KC bus agency broke promise to search nationally for CEO, then paid him more than allowed

The Kansas City Area Transportation Authority promised a nationwide search for a new leader to run the regional bus system after the agency’s governing board fired CEO Robbie Makinen last July.

Blaming Makinen for poor bus service and perceived financial mismanagement, city officials had pushed for his ouster and hoped someone with more transit experience would replace Makinen, who had none other than as a board member before becoming chief executive.

But within weeks of announcing the national search for a new CEO, the authority’s board of commissioners abandoned the effort without posting so much as a single help wanted ad, The Star has learned.

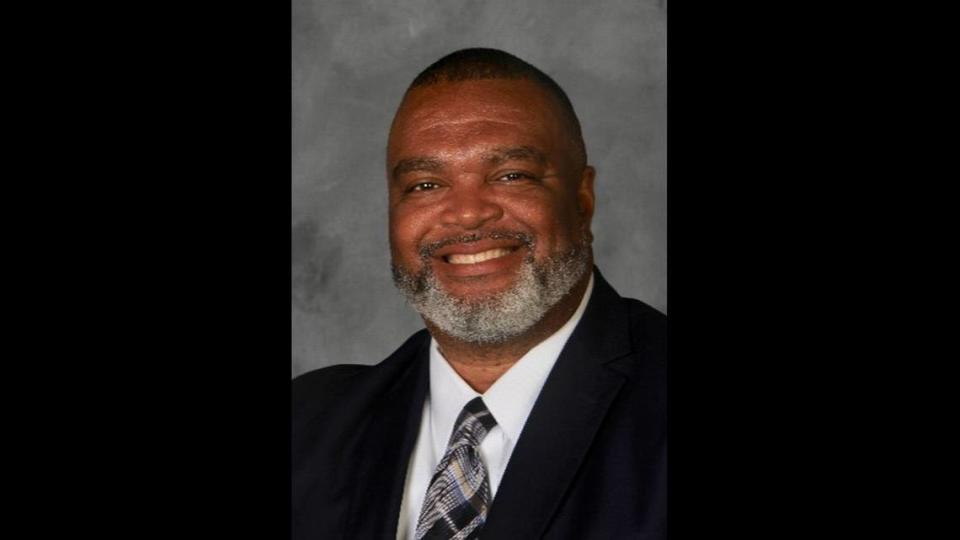

The board quietly decided against hiring any of the three headhunter firms that interviewed for the job. Five months later, it announced that another insider without transit management experience, then interim CEO Frank White III, would get the job permanently.

Like Makinen, White had no experience running a bus system of any size, let alone one as big as the KCATA, which has a $90 million budget and employs 630 drivers, mechanics and administrative staffers.

On Thursday, the board issued a statement defending that decision, saying it was critical to move swiftly at a time when the agency faced a number of challenges to its finances and operations and that White as interim CEO had “demonstrated his passion for our mission” by quickly addressing those issues.

Key among them was the need to hire more drivers and mechanics for a workforce that had been depleted by the pandemic and retirements.

“We named Mr. White our interim CEO because we had serious challenges with service provision, financial accountability and staffing that required immediate attention,” board chairwoman Melissa Bynum said in a written statement. “We had within our ranks a leader who had served KCATA for six years and had the capability to face these issues with the immediacy they required, and the sincere desire to take them on.”

The board gave White a three-year contract in January, a copy of which was obtained by The Star through an open records request. It pays him $275,000 a year, $50,000 more than Makinen received after seven years in the job.

Board members were unaware that White’s pay level was in violation of a city ordinance, a KCATA spokesperson said, until The Star informed them of it in an email this week. The ordinance caps the salaries paid CEOs of agencies that receive more more than 25% of their budgets from city taxpayers, which includes the KCATA.

They can’t be paid more than the city manager, unless the city council grants a waiver. White’s salary is $10,000 more than City Manager Brian Platt is paid annually.

Also, White has yet to comply with another ordinance that requires him to live within the city limits. Although he was aware of the rule when he signed his employment contract in January, he did not begin considering a move from Lee’s Summit or asking for a waiver to the rule until The Star began making inquiries this week, the spokesperson said. He has nine months from the time of his hiring to make the move.

White did not respond to requests for comment.

Councilwoman ‘very disappointed’

When informed of The Star’s findings, City Councilwoman Katheryn Shields said she was disappointed that the KCATA failed to follow through on a national search, describing it as a missed opportunity for possibly bettering the future of mass transit in Kansas City.

“You know, what’s really unfortunate, even beyond these very clear violations of city ordinances, is that the ATA is a very important institution and service provider in our city. And no one responsible on the board bothered to see that they actually were hiring the most qualified, competent person to direct this, you know, multi-million dollar entity,” she said.

“I know that there was a commitment to the mayor and to the city that there be a national search. And I’m very disappointed that the board didn’t do that. And frankly, I’m kind of surprised given that, you know, the city has, I forget how many, representatives on the board but certainly the head of our public works department sits on it.”

City public work director Michael Shaw is one of three KCATA board members appointed by Mayor Quinton Lucas to represent the city’s interests on an agency that gets the bulk of its funding from two city sales taxes. Jackson, Johnson, Leavenworth and Cass counties each have one person on the 10-member board and the Unified Government of Wyandotte County and Kansas City, Kansas, has three.

It was Shaw who told Shields and other members of the council’s finance committee in August that a national search would be conducted for Makinen’s replacement. Shaw asked that the committee recommend that the full council waive the residency requirement for White while he served as interim CEO during that search.

A week later, the KCATA board heard presentations from three executive search firms at its regular monthly meeting on August 24. Prior to that, Bynum and general counsel Patrick Hurley sent a memo to the board that said it was “anticipated that a firm will be selected at the end of the presentations.”

But none was and there is no mention of that decision in the meeting minutes. When The Star asked why no executive headhunting firm was chosen, the KCATA provided this statement attributed to Bynum:

“We did receive presentations from several search firms, however it wasn’t evident that these firms fully comprehended the urgency of our situation. We chose to lengthen the term of our interim CEO and let him continue the efforts he had been demonstrating and save the cost of the search firm. Within months of his hiring, Mr. White demonstrated his passion for our mission, and was in fact producing the outcomes we needed. As a board, we decided to dispense with the search process and secure his employment permanently. We are confident in our decision and have great momentum.”

According to a previous statement from the board, White’s annual contract amount was based on a survey of salaries paid CEOs at comparable sized bus systems as well as White’s “transit experience, education and work accomplishments.”

White’s rise at KCATA

White has a bachelor’s degree of general studies in psychology from the University of Kansas. He had worked in a variety of marketing and sales jobs and was shutting down his small insurance agency when Makinen hired him to fill a newly created position in the KCATA marketing department.

His hiring for a job that had not been advertised raised questions about a conflict of interest because he is the son of Jackson County Executive Frank White Jr., who appoints one member of the KCATA board. Makinen had himself only recently left the Jackson County payroll at the time.

White told the Star then that he thought about refusing the offer for the job paying $80,000 a year because he knew some would think he was getting special treatment due to his famous father, who before going into politics had spent an illustrious career playing for the Kansas City Royals.

“When Robbie first offered it to me, I declined because I didn’t want the hassle,” he said then.

White later moved from the marketing department to KCATA’s real estate subsidiary, RideKC Development. Before becoming interim CEO, he was vice president of business development for RideKC Development and making $148,625 a year..

According to his bio on the KCATA website: “Since coming to the KCATA in March of 2016, Frank has won three First Place AdWheel Awards for marketing and was one of 35 national future transit leaders identified and accepted into the Eno Transit Senior Executive Program, an industry executive training program, recognizing senior executive potential.”

As part of his employment contract as CEO, the board agreed to reimburse White up to $12,000 for hiring an executive coach “to provide him with assistance with setting and achieving his career goals.”

Under the city ordinance, White has nine months from the date of his appointment as CEO to become a Kansas City resident.

The council can waive both that and the salary cap requirements “for circumstances and the city council determines it is in the best interests of the city.“ But neither the KCATA nor White has made either request.

Failure to comply with either ordinance risks a reduction in city funding, according to the twin ordinances adopted in July 2020.

The KCATA said in a written statement that the board may seek a waiver to the residency requirement, although White is willing to move to Kansas City.

The board may also seek a waiver to the salary cap requirement.

‘Same rules’ as city employees

The Kansas City Council adopted both ordinances on the theory that the top leaders of agencies receiving substantial city funding should have to abide by the same rules as city employees of all levels. Lucas was the key sponsor.

“All these people get paid every day to work for the people of Kansas City, Missouri, and we pay their salaries,” Lucas said at the time. “I don’t know why it’s hard for us not to say that ‘yes, that’s an agency that’s accountable to the people of Kansas City and, therefore, should live under the same rules as everyone else does.’”

Since the ordinances passed, the residency requirement for the state-controlled Kansas City Police Department has been relaxed due to an act passed by the state legislature. Police must now live within a 30-mile radius of the city.

But all other city employees and the top executives of certain agencies receiving the 25% level of city funding still must live in Kansas City.

Lucas’s chief of staff, Morgan Said, had this to say with regard to White’s pay in excess of the salary cap and residency status:

“The mayor believes in local control of our tax dollars and stands by his 2020 ordinance. He expects our quasi-governmental agencies to do the same.”

The council waived the residency requirement in 2021 for Kathy Nelson when she was hired to run the city-funded convention and visitors bureau, Visit KC, in addition to her job as head of the privately funded Kansas City Sports Commission.

That waiver was justified, City Councilman Kevin O’Neill said at the time, as Visit KC’s efforts would benefit from having her heading two complementary agencies aimed at drawing tourists and because she had deep local knowledge. Visit KC pays Nelson $240,000 a year, which is below the city’s salary cap.

Makinen also lived outside of Kansas City, but the ordinance only applies to CEOs and other top executive hired after 2020.

Michael Graham, a former chief financial officer of KCATA, said in a recent lawsuit that under Makinen the agency was spending far more money than it took in and that this spending was “unsustainable” and was causing “significant financial problems.”

When Graham confronted Makinen about this, Makinen told him to “take a dull pencil and stab yourself in the eye” and “hide the budgetary imbalances,” his lawsuit says.

Makinen has denied that he mismanaged the agency and claims city officials pressured the KCATA to spend transit funds on city projects like street lights. He recently was a finalist to head the transit agency in New Orleans but someone else got the job.

White has promised to turns things around and build better relationships in the community. His main focus has been on improving bus service, he told the finance committee last August.

“While I am in the position, know that all my time and efforts will be making the service where it needs to be ...,” he said.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies