How Far Would You Go To Disguise Your Privilege?

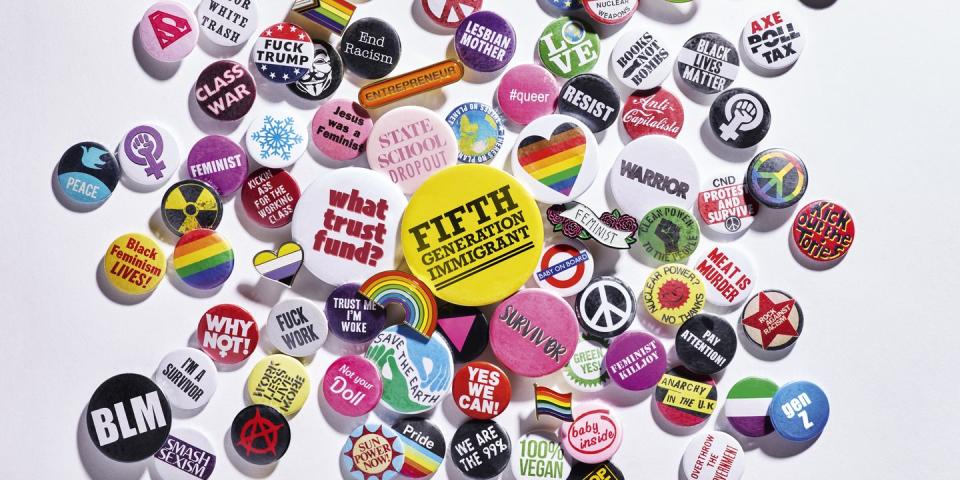

Is privilege a dirty word? If so, how far would you go to disguise yours? Modulate your accent, keep quiet about your parents’ jobs, talk about your years at state sixth form rather than the decade at private school... It’s innocent enough, but in these politically charged times, some people would rather take cover under a marginalised identity they’re not entitled to than face up to the advantages of their reality.

What is it that you need to make a success of any given career? A decent work ethic helps. Talent, too. Intelligence, application, charm, cunning – none of these go amiss. But let’s be real here. The main thing you need is luck.

'People really don’t like to hear success explained away as luck – especially successful people,' noted Michael Lewis, an extremely successful American journalist and author, in a famous speech on the subject given at Princeton University.

We all like to believe that we’ve got to where we are because of the shrewd choices we made, the hours of revision or the late nights put in at the office. But, more often than not, we have certain privileges to thank – being middle class, or white, or having supportive parents, or living near a good school, or having the right accent, or simply being in the right place at the right time. If you think about it, privilege is just luck stretching a long way back into the past.

I hope you don’t mind me being upfront about all this.

I just don’t think it’s possible to talk about class, privilege, identity or any of these excruciating topics if we’re not going to be honest. There’s one thing I’ve noticed working in the media – the same seems to be true in advertising, fashion, the arts, food, politics, tech… any career with a bit of prestige attached. And that is: despite the ludicrous amount of time we spend parsing each other’s accents for evidence of unearned advantage, or filling in online quizzes about how posh our living room is, very few of us are honest about our privilege.

And we tend to be dishonest in the same direction: most of us downplay, romanticise, deflect or under-emphasise the huge role that luck has played in even our modest successes. Sometimes we outright lie. Often, it’s to ourselves.

Back in January, Sam Friedman, a sociologist at LSE and board member of the Social Mobility Commission, published a study on just how widespread this tendency is. He had been struck by a finding in the British Social Attitudes Survey: 47% of people who work in middle-class professional and managerial jobs identify as working class, and even 24% of people whose fathers worked in middle-class jobs do the same.

In most countries, it’s the other way around: people in working-class jobs like to think of themselves as middle class. Friedman wanted to get to the bottom of this, so he listened carefully to the answers that actors, architects and TV professionals gave when he interviewed them.

‘When I asked them what class they considered themselves to be, instead of answering the question in a straight-up way, they would tell me a much more elaborate extended origin story that reached back to their grandparents and sometimes even further,’ he says. ‘And what they tended to emphasise was a fairly romantic story of working-class struggle and meritocratic striving.’

The interviewees weren’t lying, exactly, or pretending to be anything they weren’t. Some working-class people do end up rich, just as many ‘posh’ people are quite poor. But these ‘humble origins’ stories served a purpose. They allowed successful people to tell themselves that meritocracy worked, that they had faced barriers and struggled beyond them, that they had earned their success through talent and hard work.

It’s not hard to find other reasons why people from comfortable backgrounds are scrabbling around, trying to find some hard-luck story they can tell – some way in which they were disadvantaged or undervalued. These are fraught political times. Accusations fly. Cover is sought. From some quarters there is suddenly a perceived advantage in coming from a marginalised background.

In the US, we have seen the high-profile case of university professor Rachel Dolezal, who for many years adopted a Black identity and based a career around it, despite being born to two white parents. More recently, Jessica Krug, a professor of African and Latin American Studies at George Washington University, confessed to having pretended to be Black for years.

‘You should absolutely cancel me, and I absolutely cancel myself,’ she wrote in a lengthy blog post. Her students were unsympathetic. ‘For her to also play the victim in that self-flagellating way and say, “OK, cancel me, I’m a culture leech” – that kind of thing is exactly the problem with white allyship to begin with,’ wrote one.

Krug and Dolezal both earned money and gained opportunities by assuming identities that were not theirs to assume. In doing so, they undermined the Black experience, denying others opportunities in the process. But these are extreme examples. What usually happens is much more subtle – not identity fraud exactly, more like petty theft, white lies, misdirection.

I spoke to 39-year-old Allison, who works in advertising: ‘When I meet clients, I often lead with the fact I’m gay. It gives me a licence to speak more freely. While part of me cringes about being looked at as the single voice of “diversity” in the room, I’m also going to own that. Of course, I can’t speak for every marginalised identity, but if highlighting my sexuality over the fact that I’m really just another privileged white woman makes my opinion more valid, then I’d be an idiot not to capitalise on that. People used to call it “playing the gay card”, as if that’s a bad thing. These days, we all use our “diversity” to our advantage. Why shouldn’t we? It’s the thing that has held us back for decades, and now it’s giving us a leg up.’

But where do you draw the line between someone spotlighting one aspect of their life over another, as Allison did at her advertising agency, and the people wanting to be seen as somehow more interesting, their voice more ‘valid’, by appropriating an identity that is, let’s say, ‘embellished’?

In December, Hilaria Baldwin was vilified on social media for pretending to be Spanish when she definitely isn’t. Hilaria – otherwise known as ‘Hillary’, from Massachusetts – did something many of us get away with because we are not in the public eye. As Hadley Freeman put it in her column on the subject: ‘A lot of Americans give themselves dubious European roots. Seriously, have you ever been in New York on St Patrick’s Day? Has everyone forgotten Madonna’s English accent? We glam up our boring Americanness with some cosmopolitan European touches.’

Hilaria was, perhaps, just trying to appear more interesting. However, she inadvertently kicked a hornet’s nest, as many accused her of erasing the experiences of Latinxs, who are frequently marginalised in the US.

Friedman found that the tendency to be ‘inventive’ with one’s background story is more common in the creative industries, where the work is often uncertain and precarious. A loan from the bank of mum and dad, or a spare bedroom with a relative in London, or a godfather who happens to work for a TV company really help.

‘People either refrain from talking about this or don’t really think about it at all,’ Friedman says. ‘And because they work in fields that are competitive – usually with people who are still more privileged than themselves – they will often picture themselves as more hard done by than they actually are or, in some cases, appoint themselves as a spokesperson for the marginalised and oppressed.’

One of my friends who works in TV describes ‘a lovely colleague’ who parades around the office in streetwear and speaks with a thick London accent.

‘I just assumed she had a normal upbringing until I discovered her parents are like proper mad rich, live in a five-storey house in west London and don’t insure their Aston Martins because apparently the premiums don’t justify the cost.’ Her industry is full of such characters, she says. ‘Our diversity and inclusion meetings are mostly just posh people saying, “Yah, yah, things are unfair.” I have another colleague who wears quite tattered clothing, constantly talks about representation and how better the company could handle it, but lives rent-free in his parents’ multimillion-pound house in Hampstead.’

It’s all complicated by the fact that so much of the language around diversity and inclusion seems to require a university degree to understand it. The same friend worries that, for all the welcome efforts her company is making to hire a more racially diverse staff, every new employee is still a well-off female graduate.

‘I quietly worry that we’re changing the face of the company but not addressing underlying issues of [adherence to] social codes being what gets people jobs,’ she says. Paranoia is rife, particularly among colleagues who like to think of themselves as progressive. Many resort to the old playground bully tactic of accusing someone else of the very thing they fear being accused of themselves.

Amid all the subtle interplay of snobbery and inverse snobbery, people are defensive.

‘Some people like to announce they went to state schools like a badge of honour, definitely in an attempt to show you how much better they are for succeeding without all the private school “help”,’ complains one journalist who went to a fee-paying school. ‘Of course, it was a huge help, but equally I worked so hard.’ However, she is relieved to be spared the worst of it. She is from Manchester, so people from London tend to assume she’s working class.

You can see why someone might be wary of revealing any form of privilege – particularly in the hyper-judgemental world of social media. Earlier this year, model Chrissy Teigen committed what was widely seen as an unforgivable blunder on her Twitter account. She told her 13.6 million followers about the time she and her husband John Legend had been ‘upsold’ a bottle of wine in a restaurant, which turned out to cost $13,000 (£9,255).

The backlash was swift: ‘Now is not the time to be flexing how much money you and your out-of-touch husband have. People are dying, becoming homeless and starving,’ was one of the more printable comments. She had committed the sin of failing to be ‘relatable’. But what’s the alternative? That people who are obviously extremely successful and wealthy pretend not to be?

Candice Brathwaite, author of I Am Not Your Baby Mother, is living a slightly more modest version of that dilemma at the moment. She is a notable Black, working-class presence in the generally rather white, Breton-striped world of mummy influencers – and finds that this tends to draw out a stream of apologies and self-justifications.

‘Some people have this desperate need to prove their struggle, to prove their wokeness, to prove their awareness. It ends up being detrimental to any ideas of us engaging in a level conversation,’ she says. ‘Maybe [the person they’re talking to] doesn’t want to be reminded of the time they picked 1p coins out of the sofa to go and get something for dinner. Sometimes you just need to meet people where they’re at.’

And yet, Brathwaite says, she gets it. Her success has allowed her to move from one social class to another and it has left her conflicted.

‘I’m now in a certain circle where I have access to things that I didn’t used to, and I feel very guilty about that,’ she says. ‘I’m a working-class Black woman! I tick all of the boxes. I can fill that diversity quota. So it’s of no surprise to me that people who were born white middle class but have some ties to a working-class past feel the need to overstate just how hard their great-grandfather worked down the mine. I hate to say I get it, but I get it.’

Perhaps that’s a sign that you’ve made it: you have earned (or maybe just inherited) the right to feel guilty.

‘Yeah, but you know where that energy could be better spent?’ says Brathwaite. ‘Think about how you can lift people up. Who can you get in the room? Who can you put forward for a job who might have been overlooked? Who can you mentor? So much of the work isn’t going to be on social media. It’s not going to be the stuff that you’ll get a pat on the back for.’

The best thing you can do with all that luck isn’t pretending it doesn’t exist – it’s using it to help the unlucky.

For Sharmaine Lovegrove, founder of Dialogue Books, the conversation around class simply takes up too much oxygen.

‘The problem is, if everybody feels sorry for themselves, they’re not able to see what stops some people from having opportunities as opposed to others,’ she says. ‘That’s one of the reasons why the vast majority of industries such as publishing are white female. If you all think you’ve been victimised by a system that’s actually working in your favour, then you aren’t able to bring anyone else up. It doesn’t allow for the empowerment that comes with being comfortable. I’m only able to do my job because I’m comfortable – in who I am, in my family life. I’m not worried about paying my bills.’

But what about people who appear to tick all the privileged boxes, but aren’t comfortable with it? Contemporary society is making us all hyper-suspicious of one another. Wealth is concentrated among an elite group who deflect their advantage by emphasising how hard they’ve worked to get it – and, in some extreme instances, take cover under a more marginalised identity than they are entitled to. Is it any wonder people are feeling embattled and insecure?

‘Black people and working-class people aren’t afraid of the future in the same way as a lot of middle-class people are,’ counters Lovegrove. ‘They’ve always had to hustle. Working-class people have always had to do the work. White middle-class liberals are realising they’re not equipped to deal with a world that functions in any way that’s different from what they’re used to. That’s the problem. Of course you’re scared now! But you’re scared because of your privilege. If you’ve ever had to hustle, you’re like, Bring it on. It’s just another hustle.’

Perhaps this is the future. But if it’s going to be any brighter than the present, I reckon it would be good to begin by acknowledging one another as the strange, complex, contradictory beings we all are. We love putting one another in boxes. We hate being put in boxes ourselves. Maybe we should stop doing it so much.

This article appears in the June 2021 issue of ELLE UK.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox.

In need of more inspiration, thoughtful journalism and at-home beauty tips? Subscribe to ELLE's print magazine today! SUBSCRIBE HERE

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies