Fighting fire with fire: Controlled burns remain essential as US wildfires intensify

SAN BERNARDINO NATIONAL FOREST, Calif. – In 2015, the Lake Fire burned 31,000 acres in this popular hiking forest northeast of Los Angeles. It destroyed four buildings, came perilously close to the resort town of Big Bear Lake and took more than 1,900 firefighters five days to contain at a cost of almost $40 million.

Which is why it seemed counterintuitive to see some of those same firefighters walking along the forest floor in April with red drip torches deliberately sparking a blaze.

But the aim of the men and women of the U.S. Forest Service on this day was to prevent a repeat of the 2015 conflagration by reintroducing a natural process stamped out by humans.

"These forests were built to burn," said Garth Crow, the burn boss overseeing the 35 workers standing guard to ensure the prescribed burn stayed exactly where he wanted it.

As the United States faces what's expected to be a bad fire year and an even worse fire decade, such controlled burns – the epitome of fighting fire with fire – have been widely embraced as an essential component of forestland management.

Which is why forest ecologists are upset by a Forest Service decision Friday to stop all so-called prescribed burns on its lands for three months while an internal review of the practice is done.

The decision comes as an enormous fire in New Mexico, one part of which was touched off by a prescribed burn that got away, has torched more than 310,000 acres, burned hundreds of structures and displaced thousands of people.

“There’s a lot of politics in play,” said Matthew Hurteau, a professor at the University of New Mexico, who studies the effects of wildfires and climate change on Southwestern forests.

“After a plane crashes, we don’t shut down all air travel for three months,” he said. "The worst thing that can happen to our wildfire situation is that it get politicized."

The decision will affect the 193 million acres of land managed by the agency. Forest Service Chief Randy Moore called it a pause “because of the current extreme wildfire risk conditions in the field.”

He acknowledged that 99.48% of prescribed burns go as planned and said the forest service would conduct a national review and evaluation of its program during the three-month hiatus.

It’s the wrong message at the wrong time, said Lenya Quinn-Davidson, director of the Northern California Prescribed Fire Council.

"We in the West are in the midst of a fire crisis. Every year we lose more of what we care about: our communities, our forests, the ecosystem services that we depend on," she said. "The only thing that will get us out of this mess is more good fire, and every day we waste, the potential for serious losses grows."

Text with the USA TODAY newsroom about the day’s biggest stories. Sign up for our subscriber-only texting experience.

More, not less, fire is needed

After more than a century of suppressing fire at all costs – a strategy that made wildfires worse – the Forest Service in recent years has gotten religion on the benefits of prescribed fire. Combined with forest thinning, it is considered by many the gold standard of land management in overgrown forests.

"There are fine people that really don't want to see a single tree cut in the forest, but I think there's a large majority of people who realize to keep forests healthy we need to put fire back into these systems," said Brandon Collins, a forest science and wildfire expert at the University of California, Berkeley.

While the West was slow to adopt the practice, the region is now part of a nationwide movement led by some unlikely mentors, including Native Americans and tenders of the Southeast's remaining longleaf pine forests.

In January, the Forest Service set a historic goal of treating up to 50 million acres a year with mechanical thinning and prescribed fire.

"It's a drop in the bucket compared to the amount of work that needs to be done to protect our forests and grasslands," said Jeremy Bailey, fire training and network coordinator at The Nature Conservancy, a global environmental organization. "But we're starting to see some really wonderful examples of partnerships."

The reintroduction and expansion of such burns will require more staff, more training and new laws and liability requirements to protect those working to bring the land back to a natural and more resilient state, Bailey said.

He runs Prescribed Fire Training Exchanges, which each year gather hundreds of burners across the nation to meet for skill-sharing and practical lessons on how to use fire safely and effectively. Over time, they hope to build a prescribed fire workforce equal to the nation's 15,000-person fire suppression workforce.

There's a lot to be burned, or "treated," as the Forest Service likes to say.

"If we could get to point where we're treating a third or even half of the landscape ... then all of a sudden we have a pretty dramatic drop in these megafires," said Marc Meyer, an ecologist with the Forest Service who studies fire and post-fire restoration.

"It's not that they wouldn't occur, but we really would take a big bite out of the problem."

Whether fires are started by lightning or mindfully set by Indigenous peoples, scientists have shown most areas of the country historically burned as often as every two years to as seldom as every 25. The fires cleared away quick-burning shrubs, forest detritus and dead trees.

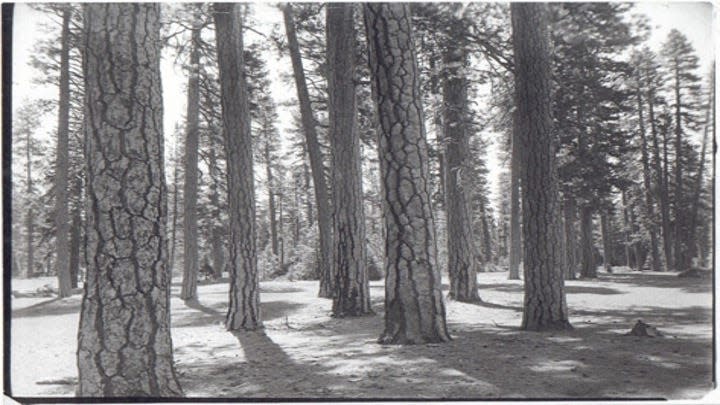

These frequent fires burned cooler, were harmless to fire-adapted trees, and left forests and rangeland healthier, Collins said. The low-intensity flames kept woodlands open, with widely spaced trees and open grasslands that burned quickly without being destroyed.

"By bringing fire back we're working with the local ecology," he said. "The forests you see today are uncharacteristically dense and full of dead plant material – fuel. That's not what they should look like."

Lessons from the past

On the other side of the continent, Florida doesn't spring to mind as a place with the know-how to save the nation's great western forests, but in many ways it is.

For most of its history, the Forest Service was staunchly anti-fire. Its goal was to preserve useful timber and stop what were believed to be abnormal and dangerous fires.

Beginning in the 1920s, the agency adopted a policy of total fire suppression. A 1935 decree required every fire be brought under control by 10 a.m. the day after it was discovered.

That memo never quite made it to Florida, said Morgan Varner, director of research at Tall Timbers, a Florida-based regional land trust and fire ecology center that has been burning its acreage since the 1920s.

"In the South, the fire culture in some ways never really left," he said. "Through burning, here we maintain the open pine savannah and woodlands that the early botanists who came through in the 1700s described."

A research hub for fire-dependent ecosystem management, Tall Timbers has trained hundreds of burn bosses, who have gone on to train others, spreading the gospel of safe, sustaining fire.

The center, perched in the Red Hills of Florida near the Georgia line, is "an epicenter of prescribed fire research," said Quinn-Davidson of the Northern California Prescribed Fire Council.

"The Southeast and Florida have this cultural continuity around prescribed fire that harks back to the early 1900s that was never broken," she said.

Another well of knowledge about how to safely use fire to cleanse and strengthen forests comes from the few Indian tribes that were able to keep their traditional knowledge.

When Europeans first arrived in North America, they found stands of open, park-like forests. They didn't realize that the landscape was formed by lightning strikes and millennia of burning by Indigenous people who used it to clear underbrush, drive prey, keep pastures clear and encourage the growth of useful plants, bushes and trees.

Bill Tripp, a member of the Karuk tribe near the California-Oregon border, practices what's known as "cultural burning," based on deep personal knowledge of a place. It's something that has been passed on in his family's oral tradition.

Tripp is the director of natural resources and environmental policy for the Karuk Tribe Department of Natural Resources.

He waits until the early sunny days of spring, when "the manzanita flowers will come out and bumblebees leave their nests under the black oaks." When the queen emerges, he knows it's safe to burn without harming her young.

The burns Tripp and others do are helping to restore the land's health and resilience.

"We're not at the scale we would like to be and need to be with fire, but at least we've held on to enough to bring it back the right way," he said from his home in Orleans, California.

Small burns, sometimes as little as a third of an acre, are something friends and families do together, part of a long cultural tradition of caring for the land, said Margo Robbin executive director of the Cultural Fire Management Council, which promotes burning on ancestral Yurok lands along the Klamath River in Northern California.

"In the last five years, people have started reaching out to native peoples to start learning what we know," she said.

That sense of community and place has taken root in the Great Plains. Farmers, ranchers and landowners realized over the past two decades how much they needed burning – though it didn't always come easily.

Mark Alberts reintroduced fire to his farm near Gothenburg, Nebraska, in 2000. His neighbors thought he had lost his mind.

“Mark was a four-letter word here for quite a while,” he said.

But when they saw his controlled burns killed off as many as 90% of the cedars encroaching on his rangeland, they started to come around to the idea. Today, the area is home to a robust grassroots community of burners, the Central Platte Rangeland Alliance, who come together to set fires on one another's land.

“It’s kind of like in the old days when people would get together to help their neighbors thresh or stack hay,” said Alberts, noting the care and expertise required.

“It takes 160 degrees to kill a cedar and 140 to melt skin," he said. "We’re trusting each other with our lives.”

Safety is paramount

Empowering local communities to play a role in prescribed fire land management is key, Quinn-Davidson said. She has helped bring Florida's cooperative model to the West, organizing burn associations and councils.

"People are sick of watching their towns burn up," she said. "The agencies don't move fast enough so these communities are starting to say, 'We're going to figure out how to do this ourselves.'"

On-the-ground training by mentors is essential to learn the techniques necessary to create safe, beneficial fire that won't burn out of control, experts say. That means watching the weather, paying attention to the wind and starting fires at the top of a slope so they burn slowly downhill, not rapidly uphill.

That's where having a large workforce focused on strengthening forests through burning would help, said Hurteau in New Mexico. Today it's something wildland firefighters do in their off-fire season. But the right time for prescribed burns is different in different parts of the county and often overlaps with fire season.

"Now is a perfect example," he said. "Things are bad here in the Southwest, but there are great burning opportunities in Northern California, Washington and Oregon, and there’s nobody capable because the Southwest is burning."

Escapes are rare – they happen in fewer than 1% of all such burns – but they carry the risk of turning the public against the practice, Quinn-Davidson said.

A three-month pause makes it seem as if decades of studies, science and observation were wrong, and today's management practices for controlled fire aren't good enough, she said.

Teams are already on the ground investigating what went wrong in the New Mexico burn, which will allow the entire burning community to learn from the mistakes and improve practices.

"But we can’t afford to stall this essential work," she said. "Blanket policies like this are not based on ecological reasons or even fire hazard; they are based on social and political considerations and the desire to have good optics with a skeptical public."

In Big Bear Lake, a popular tourist town less than 5 miles from last month's prescribed burn, residents welcomed the effort.

"The way I look at it, I'd rather have them do a prescribed burn to keep things safe," Kirk Ylinen said as he walked his dog at the forest's edge.

Weeks before the runaway New Mexico burn caused havoc, safety was top of mind for Crow, the San Bernardino Forest burn boss.

He spent the morning watching the first flames lick at pine cones, smelling the air as they inched across a 2-acre test plot and checking in with his weather observer.

"This is an art, not a science," he said, "though we do use a lot of science."

Crow followed the fire's progress, walking back and forth along the fire line, saying little but his head on a swivel. The wind picked up, stronger than forecast, and he watched as a young tree burst into flames with a sound like a thousand exploding matchboxes. The relative humidity had also dropped lower than had been forecast.

"It's too aggressive, too fast," he said, shaking his head. "The conditions aren't right. We could get too far into it and then the wind picks up more."

Tankers, fire engines and pickups lined the dirt road to the site. Months of planning and logistics were detailed in a burn book 2 inches thick. Firefighters had come from miles away.

But the wind was up, and Crow, who has spent 31 years fighting wildland fires, saw the fire closing in on the road that marked the boundary of the test plot. He had made his decision. The burn would go no further that day.

"I'm calling it," he said.

Contact Weise at eweise@ustoday.com

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: As wildfires threaten, prescribed burns can protect America's forests

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies