Joy, grief collide at indie rock band Japanese Breakfast’s show at the Cat’s Cradle

After the indie rock band Japanese Breakfast took the stage at the Cat’s Cradle, frontwoman Michelle Zauner greeted the crowd with a shy smile.

The band opened their set with “Paprika,” the first song off their most recent album, “Jubilee.” Zauner’s voice carried the melody before triumphant drums and trumpet joined in. Finally, Zauner picked up a mallet to bang a gong and began the chorus:

“How’s it feel to stand at the height of your powers / to captivate every heart?” she sang, describing the very experience she was having onstage — performing live music for a crowd shouting lyrics in unison, sticky with sweat, transcendent with the collective rush that the pandemic has made impossible for so long.

“Projecting your visions to strangers who feel it / Who listen, who linger on every word?”

The song’s refrain — “Oh, it’s a rush” — seemed equally as true of the audience’s experience as Zauner’s.

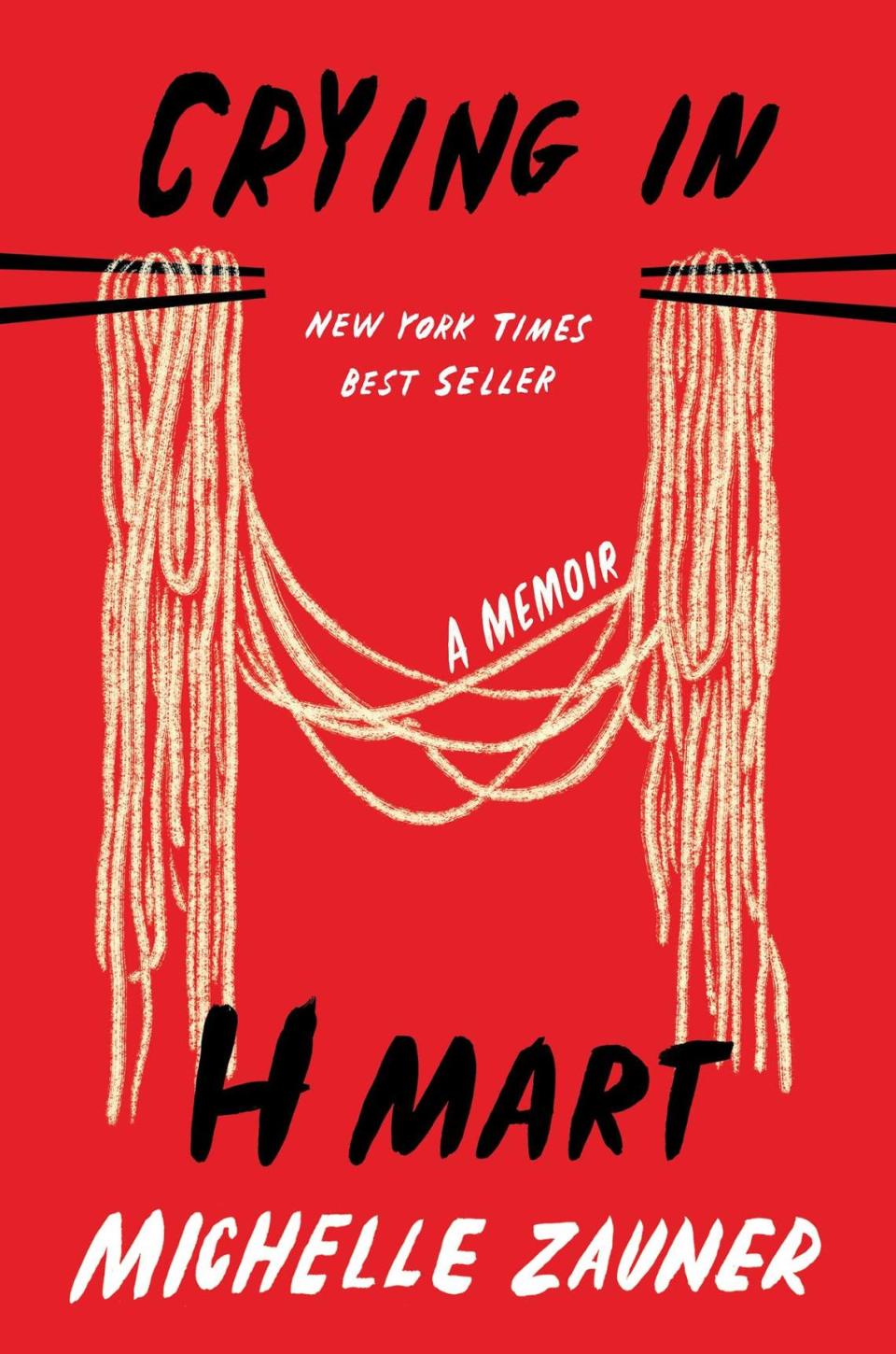

“Jubilee” is Japanese Breakfast’s third studio album, following “Psychopomp” (2016) and “Soft Sounds from Another Planet” (2017). Zauner — who was born in Seoul, South Korea, and moved to the United States before her first birthday — has also become widely known for her memoir “Crying in H Mart,” about how Korean food shaped her relationship with her mother and helped her cope with her death.

Before Monday night’s performance at the Cat’s Cradle started, I spoke with some people in the audience about what brought them to the concert. Some were longtime fans, and many said they were introduced to Japanese Breakfast through “Jubilee” and Zauner’s memoir.

Ian and Sydney Maynor — two siblings from Pinehurst, about an hour from Carrboro — told me that they were half-Korean like Zauner, and that they came, in part, because of how much they related to her memoir.

“It’s cool to see a half-Korean woman perform here,” Sydney said. “There are, like, no Asian people where we’re from.”

Japanese Breakfast is one of, if not the only, Asian American artists who will perform at the Cat’s Cradle over the next few months. In the music world — especially the rock music world — Asian Americans are still few and far between.

Zauner has spoken and written about feeling like an outsider in the indie rock music scene because of her race. But both her band and her book have skyrocketed to success. Thirty-two of her 58 remaining U.S. shows sold out, including the Cat’s Cradle one, and “Crying in H Mart” has been a New York Times bestseller since its release in April.

Ian Maynor said seeing a high-profile artist like Zauner identify so closely with her Korean heritage, especially in “Crying in H Mart,” made him feel more comfortable in his own identity.

“Like I don’t have to prove anything,” he said.

“Reading her memoir and seeing her perform — it shows you there are different ways to be Asian American,” adds his sister, Sydney. “It makes you feel less alone.”

Moving forward

The first time I read “Crying in H Mart,” I was on a train from Seoul to Busan in South Korea with my mom on our way to visit family. The train was sleek and gray and quiet, and we were both falling in and out of sleep.

It was August of 2018, and I was scrolling through Twitter on the train when I saw that The New Yorker had just published an essay by Zauner that would later become the first chapter of her memoir.

“Ever since my mom died,” Zauner begins the essay, “I cry in H Mart.” H Mart is a Korean grocery chain specializing in Asian food that originated in Queens and has spread to cities from London to Cary.

She goes on to explain that losing her mom meant not only losing one of the most important people in her life, but also her connection to her Korean heritage. She wonders, “Am I even Korean anymore when there’s no one left in my life to call and ask which brand of seaweed we used to buy?”

When my grandmother died, my mom and I experienced something similar. As more time passed, we felt further and further from the people we were when we were with her, and further from the culture she shared with us.

But as I read “Crying in H Mart,” my understanding started to change of what it means to be Korean. After Zauner’s mother’s death, she had to forge new ways of connecting with her heritage.

Food — slurping thick, salty black bean noodles in the H Mart food court, or making kimchi alone on the floor of her Brooklyn apartment — became her way of “collecting the evidence that the Korean half of my identity didn’t die when [my mom and aunt] did.”

These are the memoir’s little shimmering moments of joy, shining softly but steadily out from the grief. And they showed me being Korean wasn’t necessarily just reaching backwards, for something that once was. Maybe it could be moving forward, too.

An album about joy

When Zauner announced the release of “Jubilee” on Twitter, she said it was an album about “joy.”

Like “Crying in H Mart,” much of Japanese Breakfast’s earlier two albums grapple with Zauner’s mother’s death from cancer in 2014.

So for Zauner, “Jubilee” was a purposeful pivot away from the grief that has been intertwined with much of her previous art. She said in an interview with The Reader that “writing [Crying in H Mart] felt like a real closing of that chapter for me,” while “Jubilee feels like this sort of beginning of a chapter where I can write about other things.”

Nowhere, perhaps, was that joy more evident than during the second song of Monday night’s set, “Be Sweet,” the disco-inflected and infectiously catchy lead single off “Jubilee.” As Zauner performed in a glittery yellow slip dress — dancing, smiling, using her arms to emphasize lyrics — she and the audience seemed to hand energy back and forth to each other.

Zauner let the audience take over the chorus for a moment: “Be sweet to me, baby / I wanna believe in you / I wanna believe in something.”

But the set, of course, also included songs from the band’s first and second albums. After the cheery “Be Sweet” died down, speakers played the piano flutter that begins “In Heaven,” a song from Japanese Breakfast’s first album about the aftermath of Zauner’s mother’s death.

“The dog’s confused / She just paces around all day / She’s sniffing at your empty room,” Zauner sang, eyes closed at the microphone, as she described details that she also writes about in “Crying in H Mart.”

She continued with lyrics that felt like a permutation of the happier “Be Sweet”: “I’m trying to believe / When I sleep it’s really you. … Oh do you believe in heaven? / Like you believed in me.”

Joy, it seems, is not so easily siphoned off from grief.

Drawn to dance

Around halfway through the show, what felt like its climax arrived — “Posing in Bondage,” a slow, sultry ballad from “Jubilee,” about someone waiting and longing for their lover’s affection.

For the song, the lighting shifted, so that Zauner was backlit and only her silhouette was visible.

“Posing in Bondage,” like many other songs from “Jubilee,” feels more like a short story or vignette than a narrative with a direct connection to Zauner’s life. This seems like it was part of the album’s direction away from grief. These songs are full of longing, but not the deep grief that characterizes songs like “In Heaven.”

But shadows of Zauner’s experiences with grief still linger in the lyrics, themes and sounds of “Jubilee.” Zauner sang in “Posing in Bondage”: “When the world divides into two people / Those who have felt pain and those who have yet to.”

She was directly echoing a line from “Crying in H Mart,” when Zauner’s aunt comes to visit after her mother’s death. “It felt like the world had divided into two different types of people, those who had felt pain and those who had yet to,” Zauner writes. “My aunt was one of us.”

Rather than detracting from the mission of “Jubilee” — to mark a transition toward joy — this inability to neatly divide between heavy and light, joy and grief, added richness to the album and the performance.

After Japanese Breakfast exited for their encore, Zauner returned to the stage with her guitar for “Diving Woman,” the six-and-a-half minute long guitar-heavy opener of Japanese Breakfast’s second album.

Over the guitar riff that runs throughout the song, Zauner sang, “I want to be a woman of regimen / A bride in her home state / A diving woman of Jeju-do.”

The song references the haenyeo, or diving women, of Jeju-do, an island off the southern coast of South Korea, where my grandmother was born. Haenyeo dive into the grey seas off Jeju-do with no breathing equipment to harvest seaweed, mollusks and other seafood. They’re known for being tough, no-nonsense, representative of the semi-matriarchal society of Jeju.

In “Diving Woman,” Zauner longs for many things. She imagines domesticity, the role of bride and daughter, as a possible source of stability, but she also understands the contradictions inherent in that longing — she wants to give and to receive, dependence and independence, all at once.

“I want it all,” she sang. “I want it.”

During the long interlude where Zauner and her bandmates play electric guitar over the riff that underlies the song, Zauner alternately bent over her guitar in concentration and bounced around the stage.

As I watched, I felt the joy of being in a crowd of people, finally able to be together for a live show, while knowing that there is still so much uncertainty, so much left to grieve. I felt Zauner’s knotty relationship to the figure of the haenyeo — her identification with it, but also her desire to make it her own.

I felt all the contradictions, the joy and grief at once, spill over the bounds of my body. And I felt myself, too, drawn to dance.

I looked around me and saw hundreds of bodies, illuminated by the colorful lights from the stage, doing the same thing. I was not alone.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies