This Fort Worth marketing whiz turned coin collecting into a mainstream hobby.

B. Max Mehl, an immigrant lad who clerked in a shoe store for 25 cents a week, made a fortune from small change. When customers paid, he examined their cash for rare pennies, nickels, dimes and half dollars.

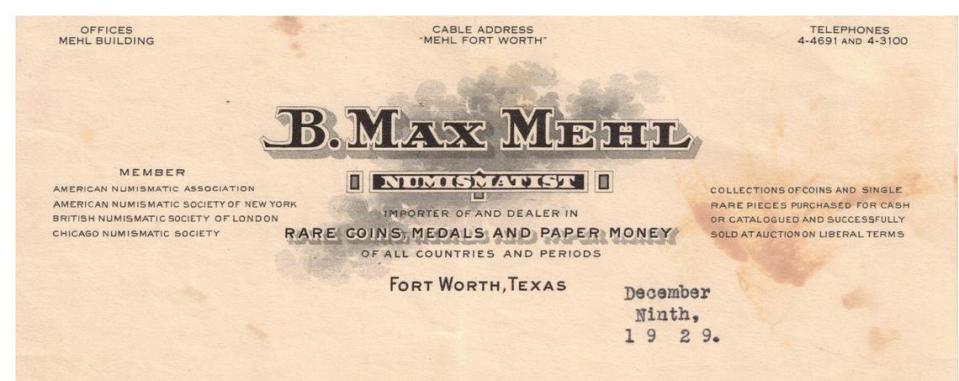

In 1903, he placed an ad in The Numismatist, a coin collecting magazine, and sold his vintage coins to the highest bidders. A year later he ran classified ads in the Fort Worth Telegram. In 1906 he held a coin auction by mail and promoted his business with five lines in Colliers magazine, becoming the first coin dealer to advertise in the popular press. Within a decade, Mehl had turned coin collecting into a hobby for the masses.

Before Mehl popularized numismatics, it was a pastime for the wealthy, an obscure subject of study for scholars of archaeology and art. Mehl was no scholar — he had dropped out of Central High at age 16. But he was a keen observer, a promoter on a par with P.T. Barnum. Capitalizing on the possibility that people had treasure in their pockets, he offered $50 for a 1913 liberty head nickel, although he knew none were in circulation .

The publicity led trolley conductors and salesclerks to scrutinize coins before adding them to the till. In a booklet titled “The Romance of Money,” Mehl reported that his quest for a rare copper penny had turned into a $200 bonus for a college student who needed the cash to cover tuition. A gold dollar coin that he sought eventually surfaced in Australia. By 1912, Mehl had a staff of 10 handling correspondence from around the globe.

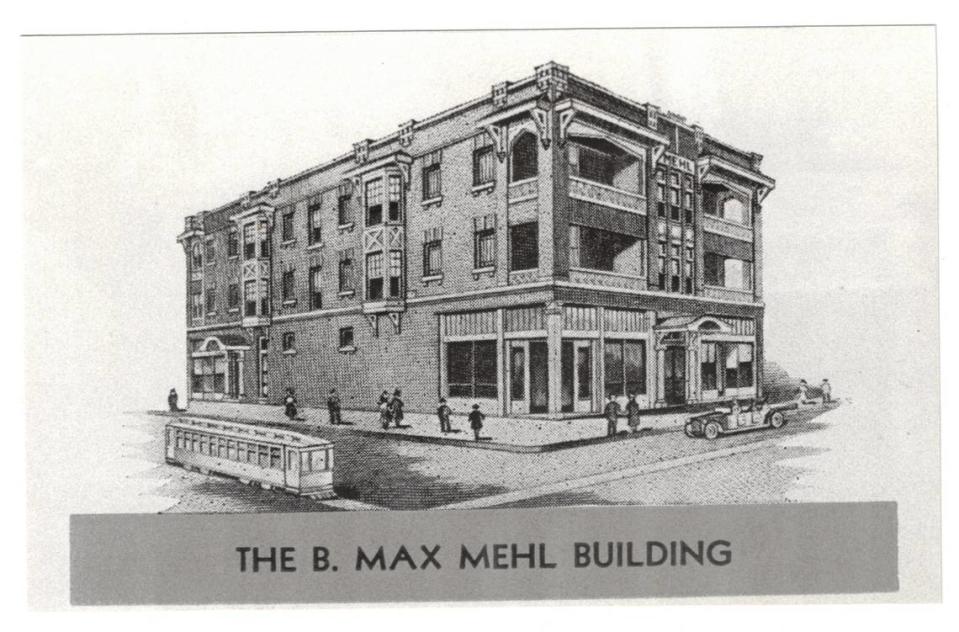

In 1916, Mehl hired local architect Wiley G. Clarkson to design a three-story, 16,000-square-foot office building at 1200 W. Magnolia Ave. and South Henderson Street. Constructed of red Acme brick and accented with cast stone, the Max Mehl Building’s facade featured bay windows and doors and windows crowned with bas reliefs of antique coins. Inside the handsome landmark, 40 employees answered letters and sent Mehl’s annual catalog, the Star Rare Coin Encyclopedia, to a subscription list that grew to 70,000.

During the Depression, when Mehl advertised on 50 radio stations, his incoming mail peaked with 1.25 million inquiries in 1935. The Fort Worth post office added trucks to the Magnolia Avenue route because Mehl’s “advertising campaigns accounted for more than half the mail,” according to the Encyclopedic Dictionary of Numismatist Biography.

Among Mehl’s famous clients were Amon Carter Sr., Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and King Farouk of Egypt.

The teenage shoe clerk whose first job paid 25 cents a week had come a long way from Panevezys, Lithuania, where he was born in 1884. His full name was Benjamin Maximillian Mehl. With his parents, three older brothers and sister, he had emigrated in 1892, initially to New York, then to Fort Worth, where it is likely that his mother, Ruchel Goldstick Mehl, had relatives.

In 1907 he married Ethel Rosen, the niece of Northside developer Sam Rosen, who also had roots in Lithuania. The wedding was in the parlor of Sam Rosen’s home, with a Dallas rabbi, S. Margolis of Congregation Shearith Israel, officiating.

Max and Ethel Mehl had two daughters, Lorraine (Rosenberg) and Danna (Levy), who became the family archivist.

Mehl’s granddaughter Roslyn Levy Rubin still resides in Fort Worth and remembers her grandfather’s generosity. “He was my ‘Pappa,’” she said in a recent phone call. “He was always handing me coins.” Whenever the family gathered for dinner at Colonial Country Club, where Mehl was a charter board member, “he’d give me a nickel to play the slot machines” — a popular amenity at private clubs during the 1940s. The glint and jingle of coins continued to fascinate her “Pappa.”

As Mehl’s fame and fortune grew, so did his civic involvement. He was president of the Rotary and the Exchange Club, which holds an annual roast to goad the city’s wealthiest men to donate to the Star Telegram’s Goodfellow Fund at Christmas. During World War II, he chaired a local Selective Service Board. The Fort Worth chapter of the National Conference of Christians and Jews honored him with a humanitarian award in 1956.

Following Mehl’s death in 1957, the coin dealership remained in operation until 1961. The Max Mehl Building gradually deteriorated into a flophouse with low-rent apartments. Renovated in 2007, the building is part of Fort Worth’s Fairmount-Southside Historic District, a neighborhood listed since 1990 on the National Register of Historic Places. Suites in the building are leased at $20 to $22 per square foot. Tenants include lawyers, physicians, surveyors, research firms, real estate agents, and a photo studio. Though no longer a clearinghouse for coins, the landmark remains a footnote to numismatic history.

Hollace Ava Weiner, a former Star-Telegram reporter, is an author, archivist and director of the Fort Worth Jewish Archives.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies