Former head of Colchester RCMP testifies at mass shooting public inquiry

As a protest happened Thursday by some family members of the victims of the Portapique mass killing, a retired Mountie who in April 2020 was in charge of the RCMP detachment in Bible Hill, N.S., testified about efforts to seal off the small community where a gunman was killing neighbours.

Staff Sgt. Al Carroll first found out about a situation in Portapique, N.S., when his son, who was also a police officer, called him at home to give him a heads up.

At that time, Const. Jordan Carroll was working in Cumberland County and helped block off part of Highway 2 west of the entrance to the subdivision where the violence started.

That evening, a gunman attacked neighbours, killing 13 people before driving away in a decommissioned police car he'd designed to look like an actual RCMP cruiser. The following morning Gabriel Wortman killed nine more people: acquaintances and strangers, including a pregnant woman and an RCMP officer.

The senior Carroll answered questions Thursday via Zoom after the commission overseeing the public inquiry granted an accommodation. In its decision, the commission didn't explain the exact reasons for the him appearing virtually, but said it considers private health information.

The National Police Federation and Canada's attorney general had requested that Carroll appear in person, but said he should only answer questions posed by the inquiry's lawyers.

The commission decided he will still have to answer questions posed by lawyers for families of the victims, though some are boycotting proceedings in response to the decision that two other senior officers will be allowed to testify in pre-recorded sessions and won't face any cross-examination.

Carroll was just shy of 40 years of service with the Mounties that spring and as detachment commander his role was predominantly administrative — overseeing the detachment's staff of 34 officers — but the night of April 18, 2020, he put on his uniform and headed to the office to help.

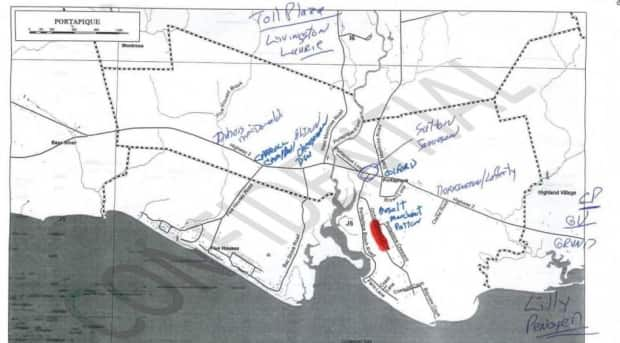

In the early hours, Carroll helped with positioning officers in the Portapique area and efforts to close off exits.

Commission counsel Roger Burrill asked about a radio broadcast at 10:48 p.m. from Const. Vicki Colford where she explained a woman whose husband the gunman had injured told her about a possible back way out of the subdivision.

She said: "Millbrook, if you guys want to have a look at the map, we're being told there's a road, kind of a road that someone could come out, before here. Ah, if they know the roads well." Only later would police determine the gunman drove out a private road along a blueberry field, likely escaping a few minutes before Colford's broadcast.

Carroll said the audio played during the public inquiry proceedings was the first time he heard the communication. He said the radio transmission could have occurred when he was on the phone.

That night he moved to a makeshift command centre set up in Great Village, N.S., and worked closely with fellow staff sergeants Steve Halliday and Addie MacCallum. He worked into the next morning.

Drawing on maps while planning response

During Thursday morning's questions, Burrill also asked about the information Carroll was using while planning how to contain Portapique. Carroll said MacCallum consulted what he believed was Google Earth and they reviewed the topography of Portapique, including the blueberry field to the east of the main entrance.

"It looks like just a big field, just a big open field ... we're not seeing an egress point in that area," he testified. "We looked at what we had to look at. It showed nothing we could determine was an active roadway."

MacCallum previously told the commission he wasn't satisfied with the view on Google and felt it was out of date, "making roads where there's no roads." But he couldn't log into an RCMP satellite imagery program that night. Carroll said he had not been trained on that program as he planned to retire in May 2020.

Carroll said they were also relying on staff at the RCMP's Operational Communications Centre, where dispatchers worked and Staff Sgt. Brian Rehill was overseeing the response, because they had access to the RCMP program and could review it to look for egress points.

He and MacCallum also knew the area well and they took down a large map that had been hung on a wall of the detachment to use as a reference point, Carroll said.

Questions about command structure

Burrill also asked Carroll about Sgt. Andy O'Brien's role. As a non-commissioned officer in the Bible Hill detachment, O'Brien ran the day-to-day operations of the detachment.

Carroll testified he offered to help the night of April 18, after O'Brien told him he'd had a couple glasses of wine and though he wasn't intoxicated, wouldn't be going to the scene out of concern someone might spell the alcohol on his breath.

Carroll said he was later surprised to hear O'Brien's voice on the radio since he didn't realize he had a portable one at home, but he didn't have any concerns about O'Brien's ability to function.

At one point, O'Brien got on the radio and said he didn't want a second team on the ground in Portapique, N.S., to "avoid having anyone else in the crossfire."

"I thought Andy was just helping us out, monitoring and passing on information as need be to the rest of us," Carroll said in response to questions about the command role O'Brien had at that time.

Burrill said O'Brien's comment sounded more like providing directions to the front-line officers, to which Carroll replied that he perceived O'Brien as being concerned about safety and was pointing out danger.

But he did concede "it may have been a breach of command structure."

Carroll also acknowledged he "overstepped" his own role when he responded on the radio to his son's request for backup on a road west of Portapique's main entrance. But he said he would have "jumped in" if any officer was not getting a response on the radio and the fact that the constable was his son "had no relevance."

O'Brien and Rehill are both scheduled to testify next week, but will only be questioned by commission counsel next week in pre-taped video interviews, with the chance for other lawyers to submit questions.

'I should have asked more questions'

Later, lawyers questioned Carroll about his conversation with one of the officers who opened fire at the Onslow Belmont Fire Brigade. Const. Terry Brown called Carroll afterward to say he fired his service weapon.

Carroll testified he thought it was just the one accidental shot and asked if the team could continue searching for the gunman. He later learned that Brown and his partner, Const. Dave Melanson, both shot their carbines in the direction of a civilian outside the hall.

He said he stood by that decision to keep the team on the road given they were looking "for a madman out there shooting people." But he testified had he known what happened at the fire hall, he would have gone there personally to check in right away.

"It falls on me. I should have asked more questions. I was … just so content that nobody was injured and I didn't ask the questions I should have asked and that falls on me," Carroll said.

Family members protest

As Carroll began testifying virtually, about 20 people gathered to protest outside the Truro hotel where the inquiry was being held.

Family members and friends of the victims, as well as supporters of the families, are upset about the accommodations being made for Carroll and two other key RCMP officers involved in the shooting response.

"If the officers that were in charge those two days can't get on the stand and defend their decisions that they made, then there's something wrong with this whole process," Charlene Bagley, whose father Tom Bagley was killed in the mass shooting, told reporters.

"If they are not going to allow them to get up and speak the only truth that there is, then why are we taking part in this? Why has $26.5 million dollars been put towards this, for causing more trauma to the public and to the families?"

The group quietly marched on the sidewalk throughout the morning, holding signs that said "the truth hurts" and "don't hide behind the badge" as drivers honked in support.

The commission has said the accommodations are to help people with health or privacy concerns give their best evidence in a "trauma-informed" way.

But Bagley said it feels like the commission is not really thinking of the trauma of the other people involved — just the officers.

"That's all it seems to be. So their trauma seems to trump everyone else's. Not OK with that."

Some signs also called on Nova Scotia's premier to weigh in, reading "Houston we have a problem."

Premier Tim Houston told reporters in New Glasgow on Thursday that he listens carefully whenever the victims' families raise issues about the inquiry.

When asked about whether Houston could work with the federal government to ensure these concerns are being met, the premier said that the inquiry is an independent process and "we have to be respectful of that."

However, Houston said he's optimistic the commission is also receiving the message and will take the steps necessary to ease the concerns from families, Nova Scotians and politicians "all equally."

"Hopefully, we can find a way to get this back on track. The inquiry is really important that we get to the answers, so we just need everyone to have the confidence that everyone has the same goal," Houston said.

MORE TOP STORIES

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies