Kansas City publisher to testify in Kevin Strickland case, says witness recanted to him

The lone eyewitness to the murders that landed Kevin Strickland in prison tried to publicly recant her identification of him twice to The Call, Kansas City’s Black newspaper, its publisher said.

Eric Wesson, who is also managing editor of the weekly paper, said Cynthia Douglas came to the newsroom in 2004 or 2005 to talk to him and Donna Stewart, its publisher then, about her wrongful identification of Strickland in the April 25, 1978, triple homicide.

“She wanted to right or correct that wrong,” Wesson told The Star.

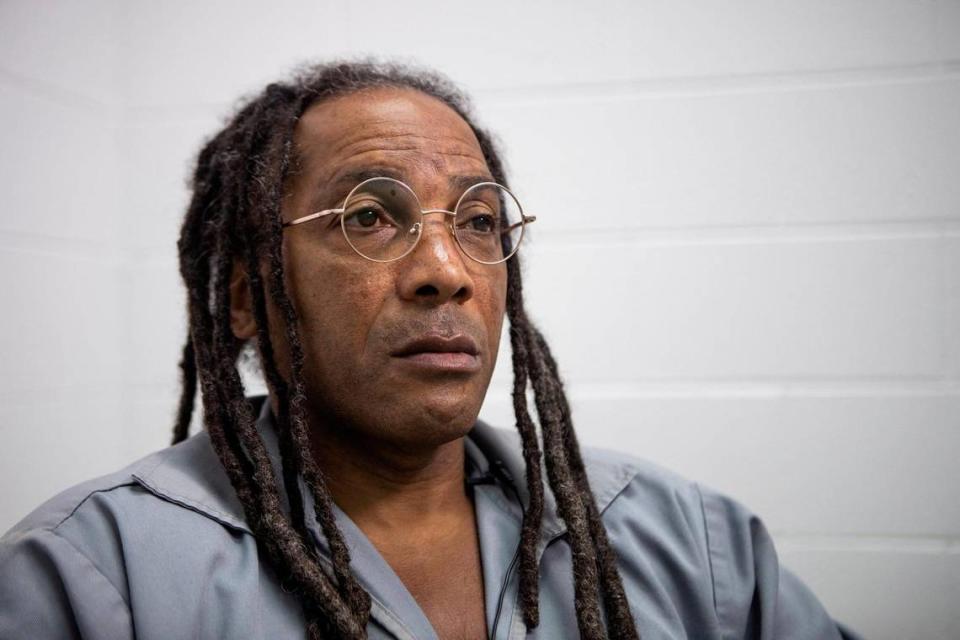

Jackson County prosecutors plan to call Wesson and Douglas’ mother, Senoria, to the stand on Oct. 5 when they argue before a judge that Strickland, 62, has spent more than 40 years in prison for murders he did not commit. Wesson’s testimony is expected to further establish that Douglas tried for years to recant her identification, which was the most incriminating evidence at Strickland’s trial.

Douglas wanted the newspaper, which serves the city’s Black residents, to write a story to “get the truth out” about her assertion that Strickland was not one of the four suspects in the killings at 6934 S. Benton Ave. in Kansas City. By then, Strickland had been in prison for 25 years.

Wesson believed Douglas, especially because he had known her for decades.

The two grew up in the same south Kansas City neighborhood and went to middle school together. He, Douglas and Sherri Black — who was among the victims killed in the shooting — also graduated at the same time from Southwest High School, where they attended classes and ate lunch together.

As the suspects ransacked the South Benton home that night, Douglas, 20, was tied up with Black, 22. The best friends were like sisters; wherever you saw one, Wesson said, you saw the other. Douglas later named her daughter, Sherri Jordan, who is now in her early 40s, after her.

During the shooting, Douglas was covered in Black’s blood and brain matter. She was never the same again, Wesson said. In addition to the trauma of it all, Strickland — who Douglas would testify against but later said “had nothing to do with it” — remained in prison.

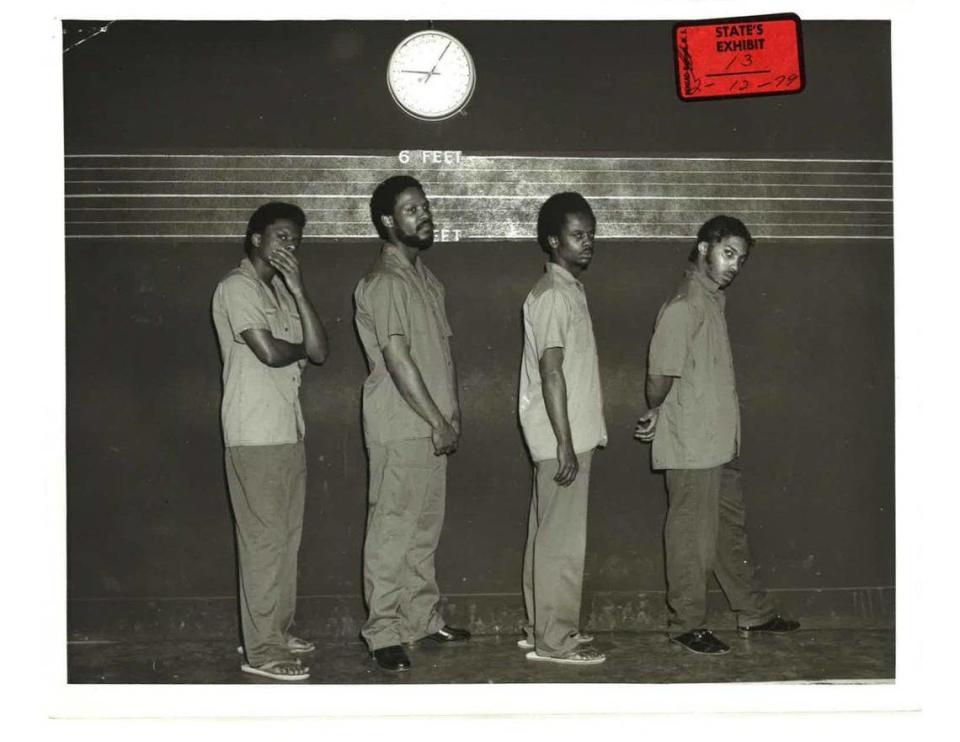

Initially, Douglas told police she could identify two of the suspects, Vincent Bell and Kilm Adkins, but not the other two. The next day, however, she described a shotgun-wielding suspect to her sister’s boyfriend, who suggested the gunman might be Strickland.

She called police and identified him in a lineup.

But four months after Strickland went to prison, another suspect pleaded guilty and insisted Strickland was not involved. Douglas approached a prosecutor to recant, but he told her to go away and threatened to charge her with perjury, according to Douglas’ ex-husband.

Wesson was also devastated by the murders. At the time, he was in Hawaii as a member of the U.S. Marine Corps. He did not know Strickland, who was 18, but he was “real close” to Black.

“Sherri was such a nice person that I could never figure out why anybody would want to do anything to harm her,” Wesson said.

Wesson was a staff reporter when Douglas first approached The Call. He pulled the case file and Strickland’s appeals. Wesson said some of what Douglas remembered was not consistent with the documented evidence, such as who was outside the white bungalow she stumbled out of after she was shot that night.

But one thing Douglas was “always consistent about, whenever I saw her and she brought it up, was that Kevin wasn’t there,” Wesson said Tuesday as he sat in The Call’s office at East 18th Street and Woodland Avenue.

The Call did not end up printing a story. Stewart decided to put it on hold and thought they could do more research, Wesson said.

Wesson does not know why Douglas came by when she did, but the murders and her belief that her testimony sent an innocent man to prison took a toll on her.

Douglas at times dropped by The Call to grab a paper or talk to Wesson about their high school classmates. But it was in 2008 or 2009 that she again tried to get the paper to write about Strickland.

She was frustrated that “nobody would listen to what she was saying,” including police she said she spoke with, Wesson recalled. She also tried reaching the prosecutor’s office, he said.

“I don’t know what to do,” Douglas told him.

Wesson suggested she write to a federal appeals court judge.

‘The only eyewitness’

At the time, Douglas was working in accounting at the Jackson County Family Court Division.

In 2009, an email from her work account was sent to the Midwest Innocence Project with the subject line, “Wrongfully charged.” It said she was seeking information about “how to help someone that was wrongfully accused.”

“I was the only eyewitness and things were not clear back then, but now I know more and would like to help this person if I can,” read the email sent at 12:40 p.m. on a Wednesday.

Six years later, Douglas died at age 57.

Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker’s office has determined that Douglas’ email was an “unequivocal recantation.” Prosecutors claim witness tampering was highly unlikely, given the email’s circumstances.

The Missouri Attorney General’s Office, which contends Strickland is guilty and is fighting Baker’s effort to exonerate him, has argued the email is “remarkably unreliable” and noted it does not name Strickland. A judge can’t know if Douglas sent the email, “let alone absent coercive pressure,” the office said.

But Wesson said Douglas told him that she planned to send the email from her work account — which ended with “@courts.mo.gov” — so someone would pay attention to it. She joked she might get fired over it.

“She said, ‘I’ll probably lose my job using Jackson County’s email address, but maybe people will take me serious if I’m using that email address,’” Wesson told The Star.

Baker said she is grateful witnesses, such as Wesson, are willing to come forward to testify in court about what they know.

“We really look forward to presenting him before a judge,” she said.

It’s not clear if Douglas approached other news organizations. The Star more recently became aware of Strickland in December 2017, when he wrote to the paper asking for an old article about the shooting. Under his signature, he penned: “Wrongly convicted.”

In an investigation published in September 2020, The Star reported that Douglas, whose testimony was paramount in the case against Strickland, told her mother, her ex-husband and her siblings that she wrongly identified Strickland for another teenager.

She tried to set the record straight repeatedly, they said. She wanted Strickland freed.

“You put that in your report,” Senoria Douglas, then 83, told a reporter in 2019, speaking slowly but confidently, an emphasis between each word. “Let. Him. Go. Set that man free.”

The Star also reported that, for decades, two men who pleaded guilty in the killings swore Strickland was not with them and two other accomplices. A third, uncharged suspect has also since called Strickland innocent.

Wesson said he is glad Strickland’s case has gained attention. He has written about it several times now at The Call.

For the Fourth of July edition, The Call’s entire front page featured a photograph of Strickland with the headline, “Free Kevin Strickland,” followed by a smaller subhead that read: “When Is His Independence Day Coming?”

In a story on the second page, Wesson mentioned that Douglas spoke about the case to him years earlier. She explained, he wrote, that “she didn’t really see the other shooter but was led to believe that it was Strickland.”

The attorney general’s office will depose Wesson and Douglas’ mother on Friday, ahead of the Oct. 5 and 6 evidentiary hearing. Strickland could be exonerated after that if Baker’s office prevails.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies