Injured cruise ship worker ‘forgotten’ after seven months in South Florida hotels

From behind the locked window of his 10th-floor hotel room, Paúl Córdova watches dozens of airplanes take off and land each day at Miami International Airport.

He can’t get on any of them.

An injured Royal Caribbean Group crew member, Córdova, 48, has been living in South Florida hotels since January. He traveled from Peru to the U.S. to receive follow-up treatment for back surgery he had in November 2018. Back then, doctors replaced two herniated disks in his spine with titanium plates, repairing damage from years of lifting and lugging 50-pound chlorine containers aboard Celebrity Cruises ships.

For 95 days, he has repeatedly asked the Miami-based company to send him home to Peru, where his wife and two teenage children are waiting for him. Though five repatriation flights for crew members have left since April, the company either did not respond to his pleas or said his repatriation was impossible at the time. After receiving questions from the Miami Herald on Friday about Córdova’s situation, the company indicated it is going to send him home on Sept. 1.

“We have been working with Mr. Córdova to get him home in a challenging international travel environment and currently understand the next opportunity to do so is on Sept. 1,” said company spokesperson Jonathon Fishman in an email. “We all share the same goal of getting him home as quickly and safely as possible.”

Córdova has become yet another casualty of the cruise industry’s chaotic journey through the COVID-19 pandemic. His name could be added to a list of more than 100,000 cruise ship workers who have spent months stranded away from their families.

Investigation

How many coronavirus cases have been linked to cruises? Check out the latest numbers

The Miami Herald investigated COVID-19 outbreaks on cruise ships. Explore the findings of the most comprehensive tracking system of coronavirus cases linked to the cruise industry.

After the industry shut down in mid-March, cruise companies repatriated all passengers by early June. But the process for repatriating crew has been much slower due to limited, expensive travel options and virus-related restrictions in the U.S. and in their home countries. Thousands of crew members are still stuck at sea without pay, waiting to be sent home. At least 29 have died from COVID-19, and at least two have leaped overboard in apparent suicides.

More than a dozen crew members, including Córdova, are still stuck in Miami lodgings, unable to get home.

U.S. labor protections do not apply to cruise ship workers because cruise companies are registered and flag their ships abroad. Royal Caribbean Group is incorporated in Liberia and flags its ships in Malta and the Bahamas. Under the Maritime Labor Convention of 2006, the only international protections in place for seafarers, companies are required to repatriate crew. The U.S. is not one of the 97 countries that has ratified the MLC and does not enforce its worker protections.

On a normal pre-pandemic day, the Seafarer’s House at Port Everglades is a refuge for dozens of crew members taking a break, a place to access free WiFi, send money and packages home, buy toiletries, and receive spiritual support.

Since the industry shut down in mid-March and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention banned shore leave for crew still on board, director Lesley Warrick and her team pivoted to caring for more than 60 crew members recovering from various ailments in South Florida hotel rooms for several weeks — and sometimes several months — during the pandemic. Her team is still caring for around eight seafarers.

”They are anxious and the overwhelming message we get is we just want to go home,” Warrick said.

In early April, Warrick connected with the Philippines embassy after a Filipino crew member with COVID-19 was released from a South Florida hospital with only a hospital gown. She provided him with clothes and toiletries until his luggage arrived several days later after being disinfected.

She suspected there were more people in this situation and asked cruise companies for a roster of crew members staying at the hotels. Córdova wasn’t on any of the lists. Neither were another half dozen in his current hotel.

Missed opportunities

As a mechanical welder in the coastal city of Trujillo, Peru, Córdova didn’t think there was work for him in the cruise industry until his wife’s aunt introduced him to a mechanic who worked on Royal Caribbean ships in 2007. Within a few months he got his passport and was on his way to the Celebrity Galaxy ship for a nine-month contract as a handyman making $1,600 per month — about 50% more than what he was making in Trujillo. His son was three years old, and his daughter hadn’t yet turned one.

For the next five years his contracts kept him away from his family on Christmas and New Year’s. His supervisors promoted him from handyman to plumber, and he became a sanitation engineer in 2010, the person on board in charge of managing the pool, jacuzzi and drinking water. He was proud of his work and grateful to be able to send home money to help pay for his family’s rent and food. He wished he could have clocked his real hours, which sometimes reached 15 per day, instead of the maximum 13 allowed.

In July 2017 he visited the ship’s medical center for back pain, which had started a few months before and worsened so much that it was difficult to sleep. A doctor prescribed him ibuprofen and told him to come back in a month if it still hurt. It did. He kept working until he could leave the ship at the end of his contract the following month.

At home in Trujillo, the pain got worse, according to medical records. An MRI showed Córdova had herniated discs; doctors recommended surgery.

“I left with so much hope to return to work,” he said. “It was my way to live and to sustain my family. I never imagined I would need surgery, I thought it would be a treatment of a few weeks, maybe months.”

International maritime law requires that cruise companies provide medical care, housing and food for injured workers until they return to maximum health.

But the surgery kept getting delayed. Desperate, Córdova contacted Miami lawyer Tonya Meister and asked her to help him urge the company to get him the surgery.

Royal Caribbean flew Córdova to South Florida in May 2018 to see doctors in Miami, who recommended injections. They didn’t help. Finally, in November 2018, he got the back surgery in Miami.

He returned to South Florida several times for follow-up visits, most recently in January, where he was placed at the Plaza Hotel in Fort Lauderdale with about 15 other injured workers. As during past visits, he slept on a full bed just a few feet away from a stranger. His roommate developed a cough in early March, just as COVID-19 cases in South Florida began to climb.

On March 17, the company moved him to a single room after a request from his lawyer. Miami-Dade Mayor Carlos Gimenez shuttered hotels to stop the spread of the virus four days later, with an exception for stranded travelers. A spokesperson for the mayor said the county is not privy to agreements between hotels and cruise companies.

Crew members with COVID-19 began to arrive at the Plaza Hotel from the cruise ships and occupy rooms on the fifth floor, Córdova said. Their meals were delivered to their rooms. Crew members staying on the third floor were guarded by security guards who knocked on their doors several times per day to make sure they were there. The hotel staff didn’t use masks until mid-April, Córdova said.

By then Peru had closed its airport, except for repatriation flights.

On April 7, Córdova turned 48 years old. His family sang feliz cumpleaños over the phone once in the morning and then a second time at night.

Five charter repatriation flights for cruise ship workers have taken off from MIA bound for Peru carrying 1,273 people since April 28, according to data from the Miami-Dade Aviation Department. But Córdova has remained largely trapped inside a hotel, with no news about when he will see his family again.

After seven months away from home, he feels forgotten.

“I try to be positive for my family, for my kids, always try to show them that I am ok,” he said, breaking into tears. “I never was thinking to be like this, three years suffering because they didn’t provide me the proper care.”

He paused.

“No existimos para ellos,” he said. We don’t exist to them.

‘It’s a life’s work that was lost’

He sleeps on the full bed closest to the window. Though it doesn’t open, it provides a bird’s eye view of other people’s daily lives, a thin tether to normalcy. Below, Miamians walk past the row of low budget hotels and shuttered aviation offices on NW 36th Street to get to the bus stops.

His black suitcase sits ready to go, next to the TV stand, below the hotel’s black-and-white photo of a lighthouse hanging on the wall. A brown, accordion folder holds his medical records, organized by date, safely stored inside a brown satchel next to the suitcase.

He picks up breakfast at the cafeteria on the first floor before 9 a.m. and returns to his room to eat at the table with two chairs between the bed and the window. He has carefully placed on the table two images of El Señor de Los Milagros, an important spiritual symbol for Peruvian Catholics, gifted to him by a friend before his surgery. Planes glide in and out of parking spots along the runway across the street. The air conditioner hums.

His phone has long stopped working, so he relies on his laptop to communicate with family. He calls his wife most mornings to hear updates about her, his kids and his elderly parents; he rarely has updates to share. It was over one of these calls he learned that his uncle died of COVID-19 last month.

After sitting for more than an hour, the ache in his back that he has become accustomed to sharpens, and he has to lay down on his left side and wait for the pain to subside, a post-operation reality that makes it hard to do even administrative work. At noon he picks up a meal ticket from the front desk and exchanges it for lunch in the cafeteria. Then back up again to the table by the window.

He still can’t walk up or down stairs. Córdova is suing Royal Caribbean for compensation from his permanent injuries and lost wages.

He is careful about what he asks his extended family to send him money for: toothpaste is a necessity, he reasons, but a haircut isn’t. His dark hair, parted on the side, now covers part of his forehead. He does laundry in the bathtub using hotel bar soap.

Oftentimes he has lost his appetite by dinner, so he trades in his final meal ticket for bottled water instead of food. He calls his kids to hear about their days of virtual learning. His son, 16, finishes high school this year. He and his wife started an insurance plan for his college tuition seven years ago, depositing what they could each month. They drained the account after Córdova injured his back on the cruise ship to keep their house, a failure Córdova can’t talk about without breaking into tears.

“It’s a life’s work that was lost, a family project that was lost because of my illness, my health situation,” he said. “Dreams, I have dreams, my wife does too. I try not to think. My focus day to day is on my wife and my kids, I maintain my mind distracted so I don’t get more ill.”

Home

The first crew repatriation flight from MIA to Peru took off on April 28. Another left on May 5. On May 6, Meister, Córdova’s lawyer, sent an email to Royal Caribbean asking that he be put on a flight home as soon as possible. No response. On May 11, she sent another email asking he be sent home. No response. The next day, another flight full of crew members left bound for Peru. And another on May 19.

Córdova waited for word about when he could go home.

The water at the hotel shut off for two days in late May, preventing any hand washing. The hotel didn’t have any sanitizer. Thick, gray mold covered parts of the wall and ceiling in his room, photos show. He changed to a different room, but found cockroaches and the same thick, gray mold clinging to the air vent. Royal Caribbean sent him three disposable masks.

“The condition at the hotel is bad,” Meister wrote in an email to the company on May 22 asking he be transferred to a better hotel. “Again, Mr. Córdova would like to go home to Peru. Please include him on the next charter flight to Peru.”

Another crew repatriation flight for Peru left MIA on June 13. Córdova wasn’t on it.

On June 25, Córdova’s emails to the Peruvian embassy were finally answered. There was a seat for him on a June 27 flight from MIA to Lima if he wanted it for $350. Meister sent the registration link to Royal Caribbean with “URGENT” in the subject line and asked for the company to confirm the flight as soon as possible.

A representative from the company said she would look into it. The next day, Meister followed up. No response. She followed up again. No response. The flight took off without Córdova on June 27.

“That gave me a lot of anxiety,” he said. “That was my hope to be able to see my family again.”

Royal Caribbean continued to schedule doctor’s visits and physical therapy appointments for Córdova in Miami, appointments he would be attending in Peru or flying back to Miami for if it were not for the pandemic. After missing the repatriation flight coordinated by the embassy, he developed a stomach infection and received treatment for it. The company sent prescriptions to the hotel.

On June 30, Royal Caribbean finally transferred Córdova to a different hotel: the Clarion Inn & Suites in Miami Springs, where at least eight other crew members are living. But a mid-July crisis approached: His tourist visa expired on July 14.

In a final plea to get Córdova out of the country before he violated the deadline, Meister sent an email to the company on July 13 again requesting he be flown home and not left in legal limbo.

“Due to the COVID 19 pandemic, many countries have closed their airports/borders,” the company said in an email, directing Córdova to the “US immigration website” or embassy to sort out his immigration status. “Peru is one of the countries that had experienced flight suspensions. We await to learn the date we can arrange travel to return Mr. Cordova to Peru.”

Córdova worries about whether he will be able to return to the U.S. to see his doctors in the future after overstaying the visa.

“When we are working, we give everything, we give everything of ourselves so that our work will be done well, so that the company also will give good service to the passengers who come on the ships,” he said. “We push ourselves 100% and even more. I have given many more than my work hours and with a lot of love for the work. It’s frustrating to see that when you fall ill, they don’t assist you in the slightest.”

August 5 marked three years since Córdova had to stop working, a discouraging anniversary he spent alone in his Miami hotel room.

He wishes he could have done the back surgery sooner, so that maybe he could be further along in his recovery, closer to the day when he might be able to work again.

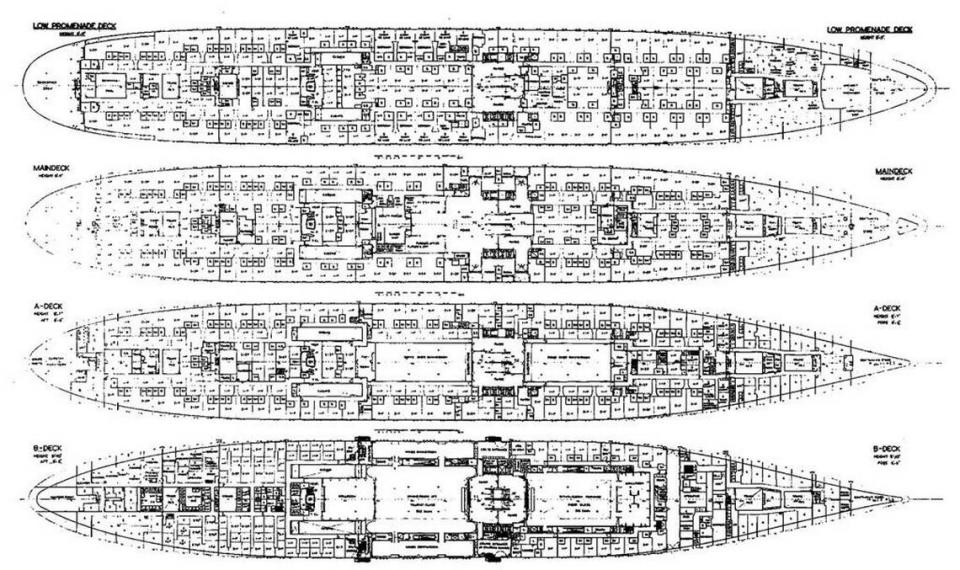

To pass the time he studies cruise ship plumbing plans he finds on the internet.

“You know inside the cabin the ceiling looks just like a normal ceiling?” he said. “There are thousands of tubes in the ceiling. You have to know where to open it. On the plans there are thousands of lines with codes, you have to know how to read it. I could do it pretty well to be able to solve problems.”

Right now his biggest problem is getting home. And there’s no plan he can study to solve it.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies