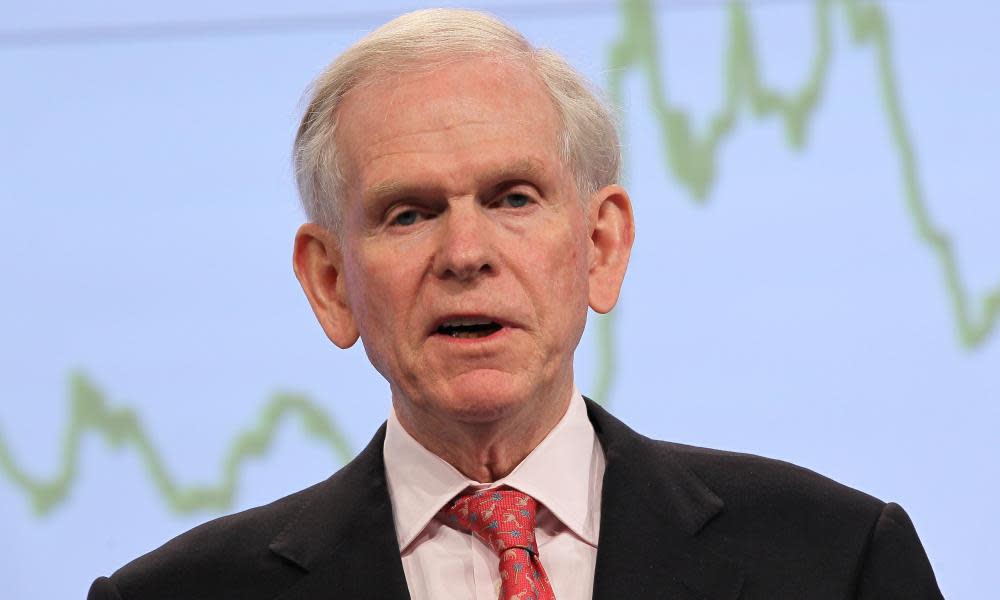

If Jeremy Grantham is talking about a US ‘superbubble’, we should listen

The Boston-based fund manager has hard-to-deny evidence to back up his prediction of a ‘wild rumpus’

Jeremy Grantham’s warning that share prices are heading for a mighty fall is just part of the new year financial calendar, say his critics. On this occasion, however, the British co-founder of Boston-based fund manager GMO and highly regarded observer of stock market bubbles, may have got his timing spot-on.

Certainly “Let the Wild Rumpus Begin” was a terrific title for Grantham’s piece last week: a rumpus is roughly what we’re seeing, at least if one looks at the US, where the technology-heavy Nasdaq has lost 16% since the start of January. It was clobbered so severely on Monday that even the UK’s FTSE 100 index, a decidedly non-tech collection of stocks, was obliged to react to the apparent shift in investor sentiment. The Footsie lost 187 points, or 2.6%, even if a possible Russian invasion of Ukraine was also in the mix.

Grantham’s thesis is that US stocks are in a “superbubble”, an upgrade on last year’s diagnosis of “an epic bubble”, and that the US has seen only three other such extreme events in the past 100 years – the Wall Street crash of 1929, the turn-of-the-millennium dotcom mania and the housing market madness of 2006.

He ran through his checklist of a late-stage bubble, of which “the most important and hardest to define” is “the touchy-feely characteristic of crazy investor behaviour”. On that score, he has hard-to-dispute examples: the meme stock merriness of a year ago; dogecoin, a parody cryptocurrency, rising to a value of $90bn “because Elon Musk kept joking about it”; and shares in car hire firm Hertz soaring because the company said it would order some Teslas.

Those episodes are now over, reckons Grantham, and we’re on to “the vampire phase” of the bull market. Share prices have defied Covid, the end of quantitative easing and the promise of higher rates but, “just as you’re beginning the think the thing is completely immortal, it finally, and perhaps a little anticlimactically, keels over and dies”.

It’s strong stuff and there are, of course, counter-arguments. Corporate earnings are not, on the whole, collapsing. The easing of the Omicron variant may shift western consumers away from consumption of goods and towards spending on services, which could take the edge off current inflation worries. The end of the era of ultra-loose monetary conditions could still be gradual. On the other hand, one should also remember Grantham’s warning a year ago that great bull markets can turn down when the conditions are still favourable – they just have to be “subtly less favourable than they were yesterday”.

Therein lies the debate over whether we’re seeing the removal of some puffed-up extreme over-valuations in corners of the US tech market – think Netflix and Peloton last week – or the start of wider declines for stock markets, fuelled by inflationary problems in energy and food. Grantham’s argument, note, isn’t just that US shares are over-priced; he also includes US houses (“at the highest multiple of family income ever”) and bonds too. It’s the simultaneous nature that, in his view, makes the bubbles so dangerous.

He isn’t always right, but he is a serious student of markets who called the dotcom and 2006-08 crashes with impressive precision. He’s worth listening to. Ukraine aside, the debate he is describing is exactly the one obsessing investors currently. The test of his thesis has been a long time coming.

The stakes are high for Unilever

Unilever, up 7%, defied the gloom as it continued to be a one-company news machine. The latest development is Nelson Peltz, fearsome US activist investor at Trian Partners, taking a stake, reported the FT.

The consumer goods industry is territory Peltz knows well from campaigns at Procter & Gamble and Mondelez. The hard part is guessing what he might want – there’s bound to be something. Possibilities range from a break-up, meaning the sale of Unilever’s food division, to a simple request that the company run its current operations better. Whatever it is, “the fox would now appear to be inside the henhouse”, as Jefferies analyst Martin Deboo put it.

An open question, though, is whether the fox will want a seat on the board. Peltz secured that position at P&G. To put it mildly, it would not be Unilever’s usual style to offer a directorship to an aggressive outsider. Allowing the activist to force a vote on the matter would be risky, however. In their current mood, shareholders may give the wrong answer.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies