Kentucky coal company, official admit cheating on tests designed to protect miners

A Kentucky coal company and one of its employees have admitted to cheating on dust sampling meant to protect miners from debilitating black lung disease.

Black Diamond Coal LLC pleaded guilty to one charge of willfully violating a mandatory federal health and safety standard and one charge of making false statements about dust sampling.

Walter Perkins, who was in charge of sampling for dust in Black Diamond’s underground mine in Floyd County, pleaded guilty to a charge that he authorized, ordered or carried out a violation of a health and safety standard and to a charge of making false statements.

The plea by Black Diamond calls for the company to pay a fine of $200,000 and be placed on probation for two years if U.S. District Judge Robert E. Wier approves the plea.

U.S. Magistrate Judge Edward B. Atkins recommended Wier accept the plea.

The plea agreement for Perkins did not specify a particular sentence. He faces up to five years in prison on the most serious charge.

Coal companies are required to have designated employees at underground mines wear devices that record concentrations of respirable dust, meaning dust that can be breathed in.

The dust from coal and rock is created as machines dig into the working face of the mine to get out the coal.

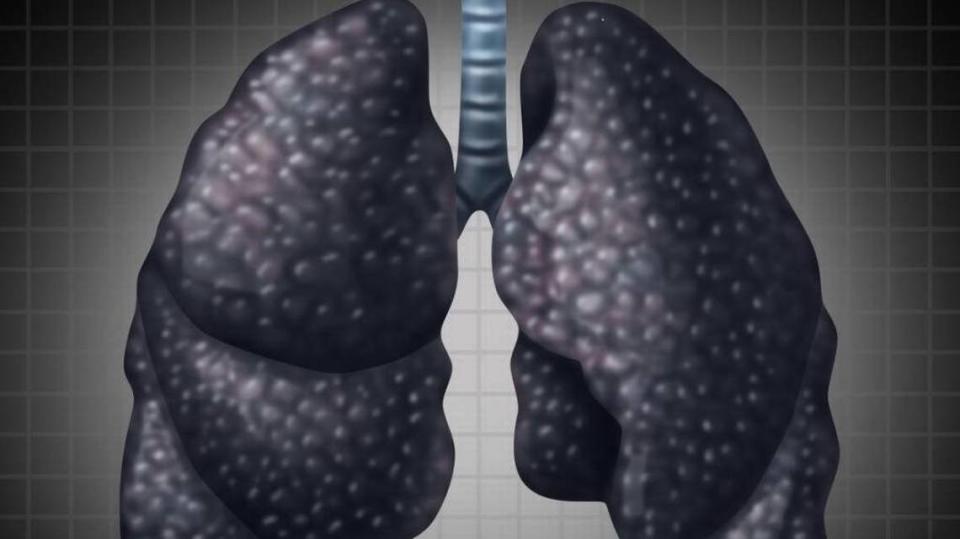

Breathing in coal dust is the cause of black lung, in which fibrous tissue forms in the lungs, choking off a person’s ability to breathe and often leading to premature death.

Dust sampling is intended to make sure miners are not being exposed to unsafe levels of coal dust.

On Oct. 8, 2020, inspectors from the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration caught Black Diamond and Perkins breaking the law on dust sampling, according to court documents.

The inspectors found a personal dust monitor — which was supposed to be on a mine employee underground — running in a trailer on the surface.

That meant it would record clean air, not the level of dust in the mine.

If dust levels are too high, coal companies must use ventilation or water sprays to reduce the levels, or even reduce or stop production, and can be cited for violations.

Perkins claimed to MSHA he had given the dust monitor to the operator of the continuous mining machine to wear underground, but the operator gave it back to him because it hadn’t worked properly, according to plea agreements.

However, an MSHA specialist ran a check on the machine and it showed it had no problems.

The dust monitor showed that it had been in temperatures of 70 or 80 degrees, far warmer than the temperature in the mine, and a function of the machine that records when it tilts or moves showed it hadn’t been moved the day the inspectors found it, according to the court record.

Perkins admitted he didn’t give the dust monitor to the miner operator to wear, his plea agreement said.

The company submitted data for Oct. 6 and 7 that it claimed was valid sampling data, but it didn’t show any level of dust in the mine for those days.

The continuous miner operator told investigators that Perkins had not given him a dust monitor to wear those days, according to the court record.

Black Diamond and Perkins were indicted in August and pleaded guilty Jan. 30 in federal court in Pikeville.

The prevalence of black lung dropped significantly after Congress approved new mine-safety rules in 1969, but started going back up around 2000, especially in central Appalachia, studies have shown.

One study published in 2018 said that 20.6% of miners in Eastern Kentucky, West Virginia and Virginia had black lung, four times the rate among miners elsewhere in the country.

Researchers have cited several possible reasons, including mining thinner seams of coal that produces more rock dust, but cheating on dust sampling has been identified as part of the problem.

Miners and others interviewed for a paper published in 2020 said that “negligent dust practices and fraudulent dust sampling have become commonplace in many Appalachian mines.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies