‘High-level chess’: How Biden is navigating his relationship with Mexico’s President ‘AMLO’

WASHINGTON – When President Joe Biden tapped Vice President Kamala Harris in March to address the surge of migrants seeking to enter the United States, he also enlisted her help to solve a thorny diplomatic problem: improving relations with Mexico.

A smoother relationship with Mexico's President Andrés Manuel López Obrador could be a game changer for efforts to stem the flow of migrants. But López Obrador, a populist leader also known by his initials AMLO, has been slow to warm up to Biden and his team. Harris will have a chance to make inroads in a virtual meeting Friday and a planned visit in June.

It probably won't be easy.

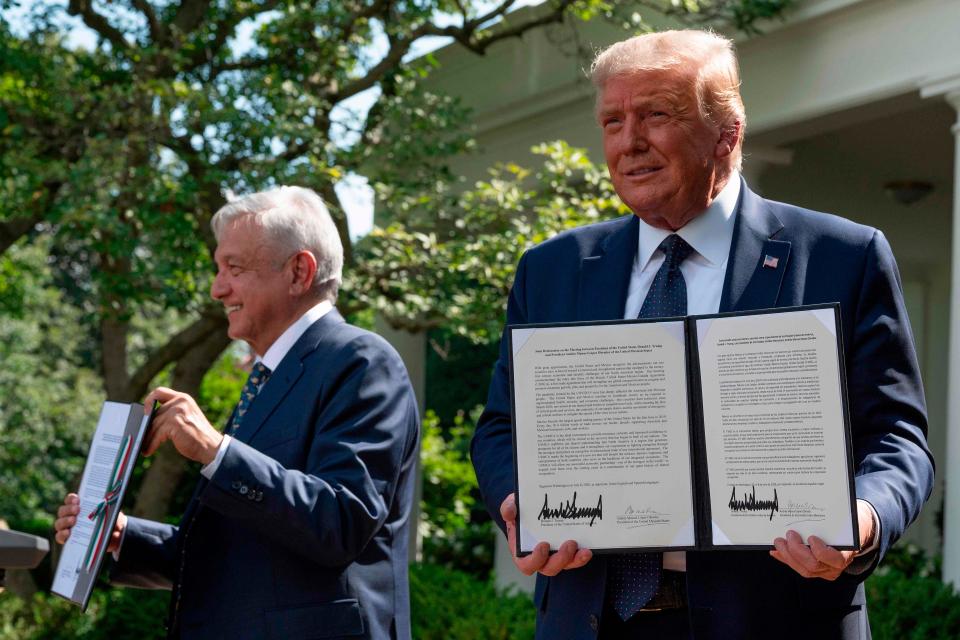

AMLO's lack of enthusiasm for close ties with Biden was evident months before the Democratic president took office. Last summer, AMLO, who had forged an unlikely friendship with President Donald Trump, traveled to Washington to mark the enactment of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). He lavished praise on Trump for "respecting" Mexico but snubbed senior Democrats and skipped the chance to meet then-candidate Biden.

In a more pointed diplomatic jab, AMLO was one of the last foreign leaders to congratulate Biden on his election win and even as he did so, he issued a chilly salvo making clear he wanted the incoming president to stay out of Mexico's affairs.

More recently, López Obrador piled on as Republicans blamed Biden for an influx of migrants, particularly unaccompanied minors, showing up at the southern border, undercutting the Biden administration’s defense that the increase was the result of a seasonal surge compounded by the coronavirus pandemic and a series of natural disasters.

“Expectations were created that with the government of President Biden there would be a better treatment of migrants,” AMLO said in a March 23 press conference. “And this has caused Central American migrants, and also [migrants] from our country, wanting to cross the border thinking that it is easier to do so.”

But the Biden administration has a huge stake in better ties as he and AMLO look to resolve a migration problem that could damage both of their presidencies.

In Friday's virtual chat and a meeting June 7-8, Harris takes on diplomatic negotiations with Mexico and the so-called Northern Triangle countries, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, to address the root causes of migration – a role Biden similarly played under former President Barack Obama.

Harris is seeking Mexico's continued cooperation on immigration enforcement amid a surge of illegal border crossings after Biden reversed Trump-era, hardline immigration policies, some of which were brokered with AMLO.

The vice president also pitched Mexico on a regional approach to limit migration by investing in anti-corruption and economic programs in Central American countries as well as look for commitments on climate change and labor protections.

"We must continue to do our work in a way that is both bilateral and multilateral. It is our intention and it has been a guiding principle of us that we are going to do this work in a way that internationalizes our approach," Harris told AMLO. "That reaches out to our allies, to our friends around the globe in the mutual interest that we all should have to address the root causes in the Northern Triangle."

AMLO acknowledged that "relations were not completely positive between our countries" when he first met with Biden in March, but assured Harris the U.S. could count on Mexico when it comes to migration policy.

'America is back'

Biden has promised a sharp break from his predecessor's foreign policy, trumpeting the message "America is back."

That pledge has done little to win over AMLO, who established a rapport with Trump despite the Republican president’s 2016 campaign rhetoric attacking Mexican immigrants as "rapists and murderers" and his promise to build a "big, beautiful wall" along the southern border – which he said Mexico should pay for.

While Trump and López Obrador made strange bedfellows, the pair found a balance in a transactional approach on immigration. AMLO would help stem the tide of Central American migrants, including allowing asylum seekers to wait in Mexico border towns for U.S. court appearances, and Trump would turn a blind eye to Mexican domestic issues.

David Rothkopf, author of “Traitor: A History of American Betrayal from Benedict Arnold to Donald Trump,” said he doesn’t expect Biden's relationship with AMLO to be as easy as it was under Trump as it will be more complex.

“AMLO’s populist, nationalistic thrust is one that is very much tied to the idea of shaking off the influence of the giant to the north,” Rothkopf said. “And he’s essentially adopted a Trumpian lens through which to see the relationship...which translates to, ‘we don’t want you to call us out on our problem areas.’”

The number of migrant encounters at the U.S.-Mexico border climbed 71% in March, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection data, making it the busiest month in nearly two decades. The April numbers, which have yet to be released, are expected to be even higher.

As the numbers swelled, Democrats and Republicans alike criticized overcrowded facilities where migrants are being held as officials scrambled to house them in sites large enough to accommodate COVID-19 restrictions.

In March, the U.S. struck a deal with Mexico, Honduras and Guatemala to tighten their borders and provide more troops to curb the tide of migrants. Mexico doubled the number of its detentions and has maintained a deployment of 10,000 security personnel at the border.

Mexico also agreed to close its northern and and southern borders to non-essential travel – a step the country had never taken in the year since COVID-19 spiraled out of control. Barely an hour later, foreign secretary Marcelo Ebrard confirmed the U.S. agreed to “loan” Mexico 2.5 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, which has yet to be approved for federal emergency authorization.

Biden has also revived a strategy he pursued as vice president: emphasizing a diplomatic approach by addressing the root causes driving migrants to leave their countries and head north. In remarks to the Conference on Americas this week, Harris outlined the root causes as corruption, violence, poverty as well as a lack of economic opportunity, climate resilience and good governance.

Biden is seeking $4 billion in aid to Central American countries over the next four years, funneling a majority of the money to community organizations rather than government officials to avoid concerns over endemic corruption. Harris announced $310 million in humanitarian relief and food aid for Northern Triangle countries during a virtual meeting with Guatemalan President Alejandro Giammattei in April. Trump cut all foreign assistance to Northern Triangle countries in 2019.

A game of ‘high-level chess’

Joe Heyman, director of the Center for Inter-American and Border Studies at the University of Texas at El Paso, described diplomatic moves between the U.S. and Mexico as “high-level chess between one side that has a bunch of queens and the other side that has a bunch of pawns.”

“A pawn can take down a queen, and Mexico has some power,” Heyman said. “But the United States has this incredible economic threat. There isn’t a place in Mexico that is not completely tied to the U.S. economy.”

The countries’ economies are deeply intertwined. In 2019, Mexico surpassed China as the United States’ top trading partner. More than $677 billion in goods and services flow back and forth annually – roughly $1.8 billion per day, according to the Office of the United States Trade Representative.

The United States buys roughly 80% of Mexico's exports, accounting for about 39% of Mexico’s gross domestic product, according to a June report by the Congressional Research Service. The U.S. is also Mexico’s most important source of foreign direct investment, with $100.9 billion invested in 2019 largely in the manufacturing, finance and insurance sectors.

Meanwhile, Mexico buys more U.S.-made goods than any country after Canada.

Even with restrictions on “non-essential” travel at the U.S.-Mexico border, close family and cultural ties have meant frequent border crossings by U.S. citizens, legal permanent residents and those with work or student visas.

Immigration, which has emerged as an Achilles heel for Biden in his first months, gives Mexico leverage as AMLO looks to court the U.S. on foreign investment, more coronavirus vaccines and funding for the Mexican president’s own re-forestation program in exchange for an eventual six-month U.S. work visa.

More: Police help Border Patrol catch migrants, which is bad policy, experts say

More: Biden administration to house migrant teens at overflow facility in Texas closed under Trump

AMLO is known for his populist style – though unlike Trump, he ran as a leftist politician. Both men consider the media an enemy and lash out at opponents using unflattering names, which often stick.

Within Mexico, the populism that has come to define AMLO's political brand was initially symbolic.

One of his first moves as president was to put Mexico’s luxurious presidential aircraft up for sale; austere AMLO would fly commercial. (Three years later, AMLO hasn’t flown in the made-to-order Boeing 787 as he promised, and it has yet to sell.)

He eschewed the presidential residence, Los Pinos, and converted the mansion into a museum open to the public. After initially residing in a town house on the city’s south side, he moved into an “apartment” inside the centuries-old National Palace, located in the heart of Mexico City’s Zocalo – the site of his notorious protest against a “stolen” election in 2006.

When AMLO paid a visit to the northern border city of Juárez, he addressed business leaders at one of the city’s ubiquitous maquiladora factories and brought factory workers off the production line to listen in alongside them. His move to raise the minimum wage at the border to about $9 a day fell flat; most workers already earn slightly more than that.

But his populist moves have been more than tinsel: Analysts say AMLO has been systematically weakening institutions key to Mexico’s hard-won democracy.

Early on, AMLO decreed that no one in government could earn more than the president, and he would take a salary no greater than $5,540 per month. His administration slashed thousands of government jobs and reduced wages for others. Analysts say the austerity program has hurt economic growth ― the country’s GDP contracted 0.1% in 2019 – but it has also knee-capped institutions designed to keep presidential power in check.

Heading into the June 6 midterm elections, AMLO has sought to discredit the country’s electoral institute known as the INE. In April he backed a decision by the Senate, where his party holds more seats than any other, to extend the Supreme Court chief justice’s term for two more years – a move that critics say could position AMLO to propose re-election for presidents, who can now serve one six-year term.

AMLO recently bristled at the State Department's annual human rights report, which warned of Mexico's gang violence and limits on press freedom and criticized the country's prison and detention center conditions

“We can’t opine on what happens in another country so why is the US government opining on questions that are purely Mexican matters?” he asked.

Increases in migrant flows have resulted in another attempted crackdown by Mexican immigration officials, especially in the country’s south, according to Sergio Martin the head of mission for Doctors Without Borders in Mexico.

“These actions will not stop migration on the other side," he said. "They are affecting and they are exposing more violence to the most vulnerable population among the migrant population.”

Mexico has already been under the microscope for its treatment of migrants. Local police officers were implicated in the massacre of 19 people, most of them Guatemalan migrants, in January just south of the Texas-Mexico border. The killing of a Salvadoran woman in the resort city of Tulum on March 27 unleashed protests nationwide. The following day a soldier shot and killed a Guatemalan migrant near the border with Guatemala when he attempted to evade a checkpoint.

López Obrador's supporters are increasingly wary of U.S. intervention under Biden, particularly on human rights concerns and climate change. Some supporters openly backed Trump in the 2020 U.S. election. The Mexican president's allies often see any support for Biden as pleas for U.S. meddling in Mexican matters.

“When people comment on Biden, they always relate it to Mexican politics,” said Brenda Estefan, a former security attaché at the Mexican Embassy in Washington. “They actually take Trump’s words and say things like ‘Sleepy Joe,’” she said, relating what she sees in social media reactions to her international affairs commentary. “People who are for AMLO are against Biden."

But Biden has a personal history with Mexico that stretches across his tenure in the Senate and as vice president when he visited Mexico four times.

Obama tasked Biden with confronting a similar crisis in 2014, when officials saw more families and unaccompanied minors coming from Northern Triangle countries showing up at the border. The then-vice president helmed the administration's $1-billion Alliance for Prosperity plan, which sought to address the root causes of migration and invest in police training and judicial reforms in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

Biden’s experience makes him well-positioned to restore trust, said Anthony Wayne, U.S. ambassador to Mexico from 2011 to 2015.

"He oversaw the high level economic dialogue with Mexico, which was the most productive mechanism we had for dealing with a lot of interrelated and complicated economic and border management issues," Wayne said. "The big challenge right now is to build a trusting relationship and there's some really difficult issues to work through in that relationship."

Harris, for her part, convened a Cabinet secretaries meeting to discuss how each agency can play a part and has weekly lunches with Secretary of State Antony Blinken, a White House official said. Harris also regularly consults Biden on his own experience as Obama's point person on diplomatic talks on immigration, the official said.

Harris is "realistic" and understands that "if it were a problem that could've been solved overnight, it would've been solved a long time ago," according to the official.

Symbol of Guadalupe

During his first virtual meeting with his Mexican counterpart as president, Biden invoked the Virgin of Guadalupe, a cultural touchstone for millions of Mexicans and a sacred symbol of devotion in Biden’s Catholic faith.

Biden conceded the United States and Mexico "haven’t always been perfect neighbors with one another," but pledged to treat Mexico as an equal partner. He also expressed admiration for its culture.

“As a matter of fact, I still have my rosary beads that my son was wearing when he passed,” Biden said, speaking of his late son Beau as he pointed to the rosary beads from her namesake shrine affixed to his left wrist.

The move was an unmistakable appeal to AMLO and to Mexico where it’s often said, todos somos guadalupanos: we’re all followers of Guadalupe. AMLO named his political party Morena – another name for the virgin – and often speaks of morals and values and cities scripture in his morning press conferences.

"The current paradox is you have a president who does care about the relationship with Mexico and understands the strategic importance of Mexico for the daily prosperity and security of Americans," said Arturo Sarukhan, Mexican ambassador to the United States under former presidents George W. Bush and Obama.

"The big question is does López Obrador take advantage of that opportunity and find common ground with this administration?"

Robert Jacobson, a former U.S. ambassador to Mexico who served as White House border coordinator before she stepped down in April, told USA TODAY that there was "commonality" between the two countries in wanting to address the migrant surge.

"There is an understanding at the root that neither of us can do this unilaterally," she said. "That this is quintessentially the moment in which we have to be working together and working with the countries of the Northern Triangle."

The migration surge is also a concern to many in Mexico.

“There’s no domestic political cost to stopping the flow of migrants,” former Mexican immigration commissioner Tonatiuh Guillén López told USA TODAY.

Guillén resigned as commissioner after AMLO and Trump struck a deal on Mexico impeding Central American migration and later said the AMLO administration conceded too much in negotiations on immigration.

“There was some wiggle room in the negotiations, (but) the AMLO government decided to not confront (Trump) or run any risks. So he assumed a new migration policy,” Guillén said.

More: Joe Biden’s immigration agenda overshadowed by migrant challenges in first 100 days

While migration has vexed several of Biden's predecessors, the issue has only intensified during the coronavirus pandemic, which deepened instability in Central America and forced more migrants to leave their homes.

Benjamin Gedan, the deputy director for Latin America Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center said the AstraZeneca vaccine loan could be a boost for Washington's standing in Mexico.

“Two and a half million AstraZeneca doses is a drop in a bucket, but a very positive signal,” he said.

It could also be a boon for López Obrador, who has been roundly criticized for his handling of the pandemic.

The virtual meeting with Harris could offer some indications of whether she and Biden can put the relationship with Mexico on a better footing.

AMLO is expected to pitch the vice president on financing the expansion of his “Planting Life” initiative that pays farmers to plant 1 billion trees throughout Mexico. AMLO proposed expanding it to Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador during Biden’s climate change summit last month, contending the program would help keep farmers from migrating to the U.S. for work. But he also wants the U.S. to grant six-month work visas and a path to citizenship for those who participate.

Juan Acereto, a former Mexican diplomat in charge of bilateral relations for the city government in Juárez – which sits at one of the U.S.-Mexico border’s busiest crossing points – said that given the economic importance of its northern neighbor, "Mexico can’t cut a single tie with the United States.”

But the first step will be restoring the trust that's been eroded by the last four years, he said.

“The trust that we build can be broken,” he said. “And that trust for the U.S. is so difficult to achieve, because sometimes the U.S. can trust us and sometimes not. And losing Mexico means losing all of Latin America.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How Joe Biden is navigating a rocky relationship with Mexico's 'AMLO'

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies