ADMISSABILITY DEBATED

By the time the 14 suspects touched down on Cuban soil, the tribunals were already a complicated and controversial mess.

Defense lawyers appointed to represent the men immediately seized on the CIA torture as proof that Mohammed and the others could never receive a fair trial. It didn’t matter that KSM had gleefully boasted to a reporter – months before his capture – that he had orchestrated the 9/11 attacks. And it was inconsequential, they said, that Mohammed claimed in an early Guantanamo court appearance that he was responsible for September 11th “from A to Z.”

None of Mohammed’s confessions mattered, defense lawyers said, because they initially had been obtained during CIA torture sessions.

At his March 10, 2007 hearing, Mohammed claimed leadership of at least 31 terrorist attacks as “Military Operational Commander for all foreign operations around the world under the direction of Sheikh Usama Bin Laden and Dr. Ayman Al-Zawahiri.”

Mohammed then proceeded to “admit and affirm without duress” a litany of other plots and attacks. He bragged that he was responsible for all planning and training of the 19 hijackers, including teaching them how to use English catch phrases, Internet chat rooms and American phone books so they could operate under the radar in the United States. He also had them slaughter sheep, goats and camels so they wouldn’t flinch when slashing the necks of airline pilots and crew.

He said he was “directly in charge” of al-Qaida’s biological weapons program, including the production of anthrax and dirty – or low-level radiological – bombs. He claimed responsibility for the 1993 World Trade Center attack, for which his nephew Ramzi Yousef had been tried, convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

And Mohammed said he engineered the December 2001 “Shoe Bomber Operation” to down two American airplanes, and the 2002 bombing of a Bali nightclub that killed 202 people, including seven Americans. He was responsible, he said, “for planning, training, surveying, and financing” the so-called Second Wave of suspected post-9/11 plots to take down America’s tallest skyscrapers, including the Library Tower in Los Angeles, the Sears Tower in Chicago and the Empire State Building in New York City.

Almost as an afterthought, Mohammed also claimed responsibility for leading operations to destroy American military vessels and oil tankers in key waterways, to blow up the Panama Canal and to assassinate several former U.S. presidents, including Jimmy Carter.

He made so many claims, in fact, that the FBI agent who spent most of his career chasing Mohammed would later joke that he would take credit for the bombing of Pearl Harbor if he thought he could get away with it.

Investigators later came to believe Mohammed was so expansive in his claims because it took the focus off others who remained at large and plotting attacks. FBI agents were sent on dozens of false alarms and wild goose changes, officials told me.

But many of Mohammed's claims were true, and backed up by evidence that the FBI seized in raids in Pakistan and elsewhere, including a computer found when he was captured.

There was one confession of Mohammed’s that day that hit home on a deeply personal level.

“I decapitated with my blessed right hand the head of the American Jew, Daniel Pearl, in the city of Karachi, Pakistan,” Mohammed said during the marathon hearing. “For those who would like to confirm, there are pictures of me on the Internet holding his head.”

I had met Pearl, the South Asia bureau chief for the Wall Street Journal, and was in Pakistan talking to some of the same jihadist sources that he was when he was abducted from a Karachi restaurant. Danny was ultimately handed over to KSM, who had an associate videotape him decapitating the handcuffed reporter with a butcher knife.

I had declined a similar invitation to meet with some of those same sources at another restaurant in Pakistan at around the same time while reporting out a long profile of KSM. I have thought often about how easily it could have been me that Mohammed boasted about killing.

THE MAN WHO MADE KSM HIS MISSION

Behind the scenes, the FBI had been quietly working to salvage the cases against the 9/11 defendants by sending so-called “clean teams” to Guantanamo to re-interview the five men and extract new – and unforced – confessions from them.

The heart of the case against KSM would ultimately consist of admissions he made in 2007 to Frank Pellegrino, a former accountant and lawyer turned FBI agent who had been chasing him since the 1993 investigation into the first World Trade Center bombing.

For much of the 1990s, Pellegrino and partner Matthew Besheer had followed Mohammed’s peripatetic trail across Asia, the Middle East and even Latin America. They crawled through the jungles of the Philippines and interviewed his friends and prostitute consorts. They spent weeks at a time wiretapping his suspected associates using old-fashioned tape-recorder microphones stuck to the floors of hotels so they could capture the conversations from the room below.

Pellegrino had even obtained a federal indictment against KSM in 1996, in part by gaining possession of a water glass with his fingerprint on it in Qatar and ferrying it back to New York in an evidence bag so a grand jury could examine it.

Like other FBI counter-terrorism agents before 9/11, Pellegrino did not have the option of taking out KSM with a drone strike or simply seizing him, like the CIA could after the attacks. Instead, in 1996, the FBI had to ask the Doha government for help in arresting Mohammed. And when agents were about to move in, he was tipped off by Qatari authorities and eluded their grasp.

The next time Pellegrino thought of Mohammed was when the two planes hit the World Trade Center. It was so similar to KSM's mid-1990s plot to plant bombs on 11 jetliners flying from Asia to the U.S. that the agent knew it was him. And Pellegrino was the first person FBI agents called when they realized that the 9/11 mastermind they'd just learned about was the same man that he had been pursuing until the CIA took over the case.

In early 2007, thirteen years after undertaking his pursuit of the elusive terrorist mastermind, Pellegrino was told he would finally get his chance to sit face-to-face across a table from KSM. He studied his own voluminous case files and the more recent ones compiled by various U.S. agencies. And on a sunny and bright afternoon, Pellegrino met KSM across a gray metal government-issued table in a makeshift cell in Guantánamo.

Pellegrino was accompanied by an analyst from FBI headquarters who had worked on the case nearly as long as he had, and two agents from the Pentagon’s Criminal Investigative Task Force.

It seemed all of Guantanamo was buzzing in anticipation. Everyone had heard the stories by then of how the agent had chased the terrorist around the globe only to be kept out of the hunt for him after 9/11. Observers crowded into the small room housing the closed-circuit TVs so they could watch, expecting to see some dramatic confrontation. It never occurred.

Instead, Pellegrino used traditional FBI interrogation procedures to slowly establish a rapport with his longtime nemesis. He opened by saying he had been following Mohammed in Pakistan and Manila before trying to arrest him in Qatar.

“Ah, so you’re the one,” KSM responded, adding that he had known when the FBI agent had arrived in Qatar and even the name of the hotel where he was staying.

At the end of their sessions, Pellegrino would later tell me, he had come to believe the charismatic KSM might be the kind of guy you could sit down and have a beer with, if he hadn’t been one of the worst mass murderers in history. He also got Mohammed to confess to his crimes.

CHOKING ON LEGAL CHALLENGES

The FBI continued to quietly reconstruct the cases against KSM and his four alleged associates, spurred in part by concerns that years of CIA interrogation had yielded evidence that was either inadmissible or too controversial to present at their upcoming war crimes tribunals.

Now, the bureau was trying to salvage any kind of prosecutions at the discreet request of the Department of Defense.

In October 2007, I disclosed that top-secret effort in a story detailing the problems, one of which was confronting the bedrock American legal principle of allowing defendants to face their accusers in court. Not surprisingly, the CIA wasn't going to permit its case officers to reveal their identities, no less take the stand to face cross-examination about their interrogation techniques and other highly classified aspects of the spy agency's detainee program.

"They have put themselves in a very bad situation here,'' one former FBI agent told me at the time. "They have to come up with clean statements from these [detainees], if they can get them, obtained by law enforcement people who can actually testify. The CIA agents are not going to testify, nor should they.''

Federal law enforcement officials, however, told me that they believed they had gathered enough admissible evidence to try the high-value detainees.

"We've redone everything, and everything is fine,'' one official said. "So what's the harm?''

But everything was not fine.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

It wasn’t just that the CIA interrogations of the men could be ruled inadmissible. Another problem was that the CIA operatives had interrogated KSM and the other suspects for the sole purpose of gathering intelligence to stop future attacks, as opposed to building evidence-based cases that could stand up in a court of law — even a military one.

And even if the information from the CIA interrogations were allowed, the FBI and Pentagon believed it would likely risk focusing the trials on the actions of the spy agency and not the accused.

"People like KSM should be held accountable,” Amnesty International’s Jumana Musa told me at the time. “And the real tragedy would be that the focus of the commissions won't be on scrutinizing the conduct of Mohammed and the others, but on the conduct of the CIA.''

Another key issue is whether computer data and other evidence obtained during joint U.S.-Pakistani raids was preserved under traditional FBI “chain of custody” procedures that account for the integrity of a sample by tracking its handling and storage from the point of collection to final disposition.

“We had it showing up in garbage bags, nobody knows where it came from, who handled it, what happened to it, until the FBI gets hold of it sometime later in the process,” said James G. Connell, one of the longest-serving defense lawyers for the 9/11 defendants. “If they had done it law enforcement style, it would be an easy case to prosecute. But since they did it, you know, rough justice style, it becomes a much bigger and more difficult case to prosecute.”

It took another four years for the 9/11 defendants to be arraigned on charges of murdering 2,972 people in the 2001 attacks.

By that time in March 2012, I'd co-authored a book on the FBI’s hunt for KSM, and I was able to go to Guantanamo as a special observer. That observer status afforded me privileges that wouldn't have been extended to me as journalist, including the ability to sit in the courtroom for the entire proceedings.

During one break, KSM stood, looked back and made sustained eye contact with me. His face betrayed no emotion of any kind, but his stare was penetrating. Finally, I smiled and raised my arms to my sides with cupped hands facing up. “Why did you do it?” I asked, accentuating the words so he could lip read them. He gave no response.

Later, I asked his legal team if the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks knew who I was. Of course, they said. And he’d already read the book.

Despite facing the death penalty for their roles in the Sept. 11 attacks, Mohammed and an alleged accomplice told the presiding judge at an earlier hearing that the military commission process was completely dysfunctional. They could not even file legal motions in their defense, they said, or have pretrial documents translated into their native languages.

In separate hearings, Mohammed and Walid bin Attash and their legal advisors ticked off one example after another of a pretrial system that they said was barely operating. "We are not in normal situation. We are in hell," Mohammed told the military judge, Marine Col. Ralph H. Kohlmann, in his broken English.

NO END IN SIGHT

That arraigwas nine years ago, and things have gone downhill since. At least four judges have come and gone. Key prosecutors and defense lawyers have either retired or moved on, some out of sheer frustration.

Each one of those transitions has prompted even more delays and legal clashes.

This week, on the 15th anniversary of their transfer to Guantanamo, and the 20-year mark of the 9/11 attacks, KSM and his co-defendants have been back in court yet again for the kind of pre-trial motions often heard in the initial days of a major prosecution.

The hearing on the qualifications of a new judge, Air Force Col. Matthew McCall, was the 42nd round of pretrial hearings since the arraignment in May 2012.

Defense lawyers are objecting to literally dozens of issues that they say would deprive their clients of a fair trial – and the American public of the transparent, just and legitimate verdict that they deserve.

Carie Lemack, whose mother died on the first plane to hit the World Trade Center, has also followed KSM’s legal odyssey from the outset.

“Family members of most murder victims do not have to wait 20 years or more after the crime to have a trial of those accused of the crime,” Lemack, who has advocated tirelessly on behalf of the 9/11 families, told me this week. “The wait is painful and seemingly never-ending, as new roadblocks emerge one after the other.”

For his part, Pellegrino fought off mandatory retirement for years, he told me, because he wanted to have the full weight of his FBI authority behind him when he finally testified against Mohammed in court. Ultimately, he couldn’t beat the clock, and turned in his badge and gun last December.

“It breaks your heart” that justice has not been delivered in the case, said Pellegrino. "There are family members who lost loved ones and now they're dying off and they've never seen this come to an end."

Connell said if the detainees had been taken to a U.S. court, the "case would have been over 18 or 19 years ago."

"The core answer to why the (Guantanamo) prosecution takes so long is that the United States departed from its ordinary criminal justice model,” Connell said. “We abandoned the justice system as a way to deal with people suspected of serious crimes. And then that had a lot of consequences afterwards.”

President Barack Obama tried to move the trial to the Southern District of New York in 2009 and was shot down by Congress, citing security and financial considerations. President Joe Biden, like his Democratic predecessor, has suggested support for Guantanamo's closure, but when press secretary Jen Psaki was asked in July, she said "I don't have a timeline for you."

More than a dozen people involved in the process told me this week that it could take another decade for the self-admitted mastermind to face justice. And if defense lawyers have their way, one told me, there will never be a trial at all.

“The military commissions were doomed to failure from the very start. It was nothing but arrogance to have the government believe that they could create a whole new legal system from whole cloth, with new rules and regulations and procedures to try the most notorious defendants in modern history,” said Anthony Romero, the executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union. “And it’s the arrogance of the Bush administration that was inherited and continued by the Obama administration, that was put on autopilot by the Trump administration. And now we’ll see if the Biden administration has the courage of our convictions to shut down this failure for what it is."

Romero said the ACLU has spent almost $13 million on the legal defense of the 9/11 defendants because it believes the military commission system is inherently unfair. It lacks even the most basic due process protections afforded even minor criminal suspects in conventional American courts, he said.

Without a public prosecution and the display of evidence that requires, the American public is left guessing about key details of America’s worst-ever attacks — and about the man who so gleefully boasts about orchestrating them.

“If there was a trial, people could go back, look at the record and know what he did and how he did it. But when it gets pushed aside and kept away, it just gets forgotten. And that’s not right,” Pellegrino said. “It matters for us as a country that we don't just pick people up, say that they're guilty of a crime and then not follow through.”

Mark Fallon, the former head of the Guantanamo investigative task force, went further, saying that the post-9/11 system “violated the inalienable human rights America was founded upon” and that the Bush administration's treatment of detainees "amounted to war crimes."

It will also leave a lasting and potentially deadly legacy, he said, especially since the Bush administration extended elements of the CIA’s post-9/11 interrogation program to Guantanamo, Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison and other military detention facilities. By adopting the same kind of brutal tactics that dictators had used, he said, the U.S. government handed al-Qaida, the Islamic State and other terrorists a powerful recruiting tool that has created an entire generation of anti-American militants around the world.

“If you want to radicalize somebody, if you want them to really hate you, you torture them,” Fallon said. “How many tens of thousands of Islamic extremists have we created through the Gulag archipelago of our dark prisons?”

Josh Meyer is domestic security correspondent for USA TODAY and co-author of The Hunt for KSM: Inside the Pursuit and Takedown of the Real 9/11 Mastermind, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. Follow him on Twitter @JoshMeyerDC.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: 20 years after 9/11, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed still isn't convicted

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies