‘There’s going to be no fishing.’ Can Mississippi marshes be saved from sea level rise?

Chris Lagarde and David Resor knew a man-made canal was widening in the Hancock County marsh, but they had no idea just how much marsh had been lost over two decades.

Resor had been fishing the marshes since the 1970s, while Lagarde worked in the 1980s as a field biologist tagging redfish at the canal’s mouth in Heron Bay. Like others attuned to the value of Gulf Coast marshes, they have been watching them shrink.

The canal, dug decades ago for a gas pipeline, was at least twice as wide as it had been on their last visit to Heron Bay more than 15 years earlier, they said.

Lagarde had been hopeful the state would fill in the canal after the 2010 BP oil catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico, when he was working as special assistant for fisheries and natural resources for then-U.S. Rep. Gene Taylor. BP and other responsible parties would pay billions to the Gulf states for the environmental damage a ruptured oil well caused.

“When it first became evident there would be a (BP) settlement, the consultants, the counties, everybody, they all had lists of projects that hadn’t been funded,” Lagarde said. “They all had ideas of what they wanted to spend money on and one of them was filling the pipeline canal.

“It might have been my idea. It made sense. Because the pipeline canal was a man-made ditch, it seemed to me to be a good idea to fill it. It was always in my craw that thing was getting bigger and bigger.”

Lagarde believes the state took the path of least resistance, choosing a project on Heron Bay that everyone could get behind while leaving the canal untouched. The canal is a convenience to fishermen who use a nearby marina and shoot straight through the shortcut to fertile Louisiana fishing grounds.

“This is that fight between what man wants to do and what man should do,” Lagarde said. “They should fill it in, but it’s not going to happen.”

Multiplying this scenario – want vs. need – across Louisiana and Mississippi equals more eroding marshes, says Lagarde, who grew up crabbing from piers on the Bay of St. Louis and went on to a degree in fisheries management.

“We’re faced with a dilemma as a society,” Resor said. “It becomes economics vs. conservation. You want to facilitate growth in business, but at the same time, you’ve got to protect the environment.

“That’s what the problem is. There’s no one thinking about the common good. Not necessarily that pipeline canal, any pipeline canal needs to be filled in. It’s pervasive in society right now. You’re looking for short-term rewards vs. long-term rewards. Eventually, there’s going to be no fishing.”

On average, the Mississippi coast has been losing more than 200 acres a year of salt marsh and other coastal habitats since the 1850s, according to the Mississippi Department of Marine Resources. The state lost 10,000 acres of wetlands in the 60 years from 1947-2007, the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality calculated.

Development over the past century, rerouting of rivers that built tidal marshes, hurricanes, dredging of navigation channels, and compacting and sinking of marsh foundations have all contributed to Mississippi’s loss.

Unless carbon emissions decrease, sea level rise will cause northern Gulf marshes in Mississippi and offshore barrier islands to collapse into open water as early as 2070, said Patrick Biber, who has studied marshes extensively and works as an associate professor at the University of Southern Mississippi’s Gulf Coast Research Lab.

With high carbon emissions, sea levels will be 1.5-2 feet higher by 2060. “That is about the elevation we expect to see our marshes flooded,” he said.

With them will go nurseries for shrimp, blue crab, oysters, redfish, speckled trout, mullet and other finfish species, and habitats for birds – marine life that makes the Mississippi Coast a special place to visit and fuels tourism.

Coastal marshes on the mainland and the barrier islands also store carbon that would otherwise contribute to global warming and filter pollutants such as nitrates from the water.

Examples abound along the northern Gulf of negative consequences from the best-laid plans to tame marshes and the rivers that feed them sediment, for public safety, profit or convenience.

Lowering carbon emissions would increase the likelihood that marshes unimpeded by roads, rail, bulkheads and other development could migrate before they drown.

Scientists and those attuned to marshes see they must be managed in a way that works with nature, for survival’s sake. Mississippi is using millions in BP money to shore up marshes and even recreate one of several islands that have already disappeared offshore.

“Marsh is often the thing that’s between us on high ground and water,” said Robert Smith, coastal program coordinator for Wildlife Mississippi and an avid watcher of marsh birds.

“A lot of times, it doesn’t have a hard bottom. It’s got pokey black-tipped needle rush in there. It’s not a comfortable place to be for us, but that marsh serves a whole lot of important functions.

“It’s where all the phytoplankton and algae and things are, and all the little crabs and crustaceans and small shrimp survive on those things. And then the larval fish eat those things and the bigger fish eat those things. It’s the base of our food web.”

Early Coast development destroys marshes

Beaches in the three Coastal counties of Hancock, Harrison and Jackson are, for the most part, an artificial construct created to stave off flooding of a beach roadway and waterfront property

“The beach is not our natural shoreline,” said Carlton P. Anderson, research scientist at the Gulf Coast Geospatial Center, who has extensively studied marshes. “It’s not.

“In fact, I don’t really want to speculate, but it would probably look more like the north shore of Cat Island than anything, which is a mixture of forest, marsh, some natural beach, but it’s a mix.” (Cat Island is a barrier island near shore in Biloxi.)

Early development along the Mississippi Coast is described in a paper published in 1991 by the Geology and Geography Department at Mississippi State University. Before the mid-1800s, the Coast’s population was relatively low, with 770 inhabitants recorded in 1811. But by the mid-1800s, tourists from New Orleans and Mobile began to discover the area, with hotels and summer homes constructed.

In the second half of the 19th century, rail lines, a port with a ship channel dredged between Ship Island and Gulfport, along with a budding seafood industry, increased the population.

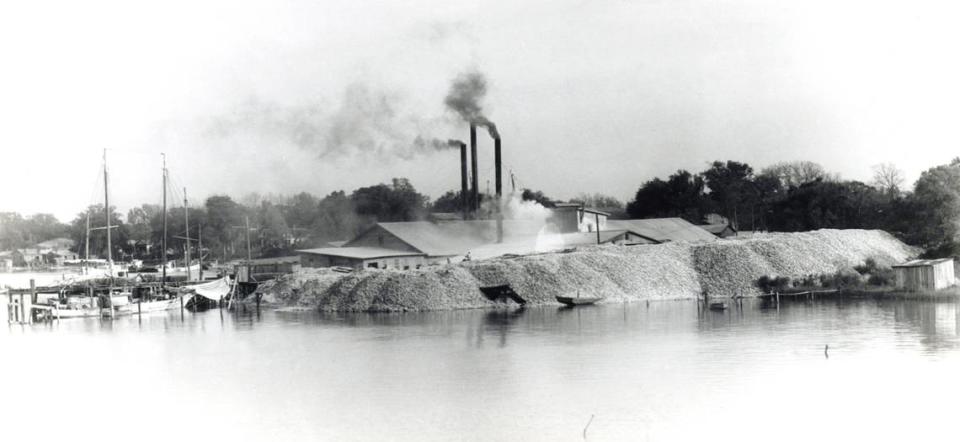

The first seafood canning factory opened in 1881 on Biloxi’s Back Bay.

“By 1902, . . . 12 canneries reported a combined catch of 5,988,788 pounds of oysters and 4,424,000 pounds of shrimp,” Deanne Stephens, a University of Southern Mississippi history professor on the Coast, notes in a feature story for the Mississippi Historical Society. “By 1903, Biloxi, with a population of approximately 8,000, was referred to as ‘The Seafood Capital of the World.’ “

A beach road, literally paved with oyster shells, also took shape. In the early 1900s, Coast counties began building seawalls to protect the beach road and property during hurricanes. When beach vegetation and sand south of those seawalls disappeared, artificial beaches were created to buffer the vulnerable seawalls from hurricanes.

By 1951, Harrison County’s beach stretched across 26 miles and was at that time promoted as the longest man-made beach in the world. Millions are spent to maintain county beaches and shore them up after storms.

The seawalls eventually choked inlets and marshes that once lined the waterfront, along with intermittent stretches of sand.

“Every time we built a seawall, we destroyed the ability of those marshes to remain alive and productive and to accrete as sea level rises,” said Gerald Blessey, a Biloxi native, former state legislator and mayor.

“It does have the benefit of jobs and business, so there’s a balance there.”

“The seawall and the sand beach occurred long before there was a consciousness about these things at a level that would make a difference in public policy making. The consciousness is still not fully there.”

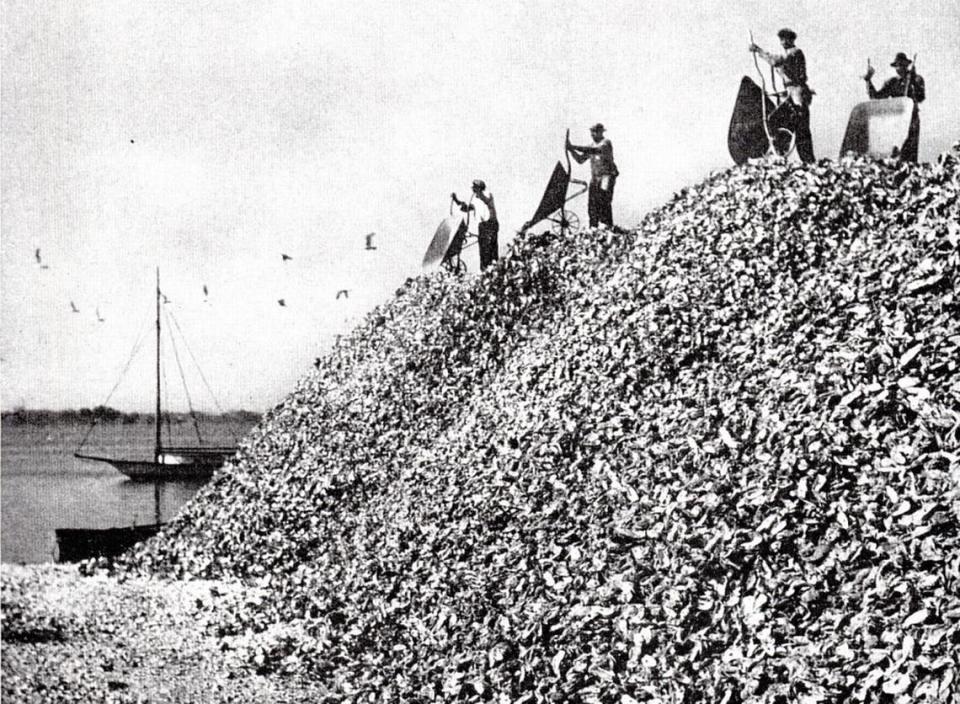

The seafood factories also made use of the oyster shells that, in historic photographs, were mounded like mountains around the properties. Those shells were tossed in the wetlands and converted to solid ground, said Joe Jewell, who, like Blessey, grew up in East Biloxi where the factories were located.

“It created a new area for them,” Jewell said. “You could truck dirt on top of it. Now you’ve got another platform for a factory or an oil dock or something closer to the water because everything was water access back then.

“Wetlands weren’t considered high-quality real estate. They weren’t considered environmentally critical or essential habitat types. Docks were built over them, fuel docks were built over them, transfer of fuel from dock to boat, spillages, there was no big regulation back then. These factories had to have more and more water access and in order to do that, they began filling wetlands.”

Blessey says seafood companies filled only a small portion of the wetlands that no longer exist. He points out that 456 acres of state tidelands on the Pascagoula waterfront were filled at Ingalls Shipbuilding, the state’s largest manufacturing employer. Another 209 acres of tidelands went to develop Gulfport’s state port, records from the secretary of state’s office show.

“It used to be that filling wetlands was encouraged,” said Robert Wiygul, an Ocean Springs attorney who specializes in environmental law. “That was considered taking unproductive property and making it productive.”

“They were making solid land there. Everybody thought, ‘That’s good.’ ”

Legislature tackles MS marsh preservation

Residential development also has contributed to the destruction of wetlands. As the Coast’s population grew, homes were built on the Back Bay of Biloxi and Bay of St. Louis, and along rivers in all three Coast counties.

By the time Gerald Blessey joined the state Legislature in the early 1970s, fishermen were complaining to him about all the wetlands being filled for waterfront subdivisions.

Between 1930 and 1973, 8,170 acres of coastal marsh were filled for industrial and residential use, a marsh inventory from the state Department of Marine Resources concludes.

“Shrimping had declined some,” Blessey said. “It was clear the ecosystem was in distress.”

For developers, filling wetlands offered free land that could then be sold to homebuyers.

“Real estate companies were filling them in rapidly,” Blessey said.

To preserve wetlands, Blessey authored the 1973 Coastal Wetlands Protection Act. The law’s stated purpose was to recognize the value of Coastal wetlands and their ecosystems, and regulate their development, declaring they should be preserved unless a higher public purpose is served.

“Filling in for residential lots is not a higher public purpose, never was, never will be.” Blessey said. “It’s so hard to get policy like that to be applicable. You have exceptions and a lot of bulkheading still. But it did restrain development.”

Bulkheads and other shoreline stabilization devices meant to protect waterfront property from erosion can lead to marsh loss. Like highways and rail lines, the hardened structures also prevent tidal marsh from migrating upland as sea levels rise. Boat wakes also contribute to marsh erosion, said Eric Sparks, director of Mississippi State University’s Coastal and Marine Extension Program.

He has been working with property owners to install “living shorelines,” an alternative to bulkheads and hardened shoreline stabilization. Sparks said more than 62 percent of private property on Back Bay has been hardened with bulkheads, seawalls and the like.

Back Bay includes fringes of marsh along the shoreline and on small islands in the bay, with more substantial areas of marsh on the western end.

One successful living shoreline has been established at Camp Wilkes, a nonprofit youth campground on the bay’s north shore. A bulkhead along the camp shoreline had failed and the land was eroding rapidly.

MSU’s Coastal Research and Extension Center and The Nature Conservancy worked with Camp Wilkes to install a living shoreline. A breakwater of concrete blocks was installed just offshore.

Behind it, along the shore, volunteers planted smooth cordgrass and black needle rush most commonly found in area marshes

On a recent boat trip to the Camp Wilkes shore, Sparks pointed out how well the living shoreline has held up. Marsh grasses filled in quickly between the breakwater and shore.

“This one’s gone through several hurricanes,” he said, “and it looks better than it did when we put it in, unlike the bulkheads across the way. We haven’t touched this since we installed it.”

A cost-benefit analysis concluded the Camp Wilkes living shoreline is three times more cost effective in the long term than a bulkhead because of maintenance and repair costs. Also, bulkheads must be replaced every 25 years or so, while living shorelines are designed to last indefinitely.

“I didn’t have a clue what a living shoreline was,” said David Stanovich of Biloxi, who was president of Camp Wilkes at the time. “He sold us on it. I was a little skeptical at first. It’s been through a couple of storms. I don’t think we’ve lost a block on that living shoreline. It’s done what it advertised. It was going to foster more aquatic growth and shouldn’t have to be replaced unless something catastrophic happens.

“We haven’t had any more erosion problems. It basically looks like it did when they put in the living shoreline and we’ve had some high tidal surges.”

He said the camp lost its pier this summer in Hurricane Ida. “But that living shoreline didn’t budge.”

Living shorelines replace bulkheads

State agencies are employing the living shorelines concept on a larger scale to stave off erosion of the Coast’s largest and most endangered tidal marshes.

Both the Hancock County Marsh Preserve, at 20,909 acres in southwest Mississippi, and the 18,000-acre Grand Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve on the southeast side of the state are included in Coastal Preserves protected from development as “crucial coastal wetlands habitat,” according to the Department of Marine Resources.

In the Hancock County marsh, the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality undertook its $50 million living shorelines project with BP restoration funds. The project installed six miles of breakwater, including a stretch along Heron Bay, to absorb wave energy, 46 acres of marsh created inside a containment berm with sediment dredged from Hancock County’s Port Bienville and a 46-acre oyster reef planted in the bay to further absorb wave action and grow oysters in an area that was once highly productive.

The marsh was eroding at a rate of 6-10 feet annually in the area where the new marsh was created, according to the Department of Environmental Quality. Vegetation is already growing on the marsh, which was a big mud flat in May after all the sediment was pumped in.

“The living shorelines (breakwaters) constructed as part of the project are reducing shoreline loss by an average of approximately 89 percent across the project site compared with pre-construction shoreline erosion rates, and in some areas we are seeing shoreline accretion,” Valerie Alley, division chief for MDEQ’s Office of Restoration, said in an email to the Sun Herald.

The marsh remained intact during Hurricane Ida, she said, which made landfall Aug. 29 in Louisiana. Ida hit Hancock County as a tropical storm with a tidal surge of 8.7 feet and a sustained wind speed recorded at 67 mph.

The oyster reef completed in 2017, has not fared as well. Oysters were growing on the breakwater and the reef, but they all died in 2019, a monitoring report said. Salinity levels dropped too low for oysters to survive in Heron Bay and the western end of the Mississippi Sound, where most public reefs are planted, because the Bonnet Carré Spillway in Louisiana was open for a record 123 days.

The spillway releases Mississippi River water into Louisiana and Mississippi waterways to prevent New Orleans from flooding after heavy rainfalls, lowering salinity to intolerable levels for the oysters. The same thing happened in 2011.

Mississippi has produced an average of 1.4 million pounds of oysters per season since 1950, federal fisheries landing data shows. But no oysters have been caught on the state’s public reefs since Dec. 8, 2018, MDMR records show. The reefs are decimated and being restored, with no forecast for when they might reopen.

Grand Bay’s unique marsh worth saving

The Grand Bay marsh appears to be the most studied in the state. PVC pipe rises from many points in the marsh where scientists are measuring erosion, elevation, gains in sediment and other features, or conducting various studies.

“Grand Bay is very unique, in that we don’t have much development,” said Jonathan Pitchford, the MDMR’s stewardship coordinator on the reserve.

“A lot of places where marshes migrate upland, they hit a barrier, like a road, and they can’t move above it. We don’t have that, so we’re a great place to study marsh migration as sea level rises.”

Grand Bay is losing up to 16.4 feet of marsh a year. Sediment from rivers builds marsh, but Grand Bay only receives sediment carried by waves from the Mississippi Sound and small amounts from upland areas.

Barrier islands that protected Grand Bay from storm surge, including hurricanes, have shrunk or disappeared. Grand Batture Island, closest to the marsh, is now nothing more than a sandy shoal.

“Actually, it will probably be gone before long, Pitchford said of the island. “It’s probably going to disappear in the next couple of decades.”

Sea level rise also contributes to erosion. Sea level rose by 1.54 feet over a 157-year period in the Mississippi Sound, a 2015 scientific research paper concluded, further eroding the shoreline.

Projects to slow erosion, including living shorelines and 9.5 acres of artificial reefs installed this year, are ongoing. But the decline of this unique marsh is inevitable.

“There are several models that show us pretty much being underwater in 60 years,” Pitchford said.

But, he added, sea-level rise forecasts come with some uncertainty.

“Considering how far into the future we are aiming to predict,” he said, “all the potential scenarios, and a huge number of variables that are in play with regard to how marshes respond, I have a hard time deciding what the future will look like.”

People still have a choice about how fast Coastal marshes will shrink. Lowering the dependence on fossil fuels is key, scientists who study the marshes say.

“We see this kind of change where we lose a lot of these coastal assets, the islands and marshes, being a pretty likely future if these emissions continue the way they are,” said Biber, the University of Southern Mississippi professor.

“Really, right now, the uncertainty is what we as a society decide to do about this.

“We know the consequences of our actions, but we’re not doing a very good job of addressing the problem and changing our behavior.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies