Some in KC’s least-white, lower income neighborhoods pay high prices for slower internet

A joint investigation by national news organizations The Markup and The Associated Press has found that Kansas City is one of the most inequitable cities in the U.S. when it comes to internet service provided by two major companies.

Areas of the city with fewer white residents and lower average household incomes are being served slower internet by AT&T and Earthlink than areas with more white residents and higher average household incomes, all while being charged the same monthly rate.

The report’s data shows that residents in Kansas City’s least-white neighborhoods pay as much as three times per Megabit per second as those in the whitest areas of the city.

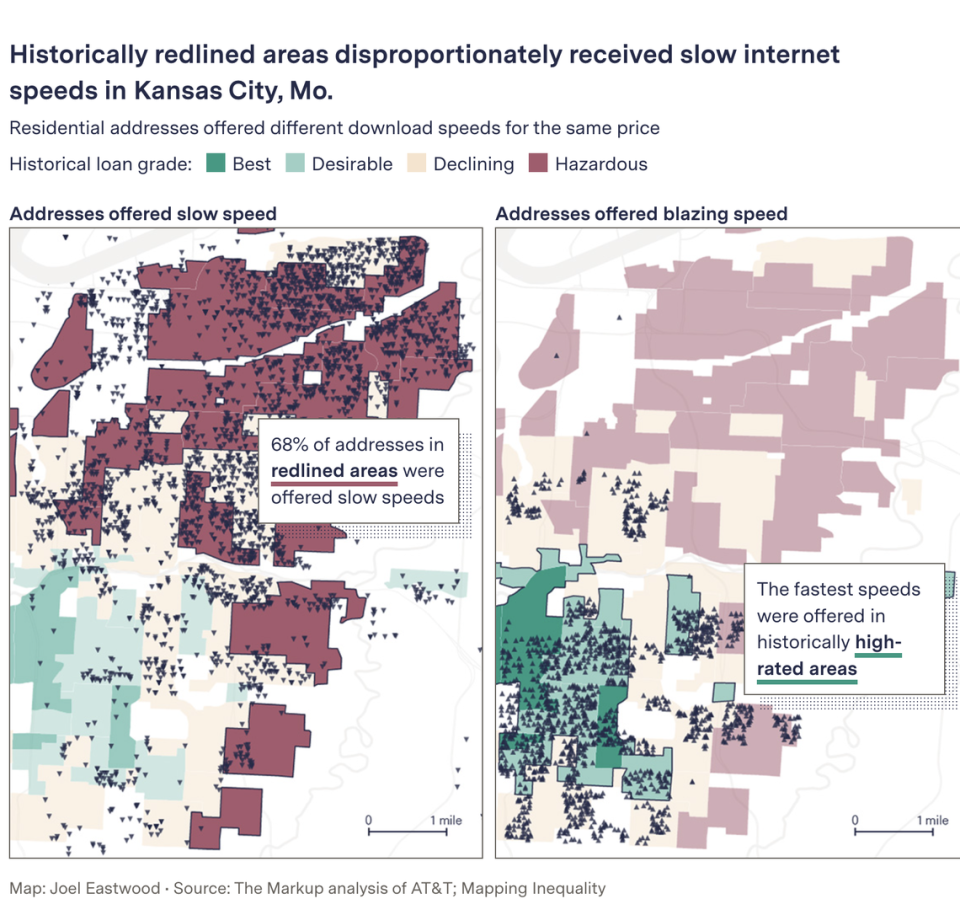

This trend was echoed around the country in 38 cities that the journalists analyzed. Disparities in internet speed echoed the shape of neighborhoods that were historically redlined in all 22 of these cities where digitized historical maps were available.

Reporters analyzed data from four providers nationwide, with only two active in the Kansas City area — AT&T and Earthlink. Other providers like Google Fiber and Spectrum were not analyzed.

How unequal is internet service in Kansas City?

The Markup’s reporters compiled data on the cheapest plans offered by Earthlink and AT&T to thousands of addresses around the metro. These providers were chosen for having some of the largest customer bases in the country, while also engaging in “tier flattening” or charging the same amount for different speeds, based on a preliminary random sample of addresses.

Reporters found that AT&T offers internet at speeds slower than the government definition of broadband to 54% of Kansas City’s low-income areas, but only 11% of high-income areas. That’s a margin of 43 percentage points, the second-highest disparity found among the 20 cities analyzed. For Earthlink, Kansas City’s margin for super slow internet is 27 points, the third-highest disparity between income groups.

Internet speed is often measured in Megabits per second (Mbps) — a unit showing how much information can travel through a customer’s connection in a given amount of time. The FCC’s definition of “broadband” internet includes download speeds at or above 25 Mbps. Below this speed, it’s difficult for internet customers to download large files quickly or make multiple video conferencing calls at once.

The disparity found in Kansas City was similar when neighborhoods were grouped by racial demographics. AT&T offers slow internet speeds below the federal definition of broadband to 50% of customers in the city’s least-white areas, but only 16% of customers in the most-white areas. That’s a margin of 34 percentage points, the second-highest racial disparity found among the 19 cities analyzed. For Earthlink, Kansas City’s margin is 26 points, also the second-highest racial disparity.

Co-authors Aaron Sankin and Leon Yin also broke down the thousands of addresses they studied into four quartiles: “least white,” “less white,” “more white” and “most white.” These categories were determined using data from the 2019 five-year American Community Survey on the racial makeup of neighborhoods around the city.

The graph below shows how the download speeds of the cheapest available plans in Kansas City vary across these racial categories for Earthlink and AT&T.

The investigation found that Kansas City internet customers are often charged the same for service regardless of its speed— causing those in less-white neighborhoods to pay more per Megabit per second. This disparity is shown on the graph below.

Kansas City also had the largest internet speed disparity of any city studied when neighborhoods were grouped based on their letter grades under historical redlining maps. This map shows how slow download speeds are largely found in areas that were redlined, while higher-rated areas have faster download speeds today.

“Kansas City, Mo.’s Troost Avenue is both a historical dividing line for racial segregation and an obvious inflection point separating a big cluster of fast connections from a big cluster of slow ones,” wrote coauthors Sankin and Yin.

AT&T denied any allegations of discrimination, calling The Markup’s report “fundamentally flawed” and pointing to the company’s own financial assistance program. Earthlink did not reply to The Markup reporters’ requests for comment.

Take a look at how plans in your area compare to the rest of the city on this map of AT&T’s service and this map of Earthlink’s service compiled by the reporters.

Why is internet service slower in some parts of Kansas City than in others?

The main thing that determines internet speed in a given neighborhood is infrastructure: That’s the physical wires, cables or other conduits that information travels through to get to your home. Common types of internet infrastructure include:

DSL and dial-up, which are delivered through existing telephone lines

Cable internet, which is delivered through the coaxial cable that your TV service comes through

Mobile and satellite internet, which get service beamed from satellites orbiting the Earth

Fiber internet, the newest type of service which uses underground fiber-optic cables to transmit huge amounts of information extremely quickly

Different internet providers can have multiple types of infrastructure in the same city. For example, the FCC’s Broadband Map shows that the block of Kansas City containing the Federal Reserve Bank has access to AT&T Fiber internet service with download speeds of 1,000 Mbps. Just two blocks east, AT&T’s only offering in a residential area of Union Hill is its DSL service at 100 Mbps, or just one-tenth the download speed offered a short walk away.

So, with the same company in the same city, you could be offered slower internet because the infrastructure in your neighborhood may be slower than in another neighborhood.

The speeds available often depend on where internet providers choose to develop fiber networks, which involves digging and physically installing new fiber cables in the ground rather than using existing phone or TV wires.

The Markup’s investigation found that many Kansas City households in lower-income or less-white areas are not offered super-fast fiber service.

City spokesperson Melissa Kozakiewicz told The Star that’s because providers are unwilling to invest in that infrastructure for those areas.

“ISPs are hesitant to make the investment because of the lower income community customer base,” she wrote in a message to The Star. “Where ISPs invest in building the infrastructure… the cost effect trickles down to the customer.”

She added that she is not aware of any city regulations on where or how internet providers need to distribute their service.

Internet service is not typically considered a utility, which gives governments less control over how it is distributed.

“Broadly, internet service is not currently regulated to the degree that telephone or cable service is,” said Sankin, one of the co-authors of the report.

But infrastructure alone isn’t the only thing that can affect internet speed, which can make things a bit more complicated.

“The infrastructure in Kansas City, by and large, is really quite good,” said Aaron Deacon, the managing director of KC Digital Drive, a nonprofit focused on expanding internet access in the metro. “Even in some of the poorer ZIP codes, we have a surprising amount of commercial fiber access available.”

Deacon explained that sharing service with your neighbors in a multi-unit building can still cause slow download speeds, and the quality of home equipment like wifi routers can impact residents’ service as well. These factors can cause slow internet connections even in homes connected to a fiber network.

Other providers may shift the landscape

The Markup’s investigation only collected data on four large internet providers: AT&T, Earthlink, CenturyLink and Verizon. That means that other local providers like Google Fiber and Spectrum weren’t included.

Deacon told The Star that robust infrastructure around the city from these other providers has led to competition that, in his view, keeps prices pretty fair.

“You are at a competitive advantage if you’ve got three fiber providers at your address versus if you only have one,” he said.

While The Markup didn’t report on Google Fiber’s service specifically, a small sample of advertised speeds at addresses around the city suggests that the company charges lower rates for slower service — something AT&T and Earthlink often don’t do.

“From what I could see, the base plan in most locations was 1 gig for $70, but there were also some addresses that had the option of 100 Mbps for $30,” Sankin wrote in a message to The Star.

Anyone can look up the Google Fiber plans available at a given address on the company’s website. You can look up all the internet plans available to you by typing your address into the FCC’s Broadband Map.

Infrastructure isn’t the only barrier to internet in Kansas City

Beyond internet infrastructure, a lack of access to physical devices to get on the internet and knowledge of how to use them can make internet access less equitable, Kansas City digital advocates say.

A recent study by the nonprofit group KC Rising used 2019 American Community Survey data to map the areas of Kansas City where residents have laptops or personal computers at home. The report found “over 100,000 area households currently without broadband subscriptions and computer devices.” The lowest levels of home computer ownership are in Wyandotte County and on Kansas City’s east side.

Lack of knowledge about how to use digital devices like computers and tablets can prevent residents from participating in the digital economy. There’s also the issue of affordability: Even if a home has access to lightning-fast download speeds, this resource is worth little if residents can’t afford to access it.

To combat these barriers, many groups around the metro are working to improve digital literacy and help Kansas Citians pay their internet bills.

What to do about a high internet bill in Kansas City

Sankin, one of the reporters of The Markup’s investigation, said the best way to optimize your home internet service is to shop around using the FCC’s Broadband Map. Many customers in the Kansas City area have six or more options for internet service — keep in mind that “Alphabet,” at the top of the alphabetical list for many addresses, refers to Google Fiber.

“It’s pretty straightforward for someone to check out all their options and potentially get a better deal,” Sankin said.

If you have access to the internet at home but are having trouble paying your bill, a federal program called the Affordable Connectivity Program can help by paying up to $30 per month for you. You can learn more on the FCC’s website here.

Deacon’s group also connects residents to a shorter-term program for those experiencing temporary financial hardship. It’s called the Internet Access Support Program, and can cover your internet bills in full for up to six months.

More efforts to help Kansas Citians get online

Kansas City is home to a myriad of groups addressing various parts of the digital equity issue, from infrastructure access to digital education. One such group is aSTEAM Village, a city-funded initiative to build out fiber infrastructure and promote computer literacy for teens and adults.

“We’re not just getting internet service to people. We’re more concerned with information and getting people into the digital economy,” founder William Wells told The Star.

His organization also offers free computer classes to residents hoping to enter careers in tech. The initiative is currently operating in the city’s Third District, but has plans to expand in the coming years. By focusing on one of the city’s lowest-income areas, Wells hopes to get broadband access and education where it’s needed most.

“We’re trying to put people in a position to be able to do their own fishing,” he said. “Once you can participate in the digital economy, where you live doesn’t matter.”

Other groups that help residents access the internet include the Missouri Department of Economic Development’s Office of Broadband Development, the Mid-America Regional Council, KC Rising, the UMKC Digital Equity Working Group and the 70 member groups of the Kansas City Coalition for Digital Inclusion.

“There’s a lot of room for a lot of people to help educate and support along the way to bring full-scale, high-speed internet to the state of Missouri and to Kansas City,” said Alison Copeland, deputy chief engagement officer for the University of Missouri system.

“A lot of people really need to work together to make the most of this one-time opportunity of funding to really move the needle on this issue.”

The recent federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) is poised to provide a huge influx of funding to underserved areas for broadband development. Copeland told The Star that Missouri could get upwards of $1 billion— and Kansas City is already leading the way in promoting digital equity.

“The biggest organized and focused effort in terms of digital equity comes out of Kansas City,” she said. “If there’s an urban area in Missouri that’s well suited to be strategic and supportive for local residents, it would be the Kansas City area.”

Do you have more questions about internet access in Kansas City? Ask the Service Journalism team at kcq@kcstar.com.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies