'I felt responsible': How women may process sexual assault by men they know

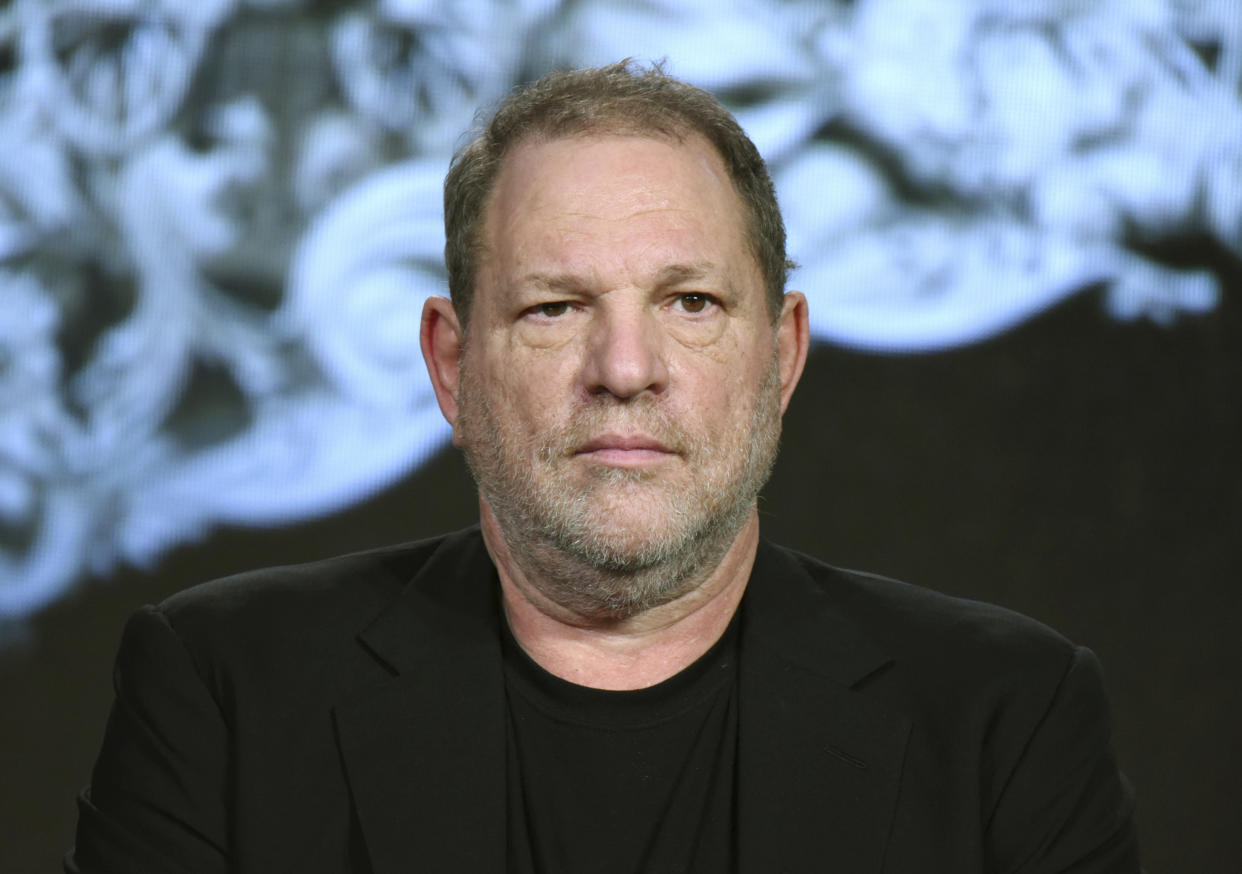

Among the 13 women quoted in the New Yorker’s explosive and damning exposé accusing mega-producer Harvey Weinstein of sexual harassment and assault is Italian director Asia Argento. Her story, in which she alleges in 1997 that Weinstein forcibly performed oral sex on her while she repeatedly told him to stop, is just one of the many accounts that are particularly graphic and harrowing. Still, Argento admits to continuing a relationship with him after the assault, including a consensual sexual one. “I felt I had to,” Argento told the New Yorker. “Because I had the movie coming out and I didn’t want to anger him.”

“The thing with being a victim is I felt responsible,” she said. “Because, if I were a strong woman, I would have kicked him in the balls and run away. But I didn’t. And so I felt responsible.”

Experts say that sexual assault, especially involving people who have a previous or ongoing relationship, is a particularly dubious crime to prosecute. Often the behavior or reaction of the victim may not meet society’s expectations, explained Mindy Mechanic, professor of psychology at California State University at Fullerton, who specializes trauma and sexual assault. “For example, almost no one would invite their carjacker or home invader over for dinner.”

But sexual assaults committed by someone who is known — whether the perpetrator is a co-worker, date, spouse or friend — is often processed in victims’ minds in a fundamentally different way. They are likely to second-guess the event or blame themselves for it, which contributes to feelings of intense violation of intimacy and trust. Rather than experiencing terror or fear, many victims will feel confused after the event, even denying it happened. That may be an effort to “preserve her faith in that individual who she likely has a history with, along with reinstating trust in her own ability to make good judgments about people,” said Mechanic.

“I’ve never encountered a sexual assault survivor who did not blame herself,” she added.

Self-blame offers a functional value to coping with abuse and violence — it allows her to restore a perception of control of the situation.

In the New Yorker exposé, Lucia Evans recounted a night in 2004 when she was led to meet with Weinstein alone in an office room full of exercise equipment. Evans said Weinstein forced her to perform oral sex on him. “I said, over and over, ‘I don’t want to do this, stop, don’t,’” she explained, but she ultimately gave up. Evans said she struggled for years with her memories of the incident: “It was always my fault for not stopping him,” she’d always think.

Tomi-Ann Roberts expressed a similar sentiment after she was met by Weinstein allegedly “in the bathtub” trying to persuade her “to get naked” in 1984. Roberts said she rebuffed his advances, but not before she apologized to him.

“I really thought that it was … my fault, that I was prudish or I was scared,” Roberts told ABC’s Juju Chang in an interview with “Nightline.”

Sexual assaults perpetrated by nonstrangers typically involve less violence than assaults by a stranger. The attacker often uses more nuanced tactics, such as verbal pressure, cajoling, manipulation or tacit threats. “These tactics add to the victim’s confusion about how to conceptualize or label the experience as a criminal act of rape or sexual assault,” said Mechanic. “It also contributes to self-blame and confusion.”

When outsiders blame the victim for sexual assault (“She was asking for it”; “Well, why was she there in the first place?”; “Why didn’t she tell someone?”), they are engaging in the same psychological process as the victim herself. “By telling ourselves we would never do what she did, we can reassure ourselves that we are powerful and invulnerable to victimization,” said Mechanic. “These are not truths, but rather self-serving cognitive distortions that have a self-protective function in the short run.”

Often, it takes others to help label a victim’s assault before she is actually able to label it as such. “This is why we’ve witnessed cases in the media in which many sexual assault or sexual harassment victims come forward only after one or several others have come forward,” said Mechanic. “There is power and bravery in numbers that is often absent in a single, vulnerable individual unable or unwilling to confer sexual assault allegations against a high-status, well-respected public figure.”

The Weinstein scandal prompted multiple male actors to come forward with their stories of sexual harassment, as well, and express solidarity with movie-mogul’s many alleged victims. In a series of tweets, Terry Crews explained that an unnamed Hollywood executive “groped” his “privates.”

Still, the actor admitted he didn’t come forward publicly:

I decided not 2 take it further becuz I didn’t want 2b ostracized— par 4 the course when the predator has power n influence. (9/cont.)

— terrycrews (@terrycrews) October 10, 2017

Several of the alleged female victims expressed being terrified that Weinstein could ruin their fledgling careers if they came forward. As temporary front-desk assistant Emily Nestor said of one of Weinstein’s alleged advances, “I was very afraid of him. And I knew how well connected he was. And how if I pissed him off then I could never have a career in that industry.”

“The unequal distribution of power and resources between the two individuals shapes the victims’ responses,” said Mechanic. “Perpetrators often knowingly choose victims of lower status and power as targets of sexual (or other) exploitation, precisely for these reasons — they realize the power and status they confer will likely shield them from allegations, while their victims are likely to be perceived as ‘sluts’ who might be trying to sleep their way to a better position. Power and gender matter.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies