Kansas City couple’s biggest house flip yet: mansion that was Rockhill Tennis Club

President Teddy Roosevelt once stood in this room, in 1917, with its scrolled plaster walls and pink marble fireplace from France.

Little might he have imagined that a family of raccoons would many years later take up residence in the Kansas City mansion that had fallen into disrepair, their paw prints still visible.

So, too, for generals John “Black Jack” Pershing and Ferdinand Foch who, in 1921, unpacked their uniforms, ribbons and medals inside the mansion called “Stonehouse” at 4520 Kenwood Ave.

The three-story, 10-fireplace home was built in 1910 as a wedding gift for Irwin and Laura Nelson Kirkwood. She was the daughter of the powerful founder of The Kansas City Star, William Rockhill Nelson, whose own sprawling mansion, Oak Hall, stood across the street where The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art now exists.

In a historic union, the commanders of the American and French forces in World War I would leave the house that November day in 1921 to stand alongside their allies from Britain, Belgium and Italy and, before a throng of 100,000 cheering people, dedicate the site of the future Liberty Memorial.

Now, 100 years later, the newest owners of the home, Peter and Heather Caster, are attempting to create some history of their own.

They are house flippers — former hair stylists who fell in love at the Antioch Shopping Center. He, an avid runner from Gladstone. She, a body building champion and “country girl” from Trimble, Missouri. This is their biggest flip yet:

The renovation of what may be destined to become one of Kansas City’s most noticeable homes when, as early as June, or perhaps the fall, the Casters say they may put it back on the market for $2.5 million. Their website, 4520kenwood.com, is already seeking interested buyers.

“Like imagine that movie, ‘The Money Pit,’ where they come out with the coffee and the robe,” surrounded by construction, Heather, 35, said on a recent visit. “That’s been our life.”

“Except we’re not ending in divorce,” said Peter, 43.

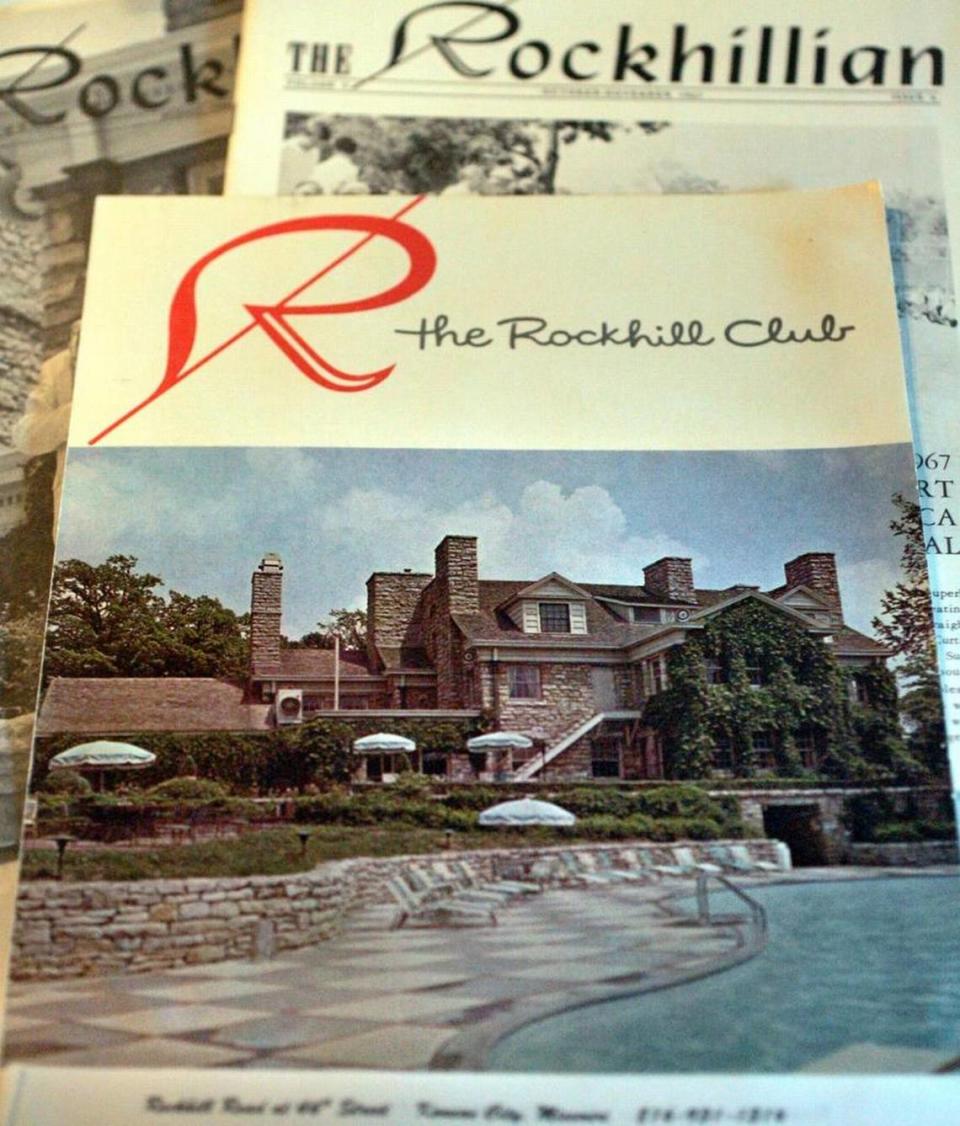

Their project for the last two years has been to take what was once the Kirkwood mansion, later the home of lumber business and social leaders DeVere and Pauline Dierks and then, for some 53 years, the 17,000-square-foot clubhouse for The Rockhill Tennis Club — jammed with lockers, bad plumbing, old showers, mold, an industrial kitchen thick with grease — and turn it back into a single-family house for sale.

“Basically,” Peter said, “this is like 50 flips in one.”

In February 2019, the Casters bought the home on three-quarters of an acre from the Nelson museum for $485,000. (The museum had been willed the house on four acres by the Dierkses in 1957 and, until 2010, had been leasing it to the tennis club.) Peter estimated that the couple have already pumped $750,000 into renovations and are likely to hit $1 million.

Even at that, he said, theirs is not a full, top-to-bottom every-square-inch renovation. The house needs so much work that any new owner is likely to want to do more. But the Casters think that a major selling point is its future, although it’s one that remains uncertain.

The Nelson still owns some three acres surrounding the house on three sides. For at least 13 years, the museum has talked about expanding its sculpture park to the east across Rockhill Road.

Even if the next owner pumps another $1 million into it, Peter calculates, they’ll be getting a historic mansion on a hill that one day will overlook millions of dollars of art in a gorgeous sculpture garden: money well spent.

“You’re going to have a property unlike anyone else’s,” Heather said.

One big family

“Do you want to tour the house?” Heather asked, standing and heading to the front door.

She and Peter had been sitting in the French parlor, on a settee sofa that Heather had recently dyed a shade of red.

The couple are energetic, fit, affable, with clean-cut looks — Peter’s older Ken to Heather’s younger Barbie. Married in 2006, they met when Heather, raised by a construction worker dad, was just about to turn 19 and was, as she called herself, “punk rock kind of wild” with spiky black hair and piercings.

Peter, at 26, had already been married and recently divorced from his Winnetonka High School sweetheart, class of ‘96. He ran cross country at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, which is when he fell in love with the homes around the Country Club Plaza, Hyde Park, Southmoreland and the Rockhill neighborhoods. With the first two of his children soon on the way — Madelynn, now 21, and Mason, now 20 — he left UMKC to attend beauty school and work with his dad, Paul Caster, who owned Hair Cutters salon in Antioch mall.

By 22, he had already gotten into real estate, buying and renovating small houses for extra money. Then Heather, a recent beauty school graduate, walked into the salon for a job interview.

“Basically we started dating right away,” Heather said. “We dated for two years and he asked me to marry him.”

In 2010, they would have their daughter, Piper, now 11, and who by 18 months was diagnosed with a rare neurological disorder, Rett syndrome, that has left her unable to walk or talk or eat on her own. Their relationship with her, they say, has only inspired their lives and deepened an already ardent Christian faith.

“For a lot of people that would tear them apart,” Peter said.

“That’s the thing that really glued us together,” said Heather who, once Piper was diagnosed, dedicated herself for a number of years to competitive natural body building because she felt her daughter needed a healthy and strong mother.

And it’s given them perspective on the house and their often changing decision on whether to sell or make it their family home. Currently, six other family members live there with them: daughter Madelynn and her husband, Tyler; son Mason and his fiance, Sierra, soon to be married at the house; Peter’s father Paul and his partner, Deb.

“Like, we love it,” Heather said of the mansion. “Like we put our blood, sweat and tears into this house.”

“But when it comes down to it,” Peter said, “ it’s just a possession. It’s not important enough to be above just a possession.”

Almost didn’t get the house

The tour started at the front door to the east — heavy wood, and thick. The top half is glass, etched with a large “R” for the Rockhill Tennis Club. It opens into a small, square foyer of natural limestone. Light peeks through a leaded glass window with a grid of 25 panes.

“Those windows,” Peter said, admiring the light, “are not being replaced.”

From there, one enters an expansive and sumptuous mahogany-colored wood hallway, 825 square feet extending nearly the entire east-west center of the house. It has floor-to-ceiling wainscoting with deep inset panels, a beamed coffered ceiling with a grand staircase to the north.

“All this stuff you see,” Heather says, “like all this woodworking. . .”

“Mill work,” Peter interjects.

“Was just like it is,” Heather says.

“Didn’t touch it,” Peter says.

Except for cleaning: Mold, although luckily not black mold, had grown in multiple corners of the house.

“When we took possession of the house: ice cold,” Peter said. “The boiler doesn’t work. They didn’t winterize the property. It burst all the pipes. Back bathrooms were covered in mold.”

Ceilings were hanging like rags from age and water damage. Most have since been repaired and painted. White oak hardwood floors, in a herringbone pattern, are refinished.

In many ways, the Casters are surprised to even have the house. Both have worked full-time in real estate for years. Peter has been an agent for 19. He estimated they have flipped at least 60 houses in the last decade alone. As agents, they’ve sold many more.

When the Rockhill mansion came up for sale, hearing it might need as much as $2 million to renovate, they wanted it so much they offered $70,000 over the asking price of $289,000.

“Come to find out we didn’t get it,” Peter said. He remembers being told that someone had “substantially” outbid them.

“I don’t think I slept for two days,” Peter said. “I just kept pacing around going, ‘This is unbelievable.’”

So they made a backup offer: $500,000. But still, Peter said, they heard nothing, until . . .one year later. They were on a cruise in the Caribbean when the museum called. The other deal had fallen through. Were they still interested?

The Casters estimated they have since employed at least 50 subcontractors: electricians, carpenters, masons, window installers, concrete workers, roofers, landscapers, plumbers. The house has nine furnaces. New kitchen. New bathrooms. New driveway. Power lines are to be buried. A new garage is planned.

Upstairs, downstairs

From the hallway, the Casters move to the south into the French parlor room. “We’ll go around in a circle,” Heather suggested.

Scrolled plaster that had cracked and fallen from the walls has been fixed and painted a cream white.

In the library to the north, which the Casters are making a dining room, Heather pointed to what looked like smudges near the baseboards, soon to be painted.

“You can still see where the raccoons lived,” she said. “See those paw prints? Those were all throughout the house when we came in here. We had a whole family of raccoons living in the attic.”

The attic crawl spaces are on the third floor, which according to historic stories in the The Star were servants quarters. In April 1925, the Dierkses, who owned the home by then, had placed a telling ad regarding race.

“Help wanted: Female cook; experienced; white, city reference. Mrs. Dierks, 4520 Kenwood Avenue. Phone Hyde Park 3428.”

In March 1932, another story noted that a flue fire caused $5,000 of damage to the quarters. It was an amount that, at that time, was at least four times the annual salary of the average Kansas City homeowner.

The Casters have now turned the quarters into three bedrooms, two bathrooms, a modern kitchen and living room, effectively a third floor residence of its own.

“All four of the kids — we just call them kids, ” Heather said of the adult children and their partners. “All four are on the third floor.”

Back downstairs, the Casters show what used to be the tennis club’s 1,200-square-foot dining room, with existing two-sided gas fireplace, and, beyond that to the north, another open room, an additional 1,400 square feet, with a wood bar and stools that the tennis club added to the mansion. The Casters figure it would be for parties. They opened up the north wall with sliding doors to the outside. They’ve left the long, horizontal bar, but added appliances and another new bathroom in deep blue tile, a tiny sewing and nap room.

The biggest change to the first floor is the kitchen. The old one’s gutted.

“This place was black, scary,” Heather said.

Everything’s new — pantries, cabinets, 60-inch six-burner chef’s gas oven, two refrigerators, a new door that never existed and windows to the east that opens to walking stones and new landscaping. A bathroom has been added with a walk-in shower of white tile.

In the 6,000-square-foot basement — a winding labyrinth of stone walls and narrow passageways that once housed the club’s locker rooms and showers — the couple have painted the stones, redone the floor and added new lighting. The sauna is up and running. A hot tub still needs repair. The place is filled with bar bells, workout machines. They have kept a row of lockers.

“Our mindset was to do the basement as cheap as possible,” Peter said. “Our thought on that was what could we do to make it usable. So we went and bought out a gym that went out of business so, basically, we have a 6,000-square-foot gym.”

Upstairs, the club’s former second floor pub on the west side of the house is now a master bedroom. Behind an old bar, the Casters broke through a wall to reveal a hidden fireplace at the center of a limestone wall. The wall with the mantel are now the focal point of a new bathroom with a claw foot tub beneath a large window.

“This is where she takes a bath looking out over the Nelson,” Peter said.

“Do you want to see the tiny house?” Heather soon offered and headed outside.

Neighbors, a tiny home and ... a ghost?

Homeowners in the Rockhill neighborhood are said to be happy, overall, with what the Casters are doing, although they are also watchful. Club members and neighbors fought the Nelson in 2008 after the museum made it clear it would no longer lease the property to the tennis club and, initially, proposed turning the house into offices for museum staff.

If the club could not be kept going, they at least wanted the house reverted to a single-family home. That’s what’s happened.

“It’s working out. It provides the Nelson with plenty of space for outdoor sculpture for the long-term,” said Marshall Miller, an attorney, spokesman for the Rockhill Homes Association and resident who joined the tennis club in 1975. “It’s a very pleasant look and everyone is getting along.”

Patricia Miller was married at the club in 1961. Her children spent summers at its pool, torn up years ago. Her late husband used to tell a story of how he once broke into the home when he was a boy.

“I have a picture of myself coming down that staircase when I’m throwing my bouquet,” said Miller, who kindly declined to offer up her age. When the Rockhill Tennis Club closed, she purchased the club’s painting of Laura Nelson Kirkwood that now hangs in her home. Kirkwood sits in a yellow gown on a bench, her father’s mansion behind her.

“I suppose you know about that ghost, don’t you?” Miller said. For years, the story has been told that after Laura Kirkwood died in 1926, alone in a Baltimore hotel at age 43, that her spirit came to occupy the house on Kenwood Avenue.

“She had quite a bit of sorrow in her life,” Miller said. “The legend is that she was just there. A lot of people have had experiences with her. Like you’d be in a room and the door would just close and you couldn’t get out. Or they would feel a draft. I did feel her about two or three times.”

Miller also feels positive about the home finally being redone.

“Oh, we’re delighted it’s a single-family home,” she said. “It was beautiful, just a beautiful house.”

Change, nonetheless, can also raise concerns.

Outside, on the north side of the home, Peter and Heather show off a new single bedroom guest house they have created, taking what was once the club’s existing snack stand and the tennis pro shop and linking them together under a single roof with limestone wall. It has a full kitchen, a bathroom, washer and dryer and a small wood deck facing the Nelson museum.

It’s 600 square feet.

“It’s somewhere between a tiny home and a one-bedroom apartment,” Peter said.

Nearby, also facing the Nelson, a wood pergola was rising above an 18 foot by 24 foot patio. There was a fountain and outdoor lighting.

“Historic Preservation never OK’d the pergola,” Peter said. He also needed to get the lighting and fountain checked. “I should have called Historic Preservation before starting. I didn’t think it would be a problem. We went right on top of where an old pergola was for the tennis club.”

A hearing is set for May 28. If the work doesn’t meet guidelines or code restriction, it would need to be removed.

Meantime, the Casters intend to keep working with the intent to sell, whenever that might be.

“Sometimes these large homes take forever to sell,” Peter said.

“We could still have it on the market and still be living here,” Heather said.

“I would just do more and more,” Peter said.

“Right,” Heather said. “we’ll just make it better.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies