‘Happiness can be ignited by making something small infinite’: what makes me happy now

It’s a nightmare, a barbaric farce. The city is first taken by Russians, then by Ukrainians, then by Russians again; foreign forces join the struggle, gangster hordes go on killing sprees, thousands are butchered, and a plague engulfs the survivors. It’s Kyiv. The year is 1918.

A young nobody called Konstantin Paustovsky (fisher, paramedic, student) has just arrived with an itch to write. He’s unusual: in the midst of the slaughter he thinks about happiness. Decades later he will be nominated for the Nobel prize for literature, but won’t, of course, get it. The happiness he thinks about is always the wrong kind.

In Kyiv in 1918, for example, Paustovsky believed that the safest, the happiest refuge from the avalanche of catastrophes engulfing his homeland lay in three things: nature, domesticity and intimacy. As it happens, when the Covid pandemic first struck in Australia, it was in a shack in the middle of “nature” that our little family of two humans and a dog first sought refuge. Needless to say, we didn’t live off nature, we didn’t forage, we just lived among the gum trees. We hoped for comfort amid the chaos in small domestic tasks and intimacy, enjoying the mild intoxication that comes from being unencumbered by the unhappiness of the wider world. We “sucked on country pleasures, childishly”, in the poet John Donne’s words in The Good-Morrow.

Related: Dalliance, affair, love, intimacy: how should we approach sex as we age?

Eventually, Donne said, you really need to be weaned off this sort of thing. In the 1950s, Americans, who have a right under their constitution to “the pursuit of happiness”, came up with a similar formula: vacuuming, baking and watching television, they hunted happiness down in close-knit families on decent-sized, leafy acreages. It could be argued they have never been fully weaned off these practices, remaining oddly infantile in their tastes and behaviour to this day.

For a week or 10 days intimacy and the performance of household tasks in the Tasmanian wilderness worked well for us. Then all of a sudden it palled. Something was missing. Like Nimbin, it had an unexpected air of melancholy about it. We had to think again. What sort of happiness was now possible? To be honest, in the wake of the famines, droughts, flooding and wars that followed the outbreak of the pandemic, the question itself began to seem frivolous.

It’s hardly a new problem, although some recent commentators, in their excitement, have declared our sufferings “unprecedented”. They are actually par for the course. Four hundred years ago, for instance, Robert Burton, the author of the monumental Anatomy of Melancholy, was bemoaning the ceaseless reports of “war, plagues, fire, inundations, thefts, murders, massacres, meteors, comets and omens” afflicting England. Yet by all accounts Burton was a cheery chap: writing his encyclopaedic work on every variety of melancholy known to humankind being a brilliant antidote to the condition itself. Art often is, but let’s not forget – that’s not what it’s for. Even the Assyrians, two thousand years earlier, resorted to the arts, if the reliefs in the British Museum are any guide. Despite the ferociously brutal rule of the Assyrians and the endless droughts, floods, plagues and mass slaughter, some people were apparently happy some of the time – falling in love, dancing, writing poetry and composing music for their flutes and tambourines. There they are in the reliefs. How could this be?

Knowing we could die quite soon means each moment is unrepeatable.

Contentment is often within our grasp, but contentment is not happiness and can never be complete in times such as these. You could feel bolts of happiness during the blitz in London, for instance, but could rarely feel contentment. It’s impossible now to be truly content anywhere in the world as Bangladesh goes under water and Brazil is turned into a wasteland. After all, your own sense of ease and tranquillity is always contingent on other people’s.

From time to time, however, even in the direst situation, even knowing what we know about the waves of violence and disease washing over the planet like some cosmic curse, we can certainly be happy – even ecstatically. If the last few years have taught us anything, it’s that happiness and sadness, even misery can go together. I have a friend in Yogyakarta who could not sleep for months during the first Delta Covid wave because of the sirens of ambulances rushing the dying to hospital. Yet there was also happiness: a new grandchild, a blossoming close friendship, reading Turgenev at dusk in the garden – love, in other words. What else? Donne would not have been surprised. Happiness is like being struck by lightning: the storm merely heightens it. Knowing we could die quite soon means each moment is unrepeatable.

It seems to me more and more now that what invites a bolt of happiness to strike is a heightened need to be creative. I wrote and made new friendships, which takes an artist’s minute attention. When the mind is focused on finding a balance between what it feels deep inside itself in the pond of memories and what it sees and hears and even smells, all around it, there is a sudden radiance that has nothing to do with contentment but is happiness.

When the I behind the eye is illuminated in a flash of new perception – of feeling, understanding, resolution – something flares up that I would call happiness. The flash won’t last, of course, that would be unbearable, it will dim, but so what? There will be an afterglow. Our inner selves are like pieces of music, Eva Hoffman writes in her study of time (called Time) – “patterned performances, made up of micromovements, like a gamelan composition”. During isolation one had the time to hone a virtuoso performance.

Related: ‘A massive spiritual shift’: how the mindful movement of qigong can treat addiction

One of the opportunities the pandemic offered us was to consider time afresh. After all, inhabiting time well, rather than befuddling ourselves with notions of either immortality or the pointlessness of everything, is one of the keys to a happy life. It’s not easy. I recognise now that all the things that make us happy happen in time: falling in love, escapes from the domestic, finding paradise, or creating beauty (gardens, paintings, connections). There is, as Hoffman puts it, “a right rhythm and scale of lived experience – of being-in-the-world – which we need to find for ourselves for the sake of our wellbeing”. The rooted kind of existence that became the norm in recent years made it easier to acquire “a right rhythm”, which opened the door to unthought-of happiness, not just fulfilment or pleasure, but something more dynamic: bursts of happiness.

Finding the inner world more reliable than the outer one, some people I know started to dally with Buddhism, adopt rescue dogs and join choirs. The dogs and choirs show promise, I think, while the Buddhist notion of achieving bliss either through eradicating desire or embracing the non-self has never appealed strongly to me. In my experience, wanting, and either getting or deliciously not getting what I’ve wanted, has been the very stuff of life. Besides, I’ve been visiting Buddhist strongholds from Dharamsala to Cambodia for most of my life, but have seen little sign in any of them that the secret to happiness has been found – to tranquillity perhaps, but not happiness. Nor do I even now, in the face of cosmic annihilation, see much point in “living in the moment” like a blowfly or a dementia patient, although it’s a cliche people still toss around. Living in time now seems a more realistic, more rhythmic, more joyful framework for a good life than striving to transcend it in the hope of a selfless immortality.

Actually, what Robert Burton, John Donne and Eva Hoffman all accentuate in their writing and in their lives is the happiness ignited by making something small infinite. Burton’s obsession with melancholy was almost infinitely enriched by his boundless curiosity in the wider world – in everything from Christianity to astrology, astronomy, Latin poetry and Peruvian goldmines. Donne expressed it differently: love for a beloved, he writes in The Good-Morrow, especially as he wakes with her in the morning, “makes one little room … an everywhere”. And this is what I’ve learned: to cross Himalayan passes or do the tango or dream of Venice by all means, but also learn to do it in the intimacy of the “little room” where my heart is anchored, my “everywhere”. It’s almost impossible, but, in my experience, worth a shot.

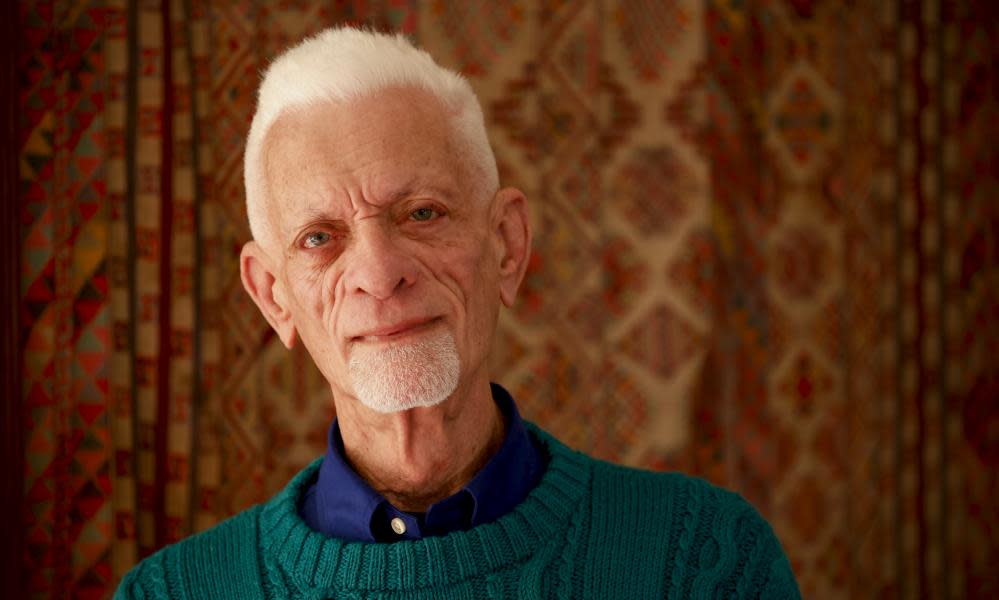

Robert Dessaix is the author of Night Letters, Twilight of Love, and The Time of Our Lives

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies