Forget grooming to Zoom – 18th-century men were first to make up

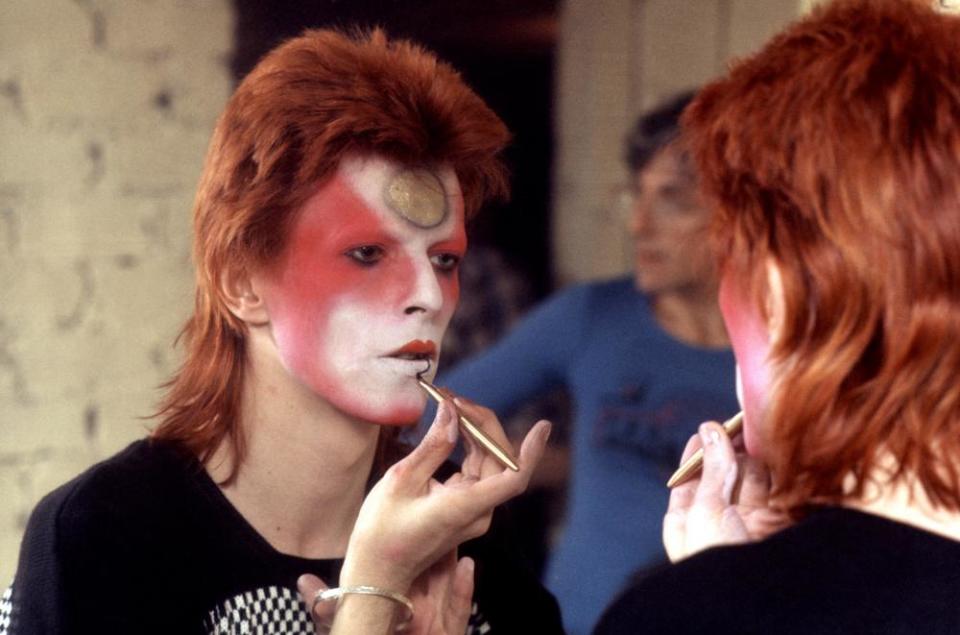

Male cosmetics are no longer the preserve of rock stars, with data showing sales are booming. But a new book by a historian at the University of Exeter reveals that far from being a modern trend, grooming products for men were popular centuries before being advocated by the likes of Russell Brand, David Bowie and Prince.

Dr Alun Withey says it all started in the 1750s. “The 18th century is actually the beginning of the market for men’s cosmetics that we see today,” he says, noting there was a “new focus on refining the body, so personal grooming becomes important”.

While the motivation to improve one’s looks might have been the same, the ingredients in the cosmetics were certainly not. Musca fly, hog’s gall and donkey genitals all went into 18th-century treatments, which were sold to soothe redness after shaving or to thicken hair.

Last week one online store reported a 300% growth in the men’s skincare market in the last six months of 2020, compared with the same period in 2019. In early 2020, Euromonitor predicted that the male makeup industry would be worth £49bn last year.

That forecast was pre-Covid and a further bump has come from men increasingly using cosmetics to hide blemishes and highlight mouths and eyes in order to be “Zoom ready”. The industry is so buoyant that Saturday Night Live recently parodied the hyper-masculine packaging of makeup brands like War Paint (with guest star Schitt’s Creek’s Dan Levy intoning such advertising slogan parodies as: “It smells like pepperoni! But it’s still makeup.”).

Unlike today, where the male makeup trend is led by internet beauty bloggers such as Jeffree Star , the cosmetics movement in the 1700s was more about economics. “There wasn’t a ‘movement’ as such, so no celebrity advocates,” says Withey, whose book is called Concerning Beards: Facial Hair, Health and Practice in England 1650 -1900. “It was more that men, and I think we’re talking about the middle class and elite men, had greater choice and opportunity to buy these things.”

Before this period, men’s use of cosmetics was frowned upon because of its associative use with women. “Satires depicted ‘macaronis’ or ‘fops’ who were sometimes described as using perfume, and the practice carried suspicions of effeminacy.”

Withey adds that shaving really changed things. “Shaving was an inherently masculine act, so shaving products were perhaps an acceptable outlet for men to use ‘product’,” he says, adding that it was after 1750 that men began to shave themselves instead of visiting a barber. “For men, shaving (became) very important in meeting new ideals of the ‘polite’ male body.”

However ‘polite’ the style was, the ingredients were anything but. “Donkey genitals were burnt to a powder, mixed with other ingredients and applied to the [shaving] rash. Odd as that might seem to modern eyes, the use of animal products in remedies was completely normal at the time,” says Withey.

He adds that historians of pre-modern medicine are wary of trying to look for “scientific” evidence of whether these treatments worked. “It’s more to do with what people at the time thought,” he says.

Like the SNL sketch parodying the marketing tactics of packaging men’s cosmetics in muted tones and minimalist designs, Withey says that shaving products had a specific customer in mind. “Razors were advertised using ‘hard’ imagery, such as control, temper and hardness, whereas shaving soaps and creams stressed luxury, unctuousness and scent.”

He thinks that the ideology behind the cosmetics of the time is the same as exists today. “The 18th century was a clean-shaven era, but the use of ‘product’ was encouraged both to help the process of shaving but also, in some ways, to make it almost an experience,” he says. “That is definitely the sort of thing we see today.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies