‘Half an American dream’: DACA was meant to be temporary. 10 years later, immigrants want relief.

One woman fears being returned to the Middle East after living most of her life in Florida. A North Carolina man moved to Mexico rather than live under the constant threat of deportation. One woman needs a lifesaving kidney transplant but cannot qualify for one without a green card.

Beneficiaries of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, are protected from deportation and given permission to legally work in the United States. The policy serves immigrants who were brought here as children.

But the program, which turns 10 on Monday, has been under steady attack – from former President Donald Trump, a barrage of lawsuits and state and federal lawmakers who argue it is illegal to allow some immigrants to stay here without an act of Congress. A federal appeals court in New Orleans is expected to rule on the policy this year.

"A policy that allows anyone who arrives as a minor to stay here is a terrible policy," said Jessica Vaughan, director of policy studies at the nonprofit Center for Immigration Studies, which promotes stricter controls on immigration. "It incentivizes sending kids illegally here with smugglers, puts them in danger and undermines our legal immigration system."

President Barack Obama introduced DACA in 2012 as a temporary relief until Congress passed more permanent solutions. It never did, and today recipients cling to the tenuous policy as a portal to opportunity.

DACA recipients – who have grown into adults in the decade since the program was introduced – number more than 600,000 today. They must reapply for status every two years. They are activists, college students, journalists, entrepreneurs, nurses and teachers. The DACA-eligible population earned $23.4 billion in 2017, up from almost $19.9 billion in 2015, according to a recent report. More than 93% of DACA-eligible individuals were actively employed in 2017.

With Congress locked on the issue, DACA has been the most sweeping immigration reform since Ronald Reagan's 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act granted amnesty to nearly 3 million undocumented immigrants.

DACA "really was an experiment to see what would be the impact to give them temporary legal protection and authorization to work," said Julia Gelatt of the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan, Washington-based think tank. "These protections have greatly benefited not just DACA holders but the country overall."

The USA TODAY Network interviewed DACA recipients to better understand how the program changed their lives. These are their stories.

– Rick Jervis, USA TODAY

She needs a green card to get a kidney transplant

By Rick Jervis, USA TODAY

At 12 years old, Erendira Mendez found herself lost in the desert.

Mendez, along with her mother, brother and uncle, had been dropped off at the U.S.-Mexico border near Arizona by a smuggler and told to walk north. Empty desert stretched to each horizon.

Her mom could barely walk. The family was out of water. They thought of returning to Mexico, but going south looked just as hot and bleak. They kept walking.

A few weeks earlier, the family learned that Mendez’s father, who was working in North Carolina, had an accident at work and needed his foot amputated. In a panic, Mendez’s mother gathered the family and headed north to the United States.

After three days of trekking through the desert, another smuggler picked them up, held them hostage for a week until family members wired a ransom, then released them.

“It was awful,” said Mendez, now 34 and living in North Carolina. “I’m still traumatized.”

Despite her harrowing entry to the United States, Mendez thrived at school in Greensboro, North Carolina, where the family settled. Teachers constantly misspelled or mispronounced her name. One teacher asked to see her green card, embarrassing her in front of classmates. Neighborhood kids called her a “wetback.” Still, she kept her grades up.

Mendez graduated high school and received DACA in 2012, when she was 23 with a 4-year-old daughter. Today, she is a program manager at the Hispanic Federation, an advocacy group, helping other undocumented young people come out of the shadows.

The need for more permanent status in the United States has taken on a life-or-death urgency. Diagnosed with stage 4 chronic kidney disease, Mendez requires a new kidney but was told she needs private insurance or a green card to get on the transplant list.

“You stand there in the hospital and wonder, ‘What’s going to happen with my life?’” she said. “I’m exhausted and tired. What I need is a decision. What I need is permanent relief. I’ve paid my dues.”

She wants to visit her grandmother in her homeland

By Bill Keveney, USA TODAY

Eva Santos Veloz can’t travel to the Dominican Republic, her native land. So she settles for a taste of it.

Every year, her grandmother travels from the island to her home in the Bronx, New York, to bring her pan de agua, mangoes and other delicacies from the Caribbean nation.

“She brings me chips, cheese, soda, candy. She brings a whole supermarket from the Dominican Republic so I can try all the things,” said Santos Veloz, 32, who can’t leave the United States for an ordinary family visit under DACA. She hasn’t been back to the land of her birth since moving to the United States when she was 9.

Soon, she will have to find a new connection to her roots. Her grandmother, now 93, said she’s no longer able to make the trip to the United States and this will be her last visit.

Santos Veloz, the mother of three U.S. citizens and an organizer for United We Dream, an immigrant youth-led network, considers herself both American and Dominican.

“I’m American because this is the only home that I know,” she said.

She appreciates the opportunities she’s had in the United States and with DACA, which she received approval for in 2013. DACA allowed Santos Veloz, who was paid in cash for low-wage work, to get a better-paying job at a bank, find an apartment and move out of a shelter.

But she’d like to be able to visit the Dominican Republic and her many relatives who live there, including her grandmother. She wants to take her children there.

Santos Velez isn’t sure if she’ll ever be able to return to her homeland. In the meantime, she has the memory of the last bag of pan de agua her abuela brought her.

“It tasted super amazing. I had the whole bag. I think I gained like 10 pounds,” she said, laughing.

She wants DACA critics to see her humanity

By Rafael Carranza, Arizona Republic

Maria Valeria Garcia woke up at 4:30 a.m. She walked from her hotel to the courtroom for the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans.

Garcia, 19, had flown from Phoenix the day before with Aliento, a community organization that works with mixed-status families in Arizona where she had been interning.

It was July 6. Three judges from the Fifth Circuit would hear oral arguments to determine the future of DACA.

DACA has been in place for more than a decade. Her older brother had received DACA, but her application stalled in 2021 after a federal judge in Texas ruled the program unlawful.

The case now stood before these judges, and Garcia wanted to be inside the courtroom.

Security guards began handing out numbers to allow people inside. Hers was 17. She’d have a seat.

The hearing lasted about 40 minutes. Everyone around Garcia was busy scribbling notes, including her.

She hoped the judges would look at her.

“I honestly thought that my presence and other people that were in the courtroom would kind of, somehow make the judges look at us or see us as humans,” she said.

After it ended, Garcia filed out. Any hope she fostered about having her DACA application approved seemed to slip further away.

“If DACA ends,” she said, “it's kind of like, what am I hoping for?”

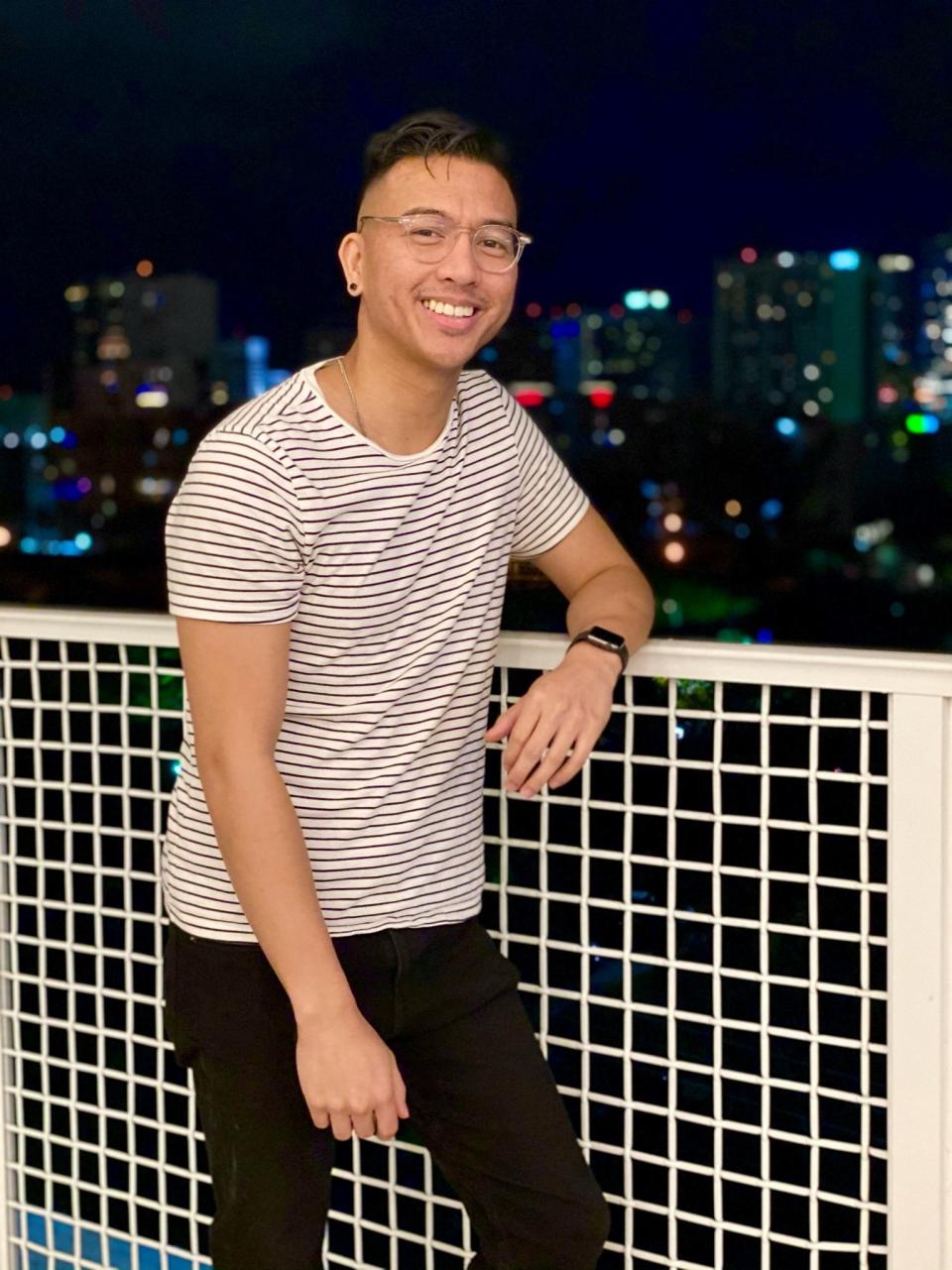

DACA helped ease his depression

By Rick Jervis, USA TODAY

William Avilez withered away on a friend’s couch, depression keeping him from doing much besides getting up and showering each day. He was undocumented, with minimal college and job prospects, and had been kicked out of his home by his stepfather for being openly gay.

It was supposed to be one of the most exciting times in his life: Freshly graduated from high school with honors and a 3.7-grade point average. Dreams and ambitions bubbling in him. But instead of thumbing through college acceptance letters, Avilez was working low-paying construction jobs and washing dishes at a restaurant. He was the son of Nicaraguan immigrants, brought to the United States when he was 5.

One day, his mother called: He had received a letter notifying him he had been approved for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. His future opened up again. Avilez cried on the couch.

“It was such a huge relief,” said Avilez, now 28. “Soon my Social Security card would arrive, soon I’ll have my driver’s license. I could start working and figuring out my future.”

Avilez is now a lead research coordinator in the infectious disease division at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta and is pursuing a master’s degree in health administration – opportunities spawned by DACA.

His past – fleeing Nicaragua by boat, his mother hiring a "coyote," or human smuggler, to bring them to the United States from Mexico, his friend’s couch – has faded into memory.

He wants to become a pilot. He can’t with DACA.

By Rebecca Morin, USA TODAY

Ronnie James' first words were “Air Jamaica.” He was always obsessed with airplanes.

At one of his family's homes in St. Lucia in the eastern Caribbean, planes would fly overhead on their way to the airport. When he was 9, he flew on a plane for the first time, traveling to a new life in North Carolina.

For years, all James could think of was becoming a pilot. After all, it was a pilot who had brought James to the United States, where he was able to see his mother for the first time in two years.

But James, 24, isn’t allowed to take the tests to become a pilot. He wishes he could obtain a green card or citizenship so he could make “my dreams happen without having one hand tied behind my back.”

When James was in sixth grade, his family moved from North Carolina to New York City for more opportunities. There, James attended an aviation high school where he studied to become an aviation mechanic – a concession James thought would get him closer to his dream. But that job, too, was unavailable to him because of his immigration status.

A family friend alerted James and his mom to the DACA program in the summer of 2012. By December, James was able to pick up a work permit and Social Security card.

James, who graduated from City College of New York and is now in graduate school there, said DACA “has not been enough and was never enough.”

“Beyond your economic ability to pay taxes and having a job, you don't really get any other benefits with your DACA status.”

Living in the US as kids without parents

By Rick Jervis, USA TODAY

Gabriella Fernandez kissed her parents as they left for what was supposed to be a brief visit to their homeland of Venezuela. Instead, her parents – who had relocated to Florida two years earlier – were denied reentry into the United States when they tried to come home to their children.

The Fernandez sisters – Gabriella, Valeria and Raquel, then 11, 13 and 18, respectively – were on their own in Florida.

“We were starting from zero,” Gabriella Fernandez said. “We had to learn how to cook and clean. It was a big learning curve.”

Fernandez was 9 in 2007 when Venezuela’s political instability forced her family to move from Maracaibo to Orlando, where they opened a jewelry store. Two years later, the parents were stuck in Venezuela after they had overstayed their U.S. tourist visas.

Raquel Fernandez, then 18, took custody of her younger siblings. She drove them to school on her way to college classes. The girls divvied up household chores and learned to cook and clean. Her parents sent them money, but the daughters lost their house to foreclosure and downsized to an apartment.

At school, Gabriella Fernandez racked up honors and college credits. When she turned 15, she received DACA.

Armed with a Social Security number and shielded from deportation, she graduated high school and earned a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Central Florida, graduating magna cum laude. In 2018, she was reunited with her parents in Florida.

Gabriella Fernandez, now 23, recently received a full scholarship to New York University’s Long Island School of Medicine, inching closer to her dream of becoming a doctor.

“That goal only exists because DACA exists,” she said.

He moved to Mexico to avoid a life of DACA limbo

By Rick Jervis, USA TODAY

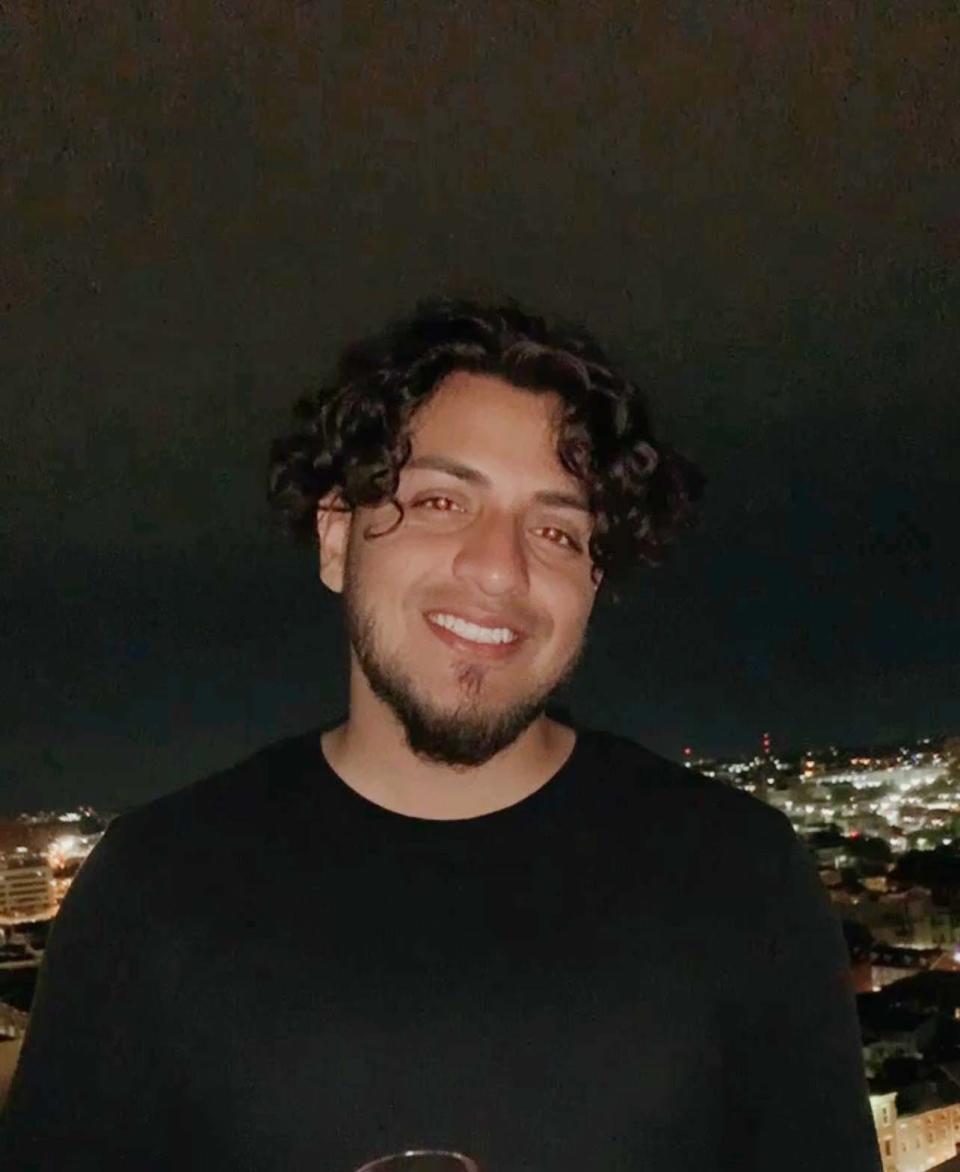

Life was going pretty well for Mauricio Lopez.

Lopez, the son of Mexican immigrants who was brought to the United States when he was 5, had obtained DACA, graduated high school with honors, worked in sales, then started a business buying and selling cars. He liked supporting his mother financially and keeping food on the table.

But even with DACA, there were limits. He couldn’t take out a loan to grow his business, and he couldn’t travel abroad. The threat of deportation loomed. A constant reminder was his older brother, Silverio, who was deported years earlier after a traffic violation.

“I was given only half an American dream,” said Lopez, 28. “It was like a free trial.”

When Trump won the White House in 2016 and threatened to dissolve DACA, Lopez made a radical decision: He would self-deport back to Mexico. He and his mother bought a one-way bus ticket from Durham, North Carolina, to Mexico City to stay with an uncle. Their American dream vanished behind them.

It was strange returning to Mexico, Lopez said. But as they crossed the border, he felt “like an eagle let out of his cage.”

Today, in Mexico City, Lopez teaches English and runs Dream Teach, an initiative to help other DACA recipients who have returned to Mexico land good jobs there.

Though he misses some things in the United States, like his favorite Indian restaurant, Lopez said DACA was too fickle to live with.

“There’s no end game with DACA,” he said. “There has to be a pathway to citizenship.”

He is his parents’ retirement plan

By Daniel Gonzalez, Arizona Republic

April 30, 2003, started with Juventino Meza waking up before dawn in Atoyac, a small town in the Mexican state of Jalisco. It ended with Meza sleeping in a safe house somewhere near Los Angeles.

In between, Meza flew to Mexicali with his older sister, Mari, and younger brother, Jose. They were on their way to reunite with their parents already living and working low-wage jobs in St. Paul, Minnesota.

In Mexicali, coyotes, or smugglers, drove the three siblings to the border. Meza’s sister nearly drowned while swimming across a canal.

“Go ahead, leave me,” Meza recalls her yelling as she struggled in the water.

The siblings finally made it to Minnesota and blended into life there. By the time President Barack Obama announced DACA in 2012, Meza had graduated with a degree in justice and peace studies from Augsburg University in Minneapolis.

He was approved for DACA in November 2012. The first thing Meza did was get his driver’s license so he didn’t have to worry about getting pulled over and deported. Having a driver’s license made him feel “a little normal.”

He later bought a two-story, 2,300-square-foot house with gray siding. Meza used an FHA loan he wouldn’t have qualified for without DACA.

After Trump was elected president, Meza felt defeated. He sold his house and moved to San Francisco, where he worked for an immigration lawyer.

Meza returned to Minnesota in December. He now works as a health care compliance and contracts specialist earning more than $90,000 a year. He’s also a part-time student at Mitchell Hamline Law School in St. Paul.

Meza’s father still works in construction. His mother cleans houses. In March, Meza bought a house for them in West St. Paul, mainly as a way to say thank you. Meza lives in the basement.

“They are never going to have a retirement,” Meza said. “I see myself as sort of their retirement plan.”

She’s no longer afraid to travel within the US

By Rebecca Morin, USA TODAY

Silvia Medina-Balcazar spent months planning a trip to Puerto Rico for her 29th birthday in June.

But the week before her trip, her stomach dropped. It was the first time Medina-Balcazar would be leaving the mainland United States in more than 20 years.

“‘Oh my God, are they going to let me back in?’” Medina-Balcazar thought to herself. “I've built a life that I like and do I really want to risk that? But I'm a risk taker.”

Medina-Balcazar ended up having a blast. For the first time in her life, she felt similar to her home country of Bolivia. The signs were in Spanish, the people around her spoke Spanish, and the colonial-style homes reminded Medina-Balcazar of her childhood.

During the flight home, Medina-Balcazar’s anxiety spiked again. She feared she wouldn’t make it past the TSA.

“The biggest feeling of relief came through my body,” she said after passing through security. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, OK, this trip was actually pretty fun.’”

Medina-Balcazar moved to Alexandria, Virginia, from Santa Cruz Department in Bolivia when she was 9. She applied for DACA after high school.

DACA changed her life, Medina-Balcazar said. She got a driver’s license. She was able to apply for a scholarship to Trinity Washington University in Washington, D.C. Now, with a job as a supervisor for a molecular biology department, Medina-Balcazar feels stable enough to do something she has always wanted to do: travel.

In the past several months, Medina-Balcazar has visited Seattle and Los Angeles.

“I realize, 'You know what, why not?'” she said. “I've been trying to see the U.S. as much as I possibly can.”

He feared running into the police

By Daniel Gonzalez, Arizona Republic

Emmanuel Gonzalez Perez was walking home when a police car pulled up and blocked his path.

Gonzalez, then 17, had just finished a dishwashing shift at a Mexican restaurant. He was still dressed in his work attire, black pants and a white shirt. He was in a predominantly white area in Tustin, California, on his way home to neighboring Santa Ana.

Gonzalez wasn’t carrying ID because he was undocumented. His mother brought him to the United States from Guadalajara, Mexico, when he was 7.

Are you in a gang? the officer asked. Do you have a parole officer?

Gonzalez felt as if he were being racially profiled.

The officer told Gonzalez to sit on the curb while he called his supervisor. Gonzalez remembers his hands shaking.

Gonzalez was certain he was going to be turned over to immigration authorities. To his surprise, the supervisor told the officer to let him go.

For years, Gonzalez tried to avoid encounters with law enforcement. He made sure not to drive through towns with Border Patrol checkpoints.

It took Gonzalez several years working minimum wage, paid-under-the-table jobs to save up the nearly $600 in fees for DACA. He was approved in 2016 when he was 20.

With his work permit, Gonzalez got a full-time job as a community liaison at a public high school in Stockton. He plans to finish his bachelor’s degree in psychology this fall at Cal State University, Stanislaus. His goal is to become a school counselor.

In June, Gonzalez, now 26, renewed his DACA status for two more years. He worries less about being stopped by the police and deported. In July, he even flew to Hawaii for a vacation.

‘That was the start of my future’

Rick Jervis, USA TODAY

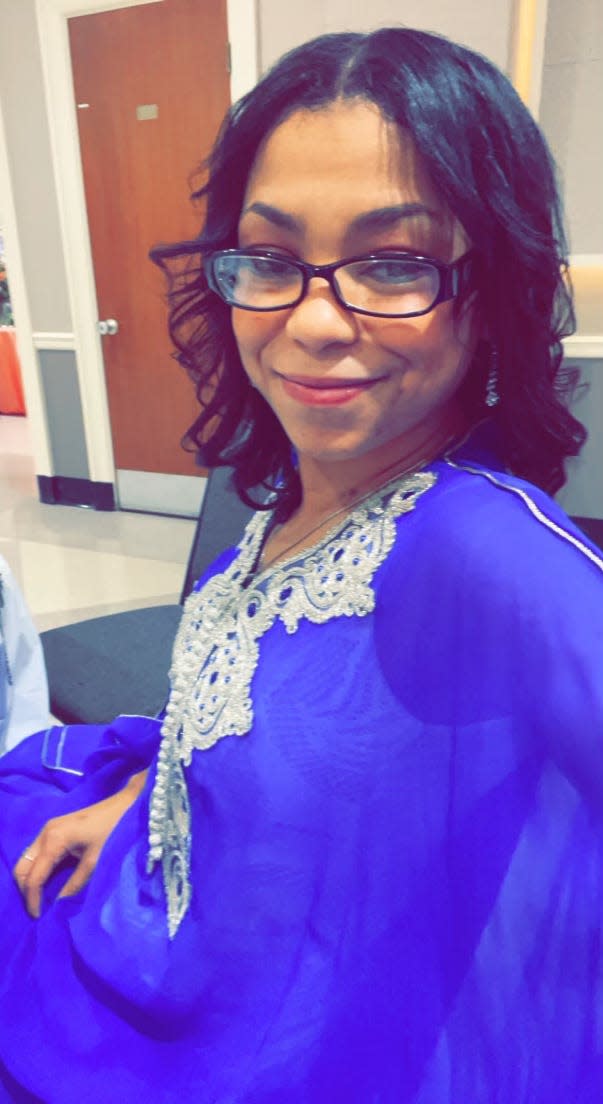

Faten Hamadna saw the hours and effort her father poured into the Stop & Shop where he worked. Getting in early, coming home late, bone-tired.

She was proud of how hard he worked to keep food on their table. But was this the life for her? As an undocumented high school student, her options were limited. Helping her father at the store seemed the most likely path

“I thought, ‘I’m going to be like this for the rest of my life,’” Hamadna said. “It was challenging.”

Brought to Florida from the Palestinian territories when she was 4, Hamadna grew up American, picked up English quickly and blended in with her friends. She marveled as her friends took trips to Syria or Latin America or got driver’s licenses – all unobtainable for her as an undocumented student.

Her goal was to be the first member of her immediate family to go to college. But that ambition seemed painfully out of reach, because her family couldn’t afford out-of-state tuition and she couldn’t land a decent-paying job without a work permit. School seemed pointless. Her grades slipped.

Then a Guatemalan friend told Hamadna about DACA. Her father gathered the money for a lawyer to help with the paperwork.

When she received her acceptance letter, Hamadna, tears welling in her eyes, texted her dad: “I think it’s going to work,” along with a picture of the letter.

“That was the start of my future.”

Thanks to a scholarship through TheDream.US, which helps undocumented young people, Hamadna, now 22, will graduate with an associate’s degree from Broward College in the fall. She speaks four languages – English, Arabic, Spanish and Portuguese – and plans to transfer to a four-year university to study communications.

“Without DACA, I wouldn’t be where I’m at today.”

He gave up his dream of playing soccer

By Rebecca Morrin, USA TODAY

As a high school student, Jose Covarrubias was offered the opportunity of a lifetime: travel to Italy for a soccer trial. It could have gotten him one step closer to his childhood dream of playing soccer for Chelsea Football Club in London.

But Covarrubias couldn’t go. He was undocumented, and if he left the United States he wouldn’t be allowed to return home to his mother, his friends or his high school.

“It was devastating,” said Covarrubias, now 25, who lives in Baltimore. “That was a pretty difficult time.”

Covarrubias was born in Tamaulipas, Mexico, and came to the United States when he was about 2 years old. He didn’t know that he was undocumented until he got to high school.

His mother filled out his first DACA application. Covarrubias didn’t realize the limitations he would still face. He wanted to be the first in his family to go to college, but didn’t know that DACA recipients couldn’t receive federal financial aid. Without the money, he couldn't go.

Covarrubias built a life he loves. He coaches young soccer players. He has a daughter. He feels he has gotten the opportunities that other immigrants might not have.

Still, he worries his life could be upended at any moment.

“It’s super-terrifying,” he said. “A lot of people here, they have a family already, they've established a livelihood and the possibility of just getting picked up at any moment. … That is something that people that have DACA are scared about.”

Dreaming of a life without fear

By Danae King, The Columbus Dispatch

Sara Hamdi remembers seagulls swooping through blue sky and baby crabs scuttling along the sand. As an undocumented immigrant, that day at the beach was a rare moment of bliss.

Hamdi, 32, has experienced only brief pockets of relief since she received DACA 10 years ago.

That day two years ago, she walked the beaches of Cape Cod with her niece, nephew and brother. At each one, her niece and nephew plucked shells from the sand and put them in plastic beach pails to take home to Ohio.

She often pulls up a photo of that day on her phone. In the photo, Hamdi is squinting in the sun, smiling over her shoulder at the camera beside her family as seawater tickles their feet.

Hamdi was born in Casablanca, Morocco, and brought to the United States by her parents when she was 5. They overstayed a tourist visa.

She lives in Clayton, Ohio, about 20 miles northwest of Dayton, where she is a sales representative for T-Mobile.

Hamdi feels nervous every day about her immigration status. Little things trigger her anxiety, like when a police officer pulls up behind her while she's driving, and her whole body tightens. She longs to go about her days without worrying about being deported.

"I try to stay hopeful," Hamdi said. "Every day I wake up, I see it as another day to keep going."

She wishes every day was like that day at the beach.

She cannot travel to her homeland

By Rebecca Morin, USA TODAY

It was a dream come true for her parents.

Min Hee Cho, 25, a network planning analyst, was able to help them buy a townhome in the suburbs of Chicago through an aid program for DACA recipients. Out back was a sprawling field where they could play with their puppy.

Cho’s own dream is a little more out of reach. She longs to visit South Korea, to see relatives she has not seen in decades and to have a giant family reunion.

“It's very wishful thinking,” said Cho, who is a DACA recipient.

Cho, who lives in Chicago, learned she was undocumented in seventh grade, as her older sister was heading into high school. Their parents warned them that they needed to excel in school and get scholarships to college because they wouldn’t be eligible for financial aid.

For Cho, the family’s status was hard to understand. She had been in the United States since she was 4 after her family immigrated in 2001.

“It was definitely a lot to grasp at the moment for like a seventh grader, or eighth grader, to think that their futures are kind of in an uncertain limbo state,” Cho said.

Cho attended Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, where she was able to get financial aid. She graduated in 2019.

After the 2020 election, Cho began speaking out. She wants Congress to create a pathway for DACA recipients and other undocumented immigrants.

“It's been very difficult to know that people are politicizing my existence.”

He hated working in a restaurant as an undocumented immigrant

By Rick Jervis, USA TODAY

Mike Jonathan was on the commuter train from Chicago to Des Plaines, the bleakness of his life weighing on him. Ahead lay another 11-hour shift at a Chinese restaurant for tips, followed by sharing a room in a cramped two-bedroom apartment with five other undocumented workers. The restaurant's owner would regularly berate him and the other workers.

His future didn’t seem much better. Jonathan arrived in the Chicago area from Jakarta, Indonesia, in 2001 as a 10-year-old boy with his mother and brother shortly after his father died. They moved in with an aunt in southern Cook County while his mother returned to Indonesia.

Jonathan graduated high school with decent grades. He had a restless interest in computers, but without documentation, he couldn’t afford college.

In late 2014, he found an immigration clinic covering the costs of applying to DACA. He applied and pushed it out of his mind. He kept working at the restaurant.

As the train rumbled north toward Des Plaines that day, Jonathan pulled out his smartphone to check the status of his DACA application. “APPROVED,” it read, next to a green checkmark. He rubbed his eyes and looked around the train.

“I literally thought it was a dream,” he remembered. “I had to pinch myself."

DACA allowed him to quit the Chinese restaurant and move to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where he attended Broward College, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in data analytics.

This month, Jonathan, now 31, returned to Chicago to move in with his brother, a sushi chef, and find a good-paying job. He hopes to work for a company that serves marginalized communities.

“My dream goal is to give back to the communities that have always guided me in life,” he said.

‘I always knew it could be taken away’

By Bill Keveney, USA TODAY

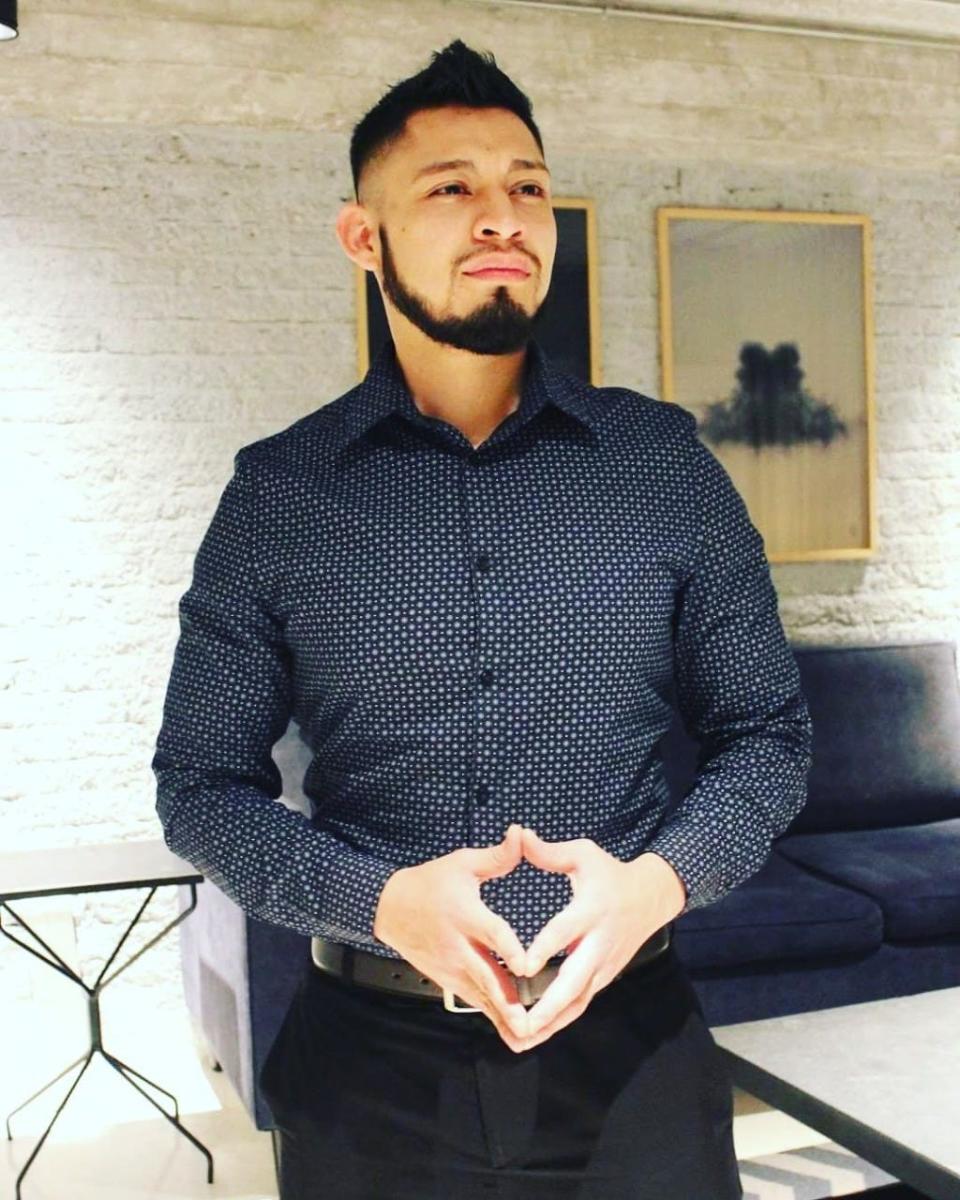

For Cesar Rodriguez, DACA was “the missing piece” to his life in the United States.

Rodriguez, 28, owns two homes in Nashville and works as a mechanical engineer for international conglomerate Philips. But his worries about his status in his adopted homeland have never disappeared.

“In the back of my mind, I always knew it could be taken away,” he said.

Rodriguez said he, his brother and their parents, who came to the United States from Mexico, all happily pay taxes to support government programs for which they aren’t eligible as undocumented immigrants.

Even if DACA is declared illegal, Rodriguez said he isn’t giving up on making it in the United States. He said it’s time for undocumented immigrants to join together to rally for a permanent solution, making it clear that hardworking families like his are the best advertisement for a path to citizenship.

“You have a lot of people here who continue their education, join the workforce and become very productive members of their communities,” he said. “I feel like a lot of us have the same sentiment. We’re here. This is all we know. And to just make us leave like that – that’s what they're trying to do – one would argue that's pretty unfair."

He gave out T-shirts that said: ‘Obama deports Dreamers’

By Daniel Gonzalez, Arizona Republic

Juan Gallegos attended college thanks to private scholarships and a Nebraska law requiring state schools to offer in-state tuition to undocumented immigrants. But he couldn’t use his education because he didn’t have a Social Security number.

After leaving the University of Nebraska, he worked as a roofer in 100-degree heat, frustrated that his four years of college were being wasted. He worked other under-the-table jobs. Some employers paid him less than minimum wage.

Originally from Cuauhtémoc in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, Gallegos came to the United States in 2001 when he was 12. His family entered with tourist visas and settled in Hastings, Nebraska, where his father worked at a feed lot.

Gallegos, 33, now lives in Denver. He runs a marketing consulting business, called FactorX. He said the business is profitable after only two years.

Gallegos began sharing his story anonymously, writing in support of the Nebraska Dream Act, the 2006 law giving in-state tuition benefits to undocumented "Dreamers." He began sharing his story publicly after DACA was announced in 2012 because he felt more secure.

He used graphic design skills he learned in college to design the slogan, “Obama deports Dreamers” printed on T-shirts and buttons for other immigration activists.

On June 15, 2012, Gallegos took part in a demonstration outside an ICE detention facility in Los Angeles to protest the deportation of undocumented young people. He wore his black graduation cap from the University of Nebraska.

Hours later, Gallegos gathered with other Dreamers at the University of California, Los Angeles’ Labor Center to watch President Barack Obama announce DACA. Gallegos was certain the years of work by "Dreamers" leading up to the announcement had pressured Obama to create DACA.

‘I hate the constant living in limbo’

By Bill Keveney, USA TODAY

DACA helped Rita Castañon feel like her high school classmates in her hometown of Morristown, Tennessee: she was able to get a job and a driver’s license.

But when she applied for college, the limitations of DACA were made clear. She wasn’t eligible for Tennessee Promise, a state program that offers a tuition-free community college education, and she lives in a state where DACA recipients pay out-of-state tuition at state colleges, multiple times the in-state fee.

Castañon, 24, came to the United States from Mexico when she was 6. She hopes to become a lawyer and help immigrants and others in Appalachia, a region that typically doesn’t offer the level of support services found in larger cities home to many immigrant residents.

But it’s hard to plan for law school and a career with DACA’s two-year renewal requirements, no path to citizenship and the possibility the program could be erased.

"I don’t like the question a lot of people ask me: ‘Where do you see yourself in five years?'" she said. "I hate the constant living in limbo."

Still, Castañon knows she is luckier than many other immigrants. A 2018 federal raid on a nearby meatpacking plant, which left dozens of undocumented workers subject to deportation, helped her see how fortunate she was.

“It was very traumatic. That’s when I felt relieved to have the work permit, because it was a reality check of how horrible the system can be. Mothers were torn apart from their children. Mothers and fathers were working there, so there were instances where the children were left alone,” she recalled.

She was heartened by the response from all segments of her rural Appalachian community, including Hola Lakeway, a nonprofit organization where she now works part-time as an outreach director.

“It united the whole community,” she said.

She finally got her driver’s license

By Rafael Carranza, Arizona Republic

Tessa Hong Flight felt useless when she couldn’t obtain her driver’s license along with her friends in high school.

“I couldn't go to school, can't work legally, can't even drive around,” she said.

Hong Flight had grown up knowing she was undocumented. Her mother brought her to the United States from China in 2003 when she was 11. Her mother went back before legalizing her status, but Hong Flight stayed with a family that took her in.

She had sought legal status, but after her application for residency was denied, her attorney told her about a new program called DACA. She immediately applied.

In a matter of weeks, she received her permit. And one of the first things she did was ask her boyfriend to take her to take a driver’s license test.

Hong Flight couldn’t parallel park very well and failed.

She went home, practiced a bit. The next day she took the test again and passed.

Hong Flight, 30, now drives around Houston as a real estate agent. It hasn’t been the only change DACA brought to her life. She got married three years ago, and having DACA allowed her to get conditional permanent residency after her marriage.

“It is the American dream to really come from nothing and not have the resources and opportunities like everybody else,” Hong Flight said. “But really making something of yourself and your circumstances, and taking what you're given and just run with it. And that's what I have done.”

DACA is a privilege others in her family do not have

By Bill Keveney, USA TODAY

Britany Gonzalez still remembers her mother’s fear.

One day, as the woman drove to her 5 a.m. warehouse shift in Memphis, Tennessee, police were randomly stopping cars to check license and registration, documents she didn’t have. Gonzalez’s mother didn’t get stopped, but another undocumented woman was less fortunate. She was detained for a few days.

“That really stuck with me. She said it was a very stressful, very scary situation,” said Gonzalez, a Memphis resident who this month begins her senior year at Lipscomb University in Nashville. “I was very young when that happened and I remember thinking, ‘When I get older, how am I going to be able to drive or obtain all these documents that I need?’ ”

DACA partially resolved that issue, allowing Gonzalez the opportunity to get a driver’s license, a social security number and a work permit.

She wishes there were a more permanent solution that would provide a path to citizenship, but she appreciates how the federally recognized status helped her escape some of the hazards her mother and others have faced. Gonzalez, 21, came to the United States from Mexico at the age of 4 in 2006.

“It’s a big thing … to have those documents and feel safe, to know that you’re doing everything that you can to be in this country legally. It’s a privilege because so many people – so many of my close family – don’t have that opportunity,” said Gonzalez, who works at her uncle’s taco restaurant outside of Memphis and for the Tennessee Immigrant & Refugee Rights Coalition. “Just to freely move around in this country (is) one of the biggest things.”

Risking it all for higher education

By Daniel Gonzalez, Arizona Republic

Angelica Guzman was having lunch in the student union when news broke on the TV.

President Barack Obama was announcing new actions “to mend our nation’s immigration policy to make it more fair” for young immigrants.

It was June 2012. Guzman was a political science major at the University of Utah.

Originally from Puebla, Mexico, Guzman had been living in the United States without legal status since her mother brought her to the country when she was 9.

Obama’s DACA announcement brought tears to her eyes. It meant she could legally work and financially help her parents. Her mom and dad each worked multiple jobs: cooking, cleaning, taking care of other people's children, delivering newspapers.

As a DACA holder, Guzman was able to apply for “advance parole” – permission to temporarily leave and return to the United States. She studied in Germany for a semester. Lawyers strongly advised Guzman against leaving the United States. They warned she might not be allowed back in.

Returning from Germany, Guzman had a scare. A U.S. customs officer at the airport in Philadelphia didn’t recognize the documents Guzman presented. The officer sent Guzman to a room for secondary inspection. Guzman waited for an hour and a half, saying prayers. Another officer finally arrived with her passport, “threw it at me” and said she could leave.

Guzman, who works as an office manager for a civil rights organization in Salt Lake City, also earned a master’s in human rights law in 2017 from Saarland University's Europa-Institut in Saarbrucken, Germany.

She recently applied for advance parole again, this time to work on a second master's at Leiden University in The Hague, Netherlands.

The courts could terminate DACA while she’s studying abroad. Guzman, 30, knows there is a risk she might not be allowed back in the United States.

If that happens, she said, she is prepared to reluctantly stay in Europe and pursue her dreams there.

She wants a job with the federal government

By Bill Keveney, USA TODAY

Andrea Rathbone Ramos’ dream job is to work for the federal government. She has the credentials: a prestigious education, a fellowship with the U.S. Hispanic Chamber of Commerce and an internship with the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute. But she can’t land a job without permanent resident status or U.S. citizenship.

Rathbone Ramos’ first memory of government came as a young teen in San Antonio, Texas, when she followed a 2010 Congressional effort to adopt immigration reform. The measure ultimately failed, but she was electrified by the idea that lives could be changed by policy.

Rathbone Ramos, a 26-year-old DACA recipient, was born in Mexico City and came to the United States at the age of 9. After graduating with honors from the University of Texas, San Antonio, she enrolled in New York University’s Wagner School of Public Policy to obtain her master’s degree, her admissions application bolstered by an essay on being the child of immigrants.

Over the years, one of her most meaningful pursuits has been traveling to Washington, D.C., where Rathbone Ramos has met with a range of U.S. senators, from Republicans John Cornyn and Ted Cruz to Democrats Dick Durbin and Bob Menendez, to advocate for immigration reform, including a path to citizenship for DACA recipients.

Looking back at her 16-year-old self working in a San Antonio mall, Rathbone Ramos said she couldn’t have imagined where she would be today. She knows DACA’s limitations and the opposition immigrants face in the United States, but she also sees it as a land of hope.

“This country hasn’t fully promised me anything, but it has given me a taste of what it can offer,” she said. “I have yet to know any other country in the world that allows a young undocumented woman to chase down senators on Capitol Hill.”

‘My whole family and I started crying’

By Danae King, The Columbus Dispatch

Sam Murillo got straight As, participated in extracurricular activities and took every Advanced Placement class available at her high school in Jeffersonville, Indiana.

But guidance counselors told her that because she was undocumented, finding a scholarship to college wouldn't be possible. She should just get a job, they said.

Murillo searched online for "scholarships for undocumented students." She found three, applied and waited.

Four months later, a large yellow envelope came in the mail. It was March 31, 2017 – her 18th birthday.

When she opened it, she felt an overwhelming sense of shock and joy. She had been awarded a full ride to Trinity Washington University in Washington, D.C., from TheDream.US, a college access program for DACA recipients.

"It was honestly just like the best birthday present ever," she said. "My whole family and I started crying."

That excitement wouldn't last.

In August 2021, her status expired after political delays prevented the government from renewing it on time. Despite her efforts – and paying the $495 filing fee three times – it took more than four months to get her status back.

The immigration limbo cost Murillo her first job out of college at an education technology company. She broke down crying.

Although she landed another job as an associate scientist at a health care lab in Washington, where she tests blood samples for HIV, she worries it could be just a matter of time until another DACA delay leaves her without a paycheck.

Murillo, 23, has considered moving to Mexico. She and her family left there when the economy crashed in 2007 when she was 7. It's a country she knows little about.

"The fact that I have to think about that would be crazy," she said.

‘You never tell anyone you don’t have papers’

By Bill Keveney, USA TODAY

After arriving in Boston from El Salvador as a 9-year-old, Estefany Pineda didn’t understand what it meant to be undocumented. She just knew she wasn’t supposed to talk about it.

“My parents were always like, ‘You never tell anyone how you came here. You never tell anyone you don’t have papers’ – in Spanish, we say you don’t have papers,” she remembered. “I didn’t know what was wrong with me not having papers. I just knew it was something bad that I shouldn’t tell anybody.”

Pineda, 24, who fled El Salvador with family members after a death threat in 2007, was able to attend college with an Unafraid Scholarship, designed for students who can’t receive federal aid because of their immigration status. She lived up to that scholarship’s name on her first day of college in 2017. It was the same day President Donald Trump announced his intention to end DACA.

“It was devastating. ... And I was like, ‘Why not share my story?'" said Pineda, who agreed to her first media interview only if she could use her middle name and be photographed from behind.

Pineda’s voice has grown stronger as she's become more open about her status. She received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in May and now works on behalf of other immigrants as membership coordinator of MIRA, or the Massachusetts Immigrant & Refugee Advocacy Coalition.

“I feel extremely empowered. I have a platform. I made an impact, one way or another,” she said. “I always hold within myself that it’s not just me, but thousands of people around me that maybe don’t get the chance to tell their story. I am doing that for them as well.”

She was forced to leave college

By Rick Jervis, USA TODAY

The tuition bill was a staggering $20,000 for the semester. Nour Kalbouneh stared at the University of Wisconsin-Madison billing statement in shock. Why was she being charged an extra $14,000 for international student tuition when she had spent most of her childhood in Wisconsin?

Kalbouneh met with the bursar’s office. Obviously, there has been a mistake, she said. She was from Milwaukee.

The official was polite but firm: Without legal immigration status, she had to pay international student rates.

By winter break, Kalbouneh and her father were moving her stuff out of the dorm. She could no longer afford her dream school.

“It was a really hard time,” she said.

Since arriving in the United States from the Palestinian territories at age 5, Kalbouneh has done all the right things. She stayed out of trouble, got good grades, graduated high school and received DACA at 18. The hurdle in Madison was unexpected.

She spent the next few years working odd jobs – at the Edible Florist and Starbucks – then stumbled upon TheDream.US, a group that provides scholarships to DACA recipients. With their help, she was able to attend and graduate from Eastern Connecticut State University with a political science degree. Fueled by her earlier setback, she graduated with a 4.0 GPA, was class president and gave the commencement speech at graduation.

Today, Kalbouneh, 26, works at the ACLU of Wisconsin, helping individuals on civil rights issues, including other immigrants. Next up is law school, which she’ll apply to in the fall, then working to exonerate inmates unjustly prosecuted and ultimately a career as a law professor.

DACA has been invaluable, she said, but she still can’t travel abroad or vote.

“It’s a short-term solution for a long-term problem,” Kalbouneh said. “It’s not enough.”

*

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: DACA news: Is immigration program still working 10 years later?

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies