How Rocky Balboa Become Philadelphia's Signature Superhero

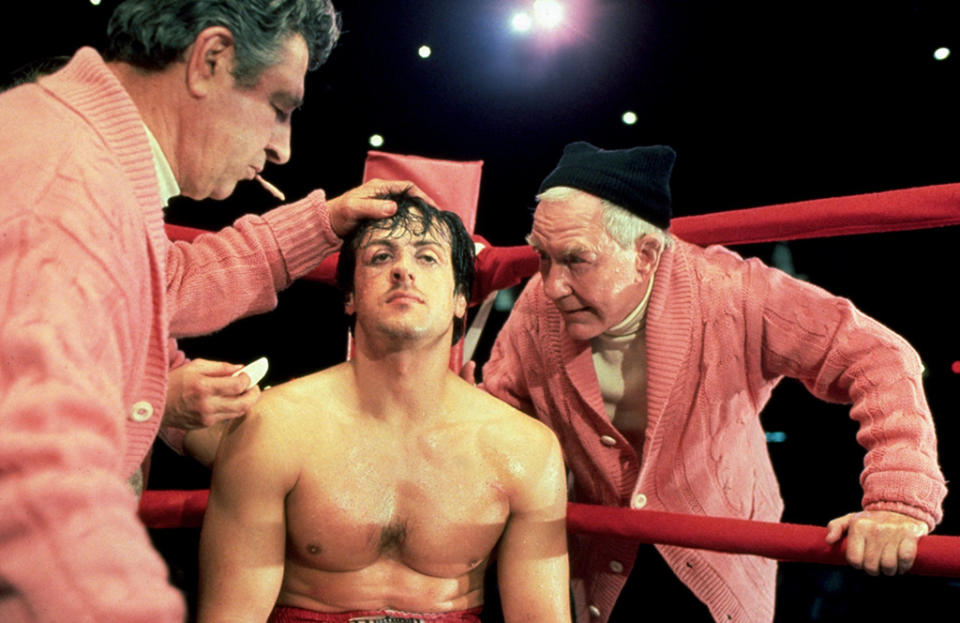

Sylvester Stallone in the original ‘Rocky’ (Everett)

In 1986, when I told my nephew that I was moving to Philadelphia, the L.A. high-school junior asked, “Is that near Boston?”

“It’s between New York and D.C.,” I replied. I hummed the famous opening theme, “Gonna Fly Now” and raised my fists triumphantly above my head. He immediately nodded. “Right, Rocky.”

Is there any other film figure so deeply linked with one city? I wondered then — and I still do now, as the Italian Stallion passes the boxing gloves to the son of his onetime rival Apollo Creed in director Ryan Coogler’s new drama Creed that’s hitting theaters on Thanksgiving. From The Philadelphia Story to Trading Places, the Philly story onscreen has mostly been about blue bloods and blue collars initially at odds, but ultimately finding common cause. Rocky is different. “Stallone made the Horatio Alger story, tarnished and suspect during Vietnam, credible again,” film historian Jeanine Basinger told me in 2001.

I arrived in Philly a decade after Rocky bested All the President’s Men and Network to win the 1976 Best Picture Oscar. By 1986, Rocky II, III, and IV had been released and the eponymous pug created and portrayed by Sylvester Stallone had been canonized as the city’s secular saint. He was as essential a part of the urban mythos as Benjamin Franklin.

Watch the ‘Creed’ cast talk Philly cheesesteaks:

I couldn’t buy a piece of fruit in the Italian market without being shown the exact spot on 9th Street where some guy threw Rocky the apple in the original movie. (I later found out this moment was unscripted: An anonymous green grocer threw it, and Stallone made the catch without missing a beat.) Nor could I go to the Philadelphia Museum of Art to see the Cezannes (how do you like them apples?) without overhearing someone say, “This is where Rocky runs up the stairs.” According to Time, the art museum steps rank as the second-most-iconic film location in all of cinema, after the Field of Dreams cornfield. (This No. 2 ranking, by the way, was denounced on every Philadelphia radio call-in show.) If I had a nickel for every wise guy that found out that I reviewed movies for the Philadelphia Inquirer and that challenged me to recap the fights in every Rocky movie, I could probably buy a Cezanne. There are guys in Philly who can give you color commentary on every bout as if these fights actually happened.

By the time of the release of Rocky V in 1990 — generally considered the nadir of the franchise — friends visiting the city wanted to know everything Rocky. My sportswriter colleagues Ray Didinger and Glen Macnow (who voted Rocky No. 1 in their Ultimate Book of Sports Movies) unearthed one favorite piece of trivia: Sylvester Stallone spent so much time punching the frozen sides of beef in the training scenes that his knuckles are permanently disfigured. Another: Dan McQuade, intrepid reporter at Philadelphia magazine, clocked how many miles Rocky would have run in the training montage in Rocky II — and it was more than 30!

Related: 72 Hard-Hitting Facts About the ‘Rocky’ Movies

A factoid that shocks many Philadelphians is that original director John Avildsen, working with a shoestring budget of $1 million, figured that Rocky would play the lower half of a double bill. And who knows whether the Museum of Art steps would have factored into the film at all had not Steadicam inventor Garrett Brown, whose revolutionary camera-stabilizing harness puts the audience in Rocky’s skin, shot a demo reel of his wife running up the museum steps. When Avildsen saw it, his first questions were, “Where are those steps?” and “Want a job?”

While everyone in Philadelphia loved Rocky, there were some who did not care for the 12 ½-foot statue of Philly’s favorite boxer commissioned by Stallone for Rocky III. Initially, it stood at the top of the Museum of Art steps. Some museum officials and members of the city art commission deemed it a movie prop, not a piece of art, and it was moved to the sports complex in South Philadelphia. For many years, it welcomed visitors to the Spectrum where the Sixers played.

The Rocky statue in Philly (Photo by Gilbert Carrasquillo/FilmMagic)

After much political back-and-forth in 2006, the statue was returned to the museum — not at the top of what is now universally known as “the Rocky Steps,” but at the bottom of the 72 granite stairs, just a little to the right. This took place in September, a few months before the release of Rocky Balboa, the sixth, and ostensibly last, film in the franchise.

In 2006, two of my Inquirer buddies, Mike Vitez and Tom Gralish, spent a year at the Rocky Steps, which over the years has improbably become a pilgrimage site, Philadelphia’s Lourdes, where people come to pay tribute to others and celebrate triumphs from the birth of a child to a victory over cancer. The resulting book, Rocky Stories, is as inspirational as any Rocky movie. “Stallone had no idea running the steps would become the iconic rite it has become,” Vitez said last week. As the actor/director himself wrote in the foreword to Rocky Stories, “You know, you can’t borrow Superman’s cape. You can’t use the Jedi laser sword. But the steps are there. The steps are accessible. And standing up there … you are part of what the whole myth is.”

As an adopted Philadelphian, I fully expect that in a few years that next to the Rocky statue, there will be one of Adonis Creed, the young boxer played by Michael B. Jordan who’s mentored by Stallone’s now grizzled Balboa, in the triumphant return of the series. I am basing this not only on my own reaction to Creed. When I left the screening, wiping tears of joy from my eyes, I saw studio security guards weeping too. And they weren’t even from Philly.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies