What happened to the promise to ‘defund’ America’s police forces – and to stop them killing Black people?

The news could barely have fallen at a more tragic moment.

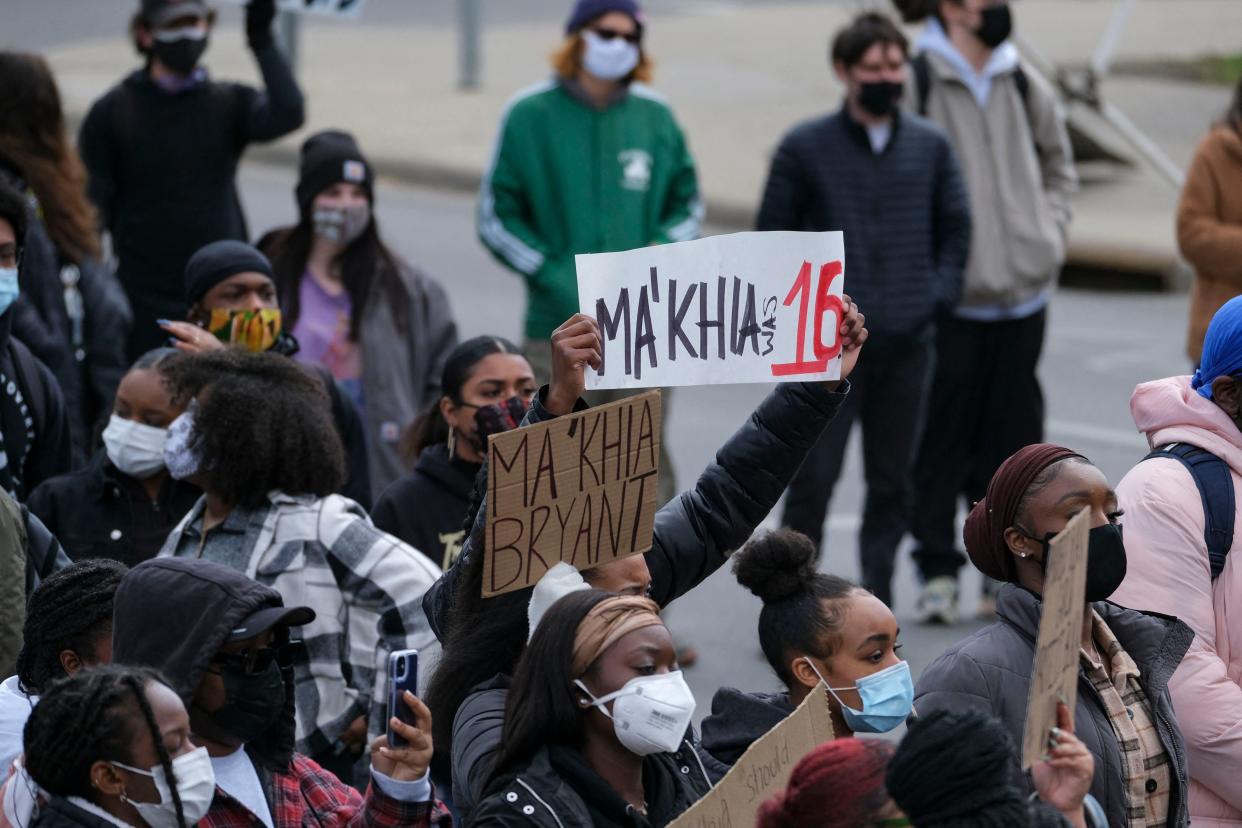

As jurors in Minneapolis were delivering a verdict in that most rare of cases, the prosecution of a white police officer for the killing of a Black man, reports emerged in Ohio, of something all too common – the shooting dead by police of a young Black woman. Her name was Ma’Khia Bryant, and she was just 16.

The circumstances of the killing of the teenager are being investigated. Initial reports said she was shot after running at two other girls with a knife. First reports are often wildly inaccurate in the favour of the police; the initial report issued about the death of George Floyd referred to a “medical incident”. Police in Columbus were quick to release body camera video of the shooting of Ma’Khia.

“She was a good kid, she was loving,” Hazel Bryant, who said she was the teenager’s aunt, said on a video posted on Twitter, according to Reuters. “She didn’t deserve to die like a dog on the street.”

The events in Ohio were a bleak reminder of a crisis confronting America – the repeated use of deadly force by police against people of colour, very often when those people are unarmed.

According to the Mapping Police Violence project, there have been 319 people killed by the police already in 2021, and there have only been three days when officers in one part of the nation or another did not have a fatal interaction with a member of the public.

In 2020, Black citizens accounted for 28 per cent of those of those killed by the police, despite only making up 13 per cent of the population.

The events in Ohio were on the minds of those people in George Floyd Square on Tuesday afternoon, who said while they welcomed the conviction of Chauvin, 45, for murder and manslaughter, he was just one officer, and the man whose image adorns the square, just one name among thousands of victims.

A 25-year-old woman, Christina SM, was among those marking the conviction at the intersection of two streets where Floyd lost his life. She was asked if there was any sense of relief, and whether people might sleep more easily. She dismissed the notion.

“Not if you’re a black man, or a young black man, or a 16-year-old girl,” she said. “Historically, we have seen this happen over and over again.”

She pointed out that 10 days ago, even as the trial of Chauvin was going on, another unarmed Black man, Daunte Wright, had been fatally shot during a traffic stop, 10 miles northwest of where everyone stood. The 20-year-old’s funeral is to be held this week.

SOMETHING OTHER THAN THIS

It was not not supposed to have been like this. A year ago, in the aftermath of Floyd’s murder, his face pushed into the road at the junction of East 38th Street and Chicago Avenue as Chauvin nonchalantly kneeled on his neck for more than eight minutes, the nation was jolted by a wave of protests for racial justice.

Taking place amid a pandemic that laid bare with hurricane force the racial and economic inequalities underpinning the nation, the protesters’ demands spread rapidly from charging and convicting the officers, to broader changes.

In several cities, there was a call for the scrapping of police forces as they were understood, and for them to be replaced by something more in tune to the public’s demands, and with community oversight. One of those places was Minneapolis.

The words spoken by Lisa Bender and other members of the Minneapolis City Council summed up the feelings of many across the country.

“We’re here because we hear you. We are here today because George Floyd was killed by the Minneapolis Police. We are here because here in Minneapolis and in cities across the United States it is clear that our existing system of policing and public safety is not keeping our communities,” she said. “Our efforts at incremental reform have failed. Period.”

The date was last June, and the location was Powderhorn Park, barely a mile from location of where Floyd had lost his life, and there was a belief in in the Twin Cities, and by people across the nation, that things had to change.

Key to this shift towards a more racially just society, nine of the city council’s 12 members said, was the need to get rid of the Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) as it was. Days before the rally, council member Jeremiah Ellison, who represents the city’s 5th ward and is the son of Keith Ellison, a Democratic Party power broker in Minnesota and beyond and currently the state’s attorney general, had tweeted: “We are going to dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department.”

He added: “And when we’re done, we’re not simply gonna glue it back together. We are going to dramatically rethink how we approach public safety and emergency response. It’s really past due.”

The words from Bender and others reverberated across a hot, anxious nation, stunned by the death of Floyd, so graphically captured on cell phone footage by a number of witnesses.

They were seized on by Donald Trump and his supporters, who were quick to play the race card, using the same coded language as Richard Nixon and others had, to stir up fears of crime and lawlessness in the suburbs.

“LAW & ORDER, NOT DEFUND AND ABOLISH THE POLICE. The Radical Left Democrats have gone Crazy,” the then-president tweeted.

Bender stood her ground. Speaking on CNN, she was asked whether she understood “that the word, dismantle, or police-free also makes some people nervous”.

“I hear that loud and clear from a lot of my neighbours,” Bender said. “And I know – and myself, too, and I know that that comes from a place of privilege. Because for those of us for whom the system is working, I think we need to step back and imagine what it would feel like to already live in that reality where calling the police may mean more harm is done.”

Yet almost 10 months on, the MDP has not been “defunded” or dismantled. More than 100 officers have left the force, anecdotal reports suggest police are less visible than they were, and that crime has spiked by more than 25 per cent. In the four neighbourhoods that rubbed up against each other at the intersection of East 38th Street and Chicago Avenue – Bancroft, Bryant, Central and Powderhorn Park – the jump is 66 per cent.

‘THERE’S NO MAGIC WAND’

Tracey Meares, a professor and the Founding Director of the Justice Collaboratory at Yale Law School, is often called upon to describe how to improve the nation’s police forces. She says it is important to accept you have to make better, and in some cases, simply less deadly, what is already there. There is “no clean” slate.

Furthermore there are as many as 18,000 individual law enforcement agencies within the country, with only partial federal oversight or even record keeping. Unlike in countries such as the United Kingdom there is no standardised training, no central register of “bad officers”.

As a result, the training of officers can swing from the elite members of the Secret Service, one of the country’s oldest federal police forces and tasked with protecting the president, to a sheriff’s officer in rural Oklahoma.

“I’m constantly thinking through approaches that will make the policing service that exists today, less harmful, because that's the thing we have today,” she said. “And there's no magic wand, that is going to get rid of it.”

And the police forces themselves are just part of a broader criminal justice system, that critics say is badly skewed in favour of the police, and against people of colour.

Chauvin was only the second serving officer, and the first white officer, in the history of Minnesota to be convicted of killing a member of the public.

And it is not just Minnesota. Phil Stinson, a criminologist at Bowling Green State University who tracks cases against police, has said that out of thousands of deadly police shootings in the US since 2005, fewer than 140 officers have been charged with murder or manslaughter. Only seven were convicted of murder

He told the Associated Press that historically juries have been more willing to give officers the benefit of the doubt that they acted reasonably during violent or fatal encounters. Mr Stinson said juries seem to also opt for lesser charges or acquit officers who have lost their job. “Officers’ criminal actions are not recognised as such by juries sometimes because everyone recognises that policing in this country is often violent,” he said.

The fight over the future of the police is happening across the nation. Joe Biden, who has backed reform but kept himself far away from the world “defund”, had originally planned to establish a commission to examine policing. The administration appears to have drawn away from that, and instead looks focused on helping pass the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act.

The measure seeks to overhaul “qualified immunity” policies, change the threshold for permitting use of force, prohibit police chokeholds at the federal level, ban no-knock warrants in federal drug cases, and create a national registry of police misconduct cases, but not defund police departments.

Last week, when Democratic congresswoman Rashida Tlaib called for the abolition of “policing, incarceration, and militarisation” after Wright’s killing, White House press secretary Jen Psaki said: “That’s not the president’s view.”

The House of Representatives passed a version of the George Floyd bill last month without any Republican support on a vote of 220 to 212. A similar bill was passed in 2020 but did not advance through a Republican-controlled Senate.

After the jury in Minneapolis this week delivered its verdict, Mr Biden said the push for racial justice could not “stop here”.

“No one should be above the law, and today’s verdict sends that message,” he said from the White House. “But it's not enough. It can't stop here. In order to deliver real change and reform, we can and we must do more to reduce the likelihood that tragedies like this will ever happen again.”

There is also movement at a local level. The New York Times said 16 states have restricted the use of so-called neck restraints, such as the one used by Chauvin when he killed George Floyd.

A further 21 additional cities have called on officers to intervene when they think another officer is using excessive force.

We are going to dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department.

And when we’re done, we’re not simply gonna glue it back together.

We are going to dramatically rethink how we approach public safety and emergency response.

It’s really past due. https://t.co/7WIxUL6W79— Jeremiah Ellison (@jeremiah4north) June 4, 2020

MINNEAPOLIS’ FIRST BLACK POLICE CHIEF

In Minneapolis, political disagreements, primarily between the city council members on one hand, and mayor Jacob Frey and police chief Medaria Arradondo on the other, have help create a situation that has left many residents confused. Critics say issues have been stymied too, by the existence of the unelected Minneapolis Charter Commission, whose members are appointed by the Chief District Court Judge, and have the power to block the council’s actions on certain issues, in particular the number of officers on the force.

Some in the city have far more ambitious ideas, and would like to have civilian control of the police, an idea borrowed from the Black Panther Party in the 1970s.

“Right now, the system is not working for us,” says Angel Smith-El, a member of Twin Cities Coalition for Justice 4 Jamar (TCC4J), a community group working against police brutality and misconduct, formed after the 2015 police shooting of Jamar Clark.

“Having community control we could respond more quickly. Right now, people are tired, stressed and freaked about about Covid. The definition of insanity is when you keep doing the same thing, and nothing changes.”

In the 11 months since Floyd’s death, Mr Arradondo, appointed police chief in 2017 and who once had to sue the force for racial discrimination as he worked his way up through the ranks, has tried to push through some changes.

A star witness in the trial of Chauvin, one of four officers he fired after Floyd’s death, he has banned the use of police chokeholds and neck restraints, demanded officers seeing a colleague using improper force to step in, and blocked those officers involved in using deadly force from reviewing body camera footage before completing their initial report.

The chief and the mayor have pushed back at efforts by the city council to reduce the number of mandated officers, managing to keep the cap at 888. In December, the council and the mayor agreed to shift $8m from Frey’s $179m policing budget to mental health teams and violence prevention programmes.

Last year, Mr Frey was booed at a public meeting after refusing to commit to wholesale plans to abolish the force.

Council member Steve Fletcher said he believed that both the mayor and the police chief had acted as a block to pushing through more progressive measures.

Mr Frey refused repeated requests from The Independent for an interview and an MPD spokesperson said the chief was too busy to speak given the demands on his time overseeing security during the Chauvin trial.

Earlier this month, the mayor, who appoints the police chief, who is then approved by the city council, told National Public Radio: “I do not think that we should be dramatically defunding and abolishing the department. And some council members and certainly my opponents for mayor believe that.”

The situation in Minneapolis has made many residents fearful and anxious.

On a recent morning outside the Cub Supermarket in southeast Minneapolis, close to the remains of the MDP’s third precinct building, which was set on fire by demonstrators last year, many residents, a number of them Black, dismissed notions of “defunding” the police.

Indeed, there was a general agreement on the necessity of the force. “We need the police, but we need good officers not bad officers,” said one shopper, Caroline Longs.

Another, Albert Rein, said since the killing of George Floyd “you seldom see the police”. He added: “People are always jumping red lights, and the are more carjackings.”

Steven Belton is president of the Twin Cities branch of the National Urban League, a civil rights movement that dates back to 1910.

He opposes plans to defund the police, but believes forces across the nation are ready for reform. He said he would have liked to see the MPD “unpacked”, or decentralised, with other agencies handling issues such as people with mental health problems.

He said better training, mandates that demanded forces reflected the communities they served, and a national register of officers to allow their records to be checked, were the “low hanging fruit” that could be done easily and quickly to improve matters. He also supported a civilian police commissioner, to whom a police chief reported, to increase civilian oversight.

“It's not going to happen organically, you still need to do training, you still need to have leadership from the top down, to press for diversity and equity and fairness and justice for all,” he said.

“These are not foreign concepts to American democracy. But they're foreign in terms of their actual realisation and execution.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies