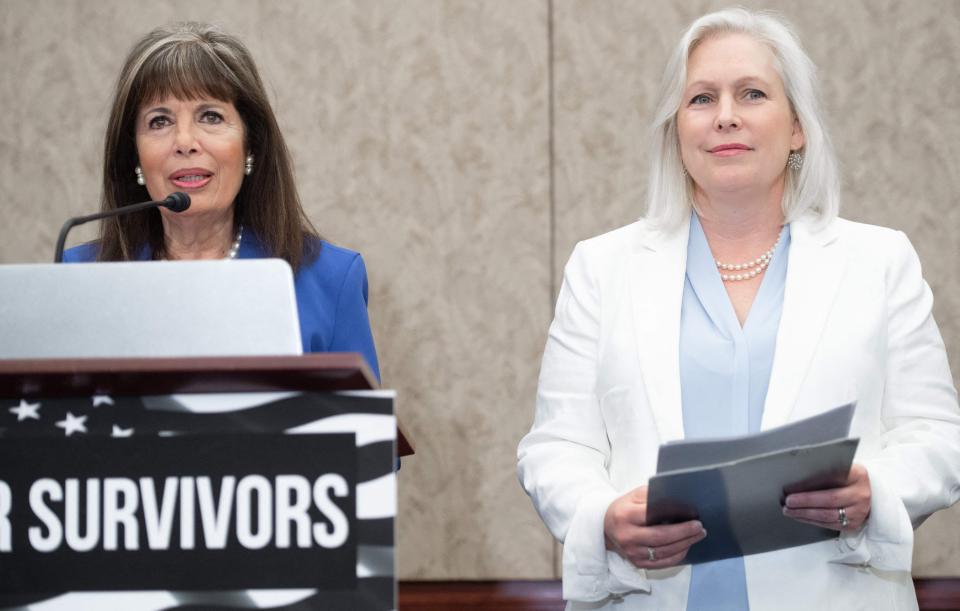

Gillibrand speaks out on military sexual assault – again. But this time it might be different

WASHINGTON – Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., has never been closer to her decade-long goal of changing the way the military prosecutes sexual assault cases.

There’s a near certainty that commanders will no longer have the final say in prosecuting sex crimes in the military. Specially trained prosecutors would make those decisions under a bill approved by the Senate Armed Services Committee last week.

Gillibrand won approval of a measure that would go further and remove military commanders' authority to prosecute all serious crimes. She has the support of a majority of senators for that measure. A competing proposal, also in the bill and supported by the Pentagon, would limit the reform to sex crimes.

Gillibrand and Speier: We're closing in at last on fixing how military handles sexual assault (Opinion)

A consensus between the Senate and House will be reached as the National Defense Authorization Act is must-pass legislation. Bottom line: It's virtually guaranteed that the fate of alleged sex offenders will no longer rest with commanders but with prosecutors.

"I'm extremely confident there will be major reform this year," said Don Christensen, president of the advocacy group Protect Our Defenders and a former chief prosecutor for the Air Force. "How far it will go and what it looks like is yet to be determined, but at a minimum, commanders will no longer be making prosecution decisions for sex assault and rape cases."

In an interview with USA TODAY, Gillibrand, who chairs the Senate committee's personnel panel, talked about the necessity for change in light of the Pentagon's inability to protect its own from sexual assault.

"We believe that creating a more professionalized or highly trained and unbiased system of justice is appropriate, given the lack of success that the military has had," Gillibrand said. "The area where we have the most data is sexual assaults in the military. And we've been keeping data on that for 10 years, and over those 10 years, we've seen that the rate of prosecution is going down, the rate of convictions going down. But the prevalence rate of sexual assault is definitely the same."

Fact check: The numbers behind Gillibrand's military sexual assault claims

Sexual assault has long plagued the military. In 1992, the Tailhook scandal involved Navy aviators assaulting more than 80 women at a booze-soaked convention in Las Vegas. In its aftermath, the Navy secretary was fired, and the Pentagon adopted what became an oft-repeated but hollow pledge of "zero tolerance" for sexual assault. In 2013, Congress renewed interest in changing the system to protect sexual assault victims after the Pentagon reported that 26,000 troops were sexually assaulted in 2012 compared with 19,000 in 2010.

Gillibrand fought for several years to wrest the authority for charging sexual assault cases from commanders and allow trained prosecutors to make such decisions. Her cause gained more urgency in 2019 when the Pentagon reported that sexual assault had increased 38% from 2016 to 2018 with more than 20,000 crimes, ranging from groping to rape.

President Joe Biden's election in 2020, and his selection of Lloyd Austin as defense secretary this year, signaled change at the Pentagon.

This month, Biden said he supports removing decisions on sexual assault prosecutions from commanders.

“I look forward to working with Congress to implement these necessary reforms and promote a work environment that is free from sexual assault and harassment for every one of our brave service members," Biden said.

Austin also expressed support for removing commanders' discretion in sexual assault cases. An independent study commissioned by the Pentagon recommended it as well. Some military leaders have told Austin they fear the change would create additional bureaucracy and delays.

The U.S. military justice system evolved during the past century to resemble proceedings in a federal courtroom, with prosecution, penitentiary standards, witness testimony and trial by jury before a trained judge. One major exception: The decision on whether charges should be brought, who sits on the jury and whether a conviction or punishment can stand is controlled by a high-ranking officer who is the defendant's superior. The officer is not a lawyer nor a judge, although he or she receives written advice from a military attorney.

Gillibrand favors changes that go deeper than removing commanders' authority in sex crimes. Cases of crimes with terms of more than one year in prison would be referred to trained prosecutors under her proposal. Within that prosecutor's office would be a special unit dedicated to sexual assault cases. The model would be akin to the Manhattan district attorney's office, she said.

"When we wrote the bill, initially, we met with military experts, and we met with advisers on military justice," Gillibrand said. "They said that the military justice system works best with bright lines. In fact, when other countries reformed their military justices, they chose a bright line on all serious crimes, any crime that has more than a year of whether your punishment if convicted."

Serious crimes are often related, Gillibrand said, pointing to the case of Army Spc. Vanessa Guillen, who complained of being sexually harassed before she was murdered by a fellow soldier at Fort Hood in Texas.

Fort Hood: Vanessa Guillen shows 'the military hasn't had their Me Too movement yet'

The short-term success of her reform, Gillibrand said, will be an increasing number of sex crime cases going to trial and ending in conviction. An increase in unrestricted sexual assault complaints, cases that can result in criminal charges, would show confidence in the military justice system, she said.

“Over time, I'd like to see the rate of assaults go down,” Gillibrand said. “Because my theory is, and the theory of many criminal justice experts is, if you start convicting predators, not only can they not become recidivists, but also it sends a very strong message that this crime is not tolerated. The crime will be adjudicated, and you will be held accountable. Today the message is ‘you can get away with it.’”

Eugene Fidell, who teaches military law at New York University, said he favors the broader reform proposed by Gillibrand that would empower trained military lawyers to make decisions on charging all serious crimes. The standard of one year in confinement, he noted, is the dividing line between misdemeanors and felonies. Having legal experts make the decision to file charges in such cases will increase confidence in the system by victims, the accused and the public, he said.

Commanders' time is better spent on military issues, he said: "I'd rather have them concentrate on operational matters."

More:

A soldier was allegedly raped and died by suicide. Her family says it's a hate crime.

The National Guard welcomes women. Until they report sexual assault.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: NDAA poised to remove commanders from military sexual assault cases

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies