Many Florida Seniors Did Not Evacuate Hurricane Ian. The Toll Is Devastating.

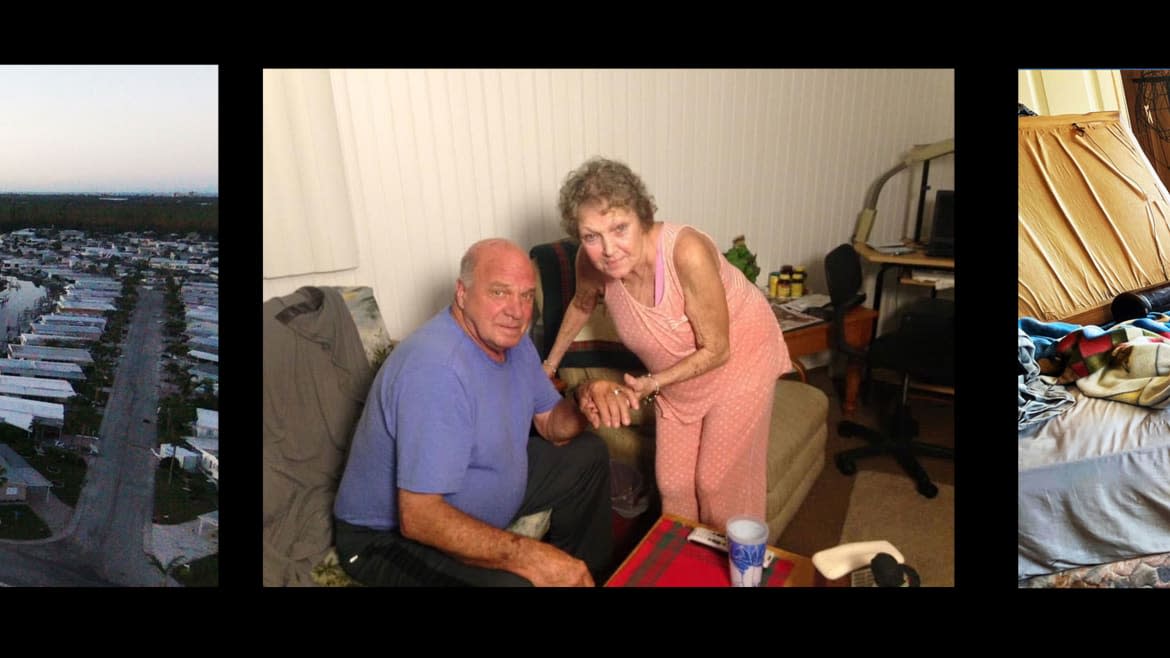

It’s been three days since Richard “Toby” Freeman last saw his wife after volunteer rescuers pulled her off a damp mattress cluttered with their belongings in their hurricane-flooded mobile home. It’s the longest they’ve been apart since he can remember. And he’s preparing to never see her again.

Sitting in a hospital room 125 miles away from the couple’s butter yellow home in Bayside Estates, a predominantly older community situated around canals in Fort Myers Beach, the 77-year-old is processing losing essentially his entire life in one day. Hurricane Ian took most of its force out on the Freemans’ southwestern corner of Florida, sending storm surge into their home so strong it ripped their refrigerator from the wall and turned it on its side. Their apartment looked like a child’s bathtub filled with toys—except it was all their possessions.

The water rose so quickly, up to his armpits, that he covered their bed with couch cushions and helped put his 73-year-old wife, Karen, and their old Shit-zu, Scrappy, on top. They lay there as the water pushed them up until their faces almost touched the ceiling. At one point, he said, Karen turned, locked eyes with him, and said, “I don’t think I am going to make it through this.”

That is Toby Freeman and his dog, Scrappy, after being evacuated and taken to a shelter.

After what they went through, he’s still not sure if she will.

She was taken across the state to Cleveland Clinic Tradition Hospital in Port St. Lucie. Doctors think she might have had a heart attack, Chris Freeman, Toby’s daughter, told The Daily Beast. She’s anxious, keeps reliving the 24 hours that they spent on that mattress, and her breathing is sounding worse each day, the family said.

Even before the storm, Karen was basically immobile due to five back surgeries, a broken femur, and a leg injury, her husband said. Toby, a tall, gruff, former truck driver, also can’t lift his left arm much above his waist after a dump truck tire exploded and hit him two years ago when he was working part-time. Now retired, he’s become even more of Karen’s rock. She’s my “favorite piece of junk,” he joked. They spend most of their time watching TV and ordering what they need from Wal-Mart. Both have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, meaning they struggle to breathe and rely on oxygen machines.

Like so many others in Lee County and in other Gulf communities, the Freemans chose to stay in their home and ride out the storm. Having lived through so many others, including Michael, they weren’t too concerned and so they stayed put. Ian was supposed to smack farther north, near Tampa, Freeman and other older residents who did not evacuate told The Daily Beast.

Overview of flooded Bayside Estates

Officials in Lee County, where nearly 30 percent of the population is over 65, delayed issuing mandatory evacuation orders in the days before Ian struck, despite The National Hurricane Center issuing dire warnings that it could submerge the area with up to seven feet of storm surge. Then the Category 4 hurricane, one of the strongest to ever strike the U.S., turned and made landfall Wednesday on a barrier island close to the Freemans’ mobile home park, devastating it, many others, and retirement communities nearby.

That decision to delay is now under scrutiny even as Gov. Ron DeSantis, FEMA, and even President Biden have defended the call. In an update on Monday, Florida’s emergency management chief said that “all evacuation orders…are handled at the local level” and that Lee County’s emergency management director “made the best decisions based on the information they had at the time.”

Freeman, other residents, and search and rescue groups disagree, saying that there was a lack of urgency until it was too late.

“They held off too long,” Toby Freeman said. “We got a call at some point close to it hitting that if you got somewhere to go, go, or hunker down. It was ‘stay in your house’ at that point because there was nothing to do, nowhere to go.”

Wife in ‘Shock’ After Watching Disabled Husband Die in Hurricane Ian Floodwaters

More than half of residents in Fort Myers Beach, where the Freemans live, are elderly, and as the death toll rises and rescues continue, there is an increasing demand to know why officials did not do more to get seniors out of their homes. The Daily Beast spoke with 10 older residents, family members, and several search and rescue groups, who detailed why they stayed behind, how they got information about the storm, and the harrowing experience of trying to survive and get out after it hit. All of the seniors said they did not know it was going to be so bad and weren’t really tracking the hurricane, highlighting another challenge that disaster managers face when coordinating and organizing wide-scale evacuations, experts told The Daily Beast.

As of Monday afternoon, at least 100 people have died as a result of the historic hurricane, CNN and other outlets have reported, though the official death toll is still 68. Fifty-four people died in Lee County, the sheriff’s office said Monday. Officials have decided to close Fort Myers Beach to “preserve crime scenes” as they continue to look for the dead, Mayor Ray Murphy said.

A boat on top of a mobile home in Bayside Estates

In releases from sheriffs and coroners’ offices across various counties, the majority of the deceased, so far, are elderly, “found drowned.” In Volusia County, near Daytona Beach, a 68-year-old woman was swept into the ocean by a wave. Waiting to be rescued with his wife, a 67-year-old man fell in his home “and could not get up before the water level rose over him.” In Sarasota County, a 94-year-old man and an 80-year-old female stopped breathing after their oxygen machines gave out due to power outages.

As of Monday, a task force of responders had rescued about 2,350 people by land, air, and sea, largely in the hardest-hit areas along the southwest coast, Florida’s Division of Emergency Management told The Daily Beast. Lee County officials said Monday they’ve helped 800 residents so far. On top of that, a spate of volunteer and citizen-led rescue crews have extricated hundreds more, combing rubble-filled, flooded streets in pick-up trucks, boats, canoes, and whatever other vessels they could get their hands on.

Three volunteer and citizen-run search-and-rescue crews on the ground told The Daily Beast that they have predominantly been saving and helping older residents. Two groups, Patriot Emergency Response team, and 999 Rescue, grabbed 30 to 40 people from Bayside Estates alone, including Toby Freeman and his dog, lead dispatcher Lauren Trahan told The Daily Beast. Late Wednesday night, Facebook groups exploded with desperate messages from people looking for their parents and loved ones, or asking for help rescuing them and those with disabilities who were cold, trapped, or without electricity. Rescuers had stories of people plucked from cars floating down flooded streets, of those with dementia who had no idea where they were, of an older woman who didn’t know about the storm until a torrent of water burst through her wall, of elderly residents who fell and hit their heads or hurt their backs, of a 59-year old man in a wheelchair stuck with his 90-year-old mother and her eight cats.

“They were very scared and shook up,” Trahan, who stays on the line with crews as they respond to calls, said. “Some didn’t know who we were, they just kept saying everything was wet and they didn’t know what happened.”

Toby Freeman, she confirmed, had run out of oxygen by the time a crew got their high-water vehicle into his community. His breathing was “very labored” and he was “to a point of onsetting hypothermia.” Toby refused to leave when the first crew showed up Friday morning, choosing to stay in case he’d be separated from his dog Scrappy at a shelter, he said. He stayed put in his soaked La-Z-Boy recliner, cold and in soiled underwear that ended up causing him to get sores.

“At that point if I had to pee I did, and same way with the bowel movements,” he said. “But luckily I hadn’t eaten a lot.”

Data from CrowdSource Rescue, a volunteer nonprofit, shows it received and helped search-and-rescue crews respond to 865 requests for help, and 519 of them were older residents.

“We’ve been rescuing almost exclusively seniors in this storm, which is unique. It feels like we’re rescuing half the country’s grandparents,” Matt Marchetti, CrowdSource Rescue’s co-founder, told the Daily Beast. “The general consensus was it was going to hit Tampa and then it shifted south and people then only had two days. Our thinking is that a lot of seniors couldn’t or didn’t evacuate.”

The inside of the Freemans’ mobile home in Bayside Estates

But for those older residents like the Freemans, who live independently, choosing to leave is often a difficult or unimaginable choice, no matter how much their children plead with them. Many choose not to leave their homes because it’s harder for them to move. Often on fixed incomes or social security, the cost of gas, a hotel, and extra food is too expensive, or they don’t have access to transportation. Many have vital medication and equipment for health issues like dialysis, diabetes, and breathing machines, which require electricity.

And when it comes down to it, seniors often just don’t want to leave. They feel like their home, pets, and belongings are all they have, they, research, and experts have said.

“This sense of home and place is a recurring theme for hurricane-affected older residents,” said Sue Ann Bell, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan who studies aging and disasters. “People worked 40 to 50 years to afford this home and the thought of leaving it, leaving their treasured mementos, is almost like leaving your sense of self.”

That was the case for Mary Rooker, who is 96 and lives in a retirement community in Fort Myers. Her husband of 77 years, Calvin, died last May and she convinced her children to let her come back to Florida last week because she wanted to be where she could feel him, and that was in their condo.

“I was in pieces after he died and I felt I had to come back and settle things,” she said. “If I didn’t, I didn’t think I’d ever be happy.”

Hurricane Ian Showcases GOP’s Disaster Aid Hypocrisy

Days later, Ian rendered the inside of their home unrecognizable, and she’s been living in the community’s rec room, which still has no electricity or running water. Rooker chose to ride out the storm with a few of her neighbors in a rec hall because, she said, “it’s just difficult to evacuate.” She also had a terrible experience at a Lee County shelter during a storm a few years ago that she says still gives her “nightmares.” There was not a lot of food, no privacy, toilets were overflowing, and by the end of their stay, they were rationing water.

Volunteer Search and Rescuers Chad Smith and Nevin Young escort an older resident off Sanibel Island Friday morning

Years ago, she and her husband used to drive as far as Alabama to secure a hotel room to ride out hurricanes. As she’s gotten older, her options are even more limited, and being in a shelter makes her feel like a caged animal. So for the past few days, she’s been living in the hall, sleeping on a pool chair with a blanket alongside about eight others, she and Ale Palacios, a volunteer who’s been bringing food, water, and generators to the group, told The Daily Beast.

“It’s hard on my back and my hips are sore but it’s someplace to lay my head,” she said. “But we’ve got our lives and that’s the most important thing.”

In his hospital room, after choking up when a nurse snuck in Scrappy for a visit, Toby Freeman said something similar. There’s nothing from his house that he expects to save, though he hopes that some jewelry that belonged to Karen’s family (a ruby ring from her great aunt that was sitting on her dresser), family photos, and his autographed photos and cars from race car driver John Force somehow made it through. Everything else, down to his driver’s license, is lost.

“There’s nothing that even says his name on it,” said his daughter, who’s been trying to figure out how to fly him to be with her in New York once he’s released from the hospital.

Bayside Estates might also cease to exist, a fate that other communities are also grappling with. In a note to residents, Bayside Estates said that their power grid will take months to rebuild and they aren’t sure the park’s infrastructure will even be salvageable. Their homes and streets are filled with a muck made of sewage, oil, and gasoline, and mold spores have already started to spread, a member of their board of directors told residents in their Facebook group.

“We question the viability of the park going forward,” the post said. “There would be a massive amount of work and an extreme amount of money to just get the buildings and outdoor areas cleaned up and restored. The canals would all have to be cleaned. Sea walls may also have damage.”

The mattress where the Freemans rode out the storm

Toby Freeman doesn’t think he’d go back anyways, he’s hellbent on moving forward, even if he has to do it alone. What choice does he have, he asked?

“I have to continue with my life,” he said. “I’m not going to let this get me. I’ve made it this far.”

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies