This family fled Mexico and sought asylum through an app. Not everyone is so lucky

NOGALES, SONORA — The air was frigid and silent.

A woman from Michoacán, Mexico, huddled with her three sons on a recent morning as they stood outside the Dennis DeConcini Port of Entry in Nogales, Sonora. The family stood together, swaddled in winter coats and baseball caps as they clutched their backpacks and a handful of luggage.

In the dark early morning hours, the family was illuminated only by the fluorescent lights emanating from beyond the revolving metal gates in the crossing facility.

A few scattered people strolled through the gates into Mexico, passing the family and a white plastic table where steaming tamales were being sold.

After nearly five months of being stranded in Nogales, the family was minutes away from the opportunity to request asylum in the United States. The family fled from their home after members of organized crime killed the woman’s husband and attempted to kidnap one of her sons.

“We only came here fighting to ensure the lives of our loved ones and that is, more than anything, what moves you to request asylum,” the woman said.

As more and more international travelers walked by, the family waited. Their appointment with U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials was still 15 minutes away.

The family was one of the first to schedule an appointment through the new processes of the CBP One app, a mobile government application that can now be used to book appointments to seek a humanitarian exemption from Title 42, the pandemic-era restriction that has allowed border officials to rapidly expel migrants arriving at the country’s borders for nearly three years.

Policy announcement: Biden expands Title 42 under new rules; app required to claim asylum at border

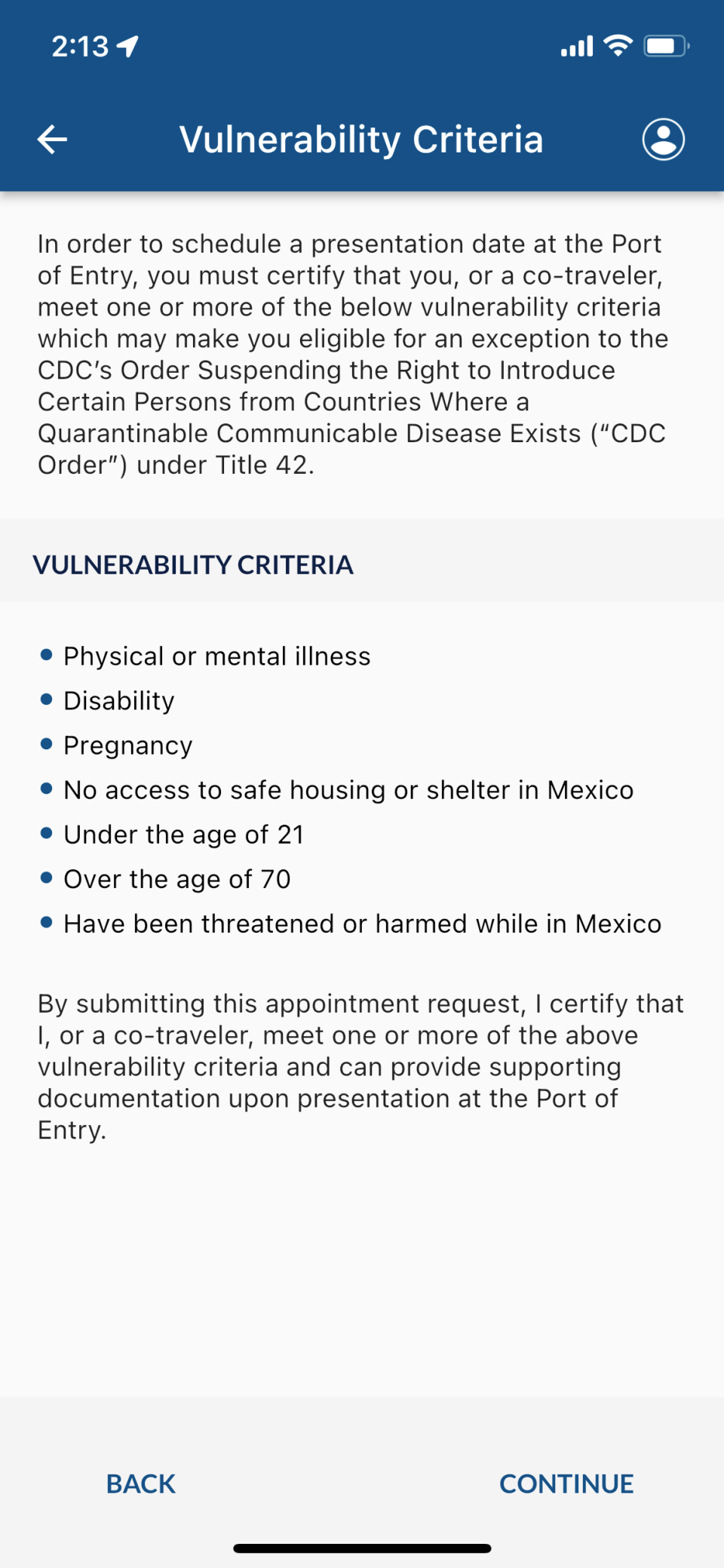

While Title 42 remains in place, asylum seekers can request an exemption from the policy if they meet certain vulnerability criteria. The criteria to request an exemption are as follows: physical or mental illness, disability, pregnancy, no access to safe housing or shelter in Mexico, under the age of 21, over the age of 70, or have been threatened or harmed while in Mexico.

The free app has been characterized by CBP officials as a new streamlined way to request an exemption from Title 42 while reducing crowding and wait times at certain ports of entry. Asylum seekers previously were required to have the help of a lawyer or a nongovernmental organization to request an exemption.

The new function allows asylum seekers to request an exemption individually, facilitating the process, officials say.

Still, the new process has drawn mixed reactions from immigration advocates who say the app could lead to disparities in who is able to book an appointment. Advocates already have begun to report a slew of issues with the application in the first few weeks after the process was implemented on Jan. 12.

With a few minutes until their 7 a.m. slot, the family began to say their goodbyes to family members and local advocates who had accompanied and helped them during their time in the border community. Then, they picked up their luggage and pulled their backpacks on, bracing for whatever lay ahead beyond the metal gates.

The woman, who asked not to be identified for fear of retribution from organized crime elements, said a blend of happiness, fear and nervousness swirled inside her as she waited for her appointment to possibly be paroled into the U.S.

Mostly, she said she felt happy.

“You go into the unknown again, but now you go knowing that you are going to put your children in something safe,” the woman said. “I don’t want to be afraid anymore.”

As the family pushed through the metal bars of the revolving gate, the sun began to rise, announcing the start of a new day.

What is CBP One?

President Joe Biden announced the new app process, alongside a slate of humanitarian parole programs for certain nationalities, in a Jan. 5 speech. The new app feature allows migrants to schedule an appointment with CBP officials as they’re traveling toward the U.S.-Mexico border to seek asylum.

The scheduling feature becomes available anywhere north of the 19th parallel, which is slightly south of Mexico City, according to Bonnie Arellano, supervisory program manager for admissibility for CBP’s Tucson field office.

Migrant encounters: Migrants from many countries are arriving at the US-Mexico border. Here's why

Users can submit biographic information such as names, dates of birth and a live photo through a mobile device prior to their appointment in order to facilitate the process.

The DeConcini port of entry in Nogales is the only port where the scheduling feature is available in Arizona and one of eight ports where it is available along the U.S.-Mexico border. Appointments started Jan. 18 with new appointment slots released daily up to 14 days in advance, CBP said.

“This gives (asylum seekers) an opportunity to get to the port in a timely fashion, know that they'll be able to be received at a certain time and get the opportunity to tell their story,” Arellano said.

“Having a mom with three kids stand outside the port for several hours waiting to come in as compared to getting an appointment and coming in through CBP One are two very different stories for that person.”

In Arizona, an average of 60 new appointment slots are released daily with 30 appointments in the morning and 30 in the afternoon, Arellano said. In the days since the rollout of the feature, however, migrant advocates in Nogales, Sonora, have reported that the number is closer to 40 available slots each day.

“It takes care of a lot of those issues that a lot of places and a lot of people have been exploited and I believe that this is a very good opportunity to smooth that process out,” Arellano said.

When Title 42 lifts, asylum seekers can use the feature to schedule an appointment at a port of entry to request asylum, according to CBP.

Concerns, problems arise as new government app feature rolls out

Asylum seekers wake up at around 5 a.m. every day at the Casa de la Misericordia y de Todas las Naciones, a migrant shelter that caters specifically to asylum-seeking families and single mothers in Nogales, Sonora.

People rise at that time in order to start filling out their application for when a new day of appointment slots opens on the CBP One app at 7 a.m. Oftentimes, asylum seekers will fill out the required information by hand on paper forms provided to them by the shelter prior to transferring the information into the app.

At around 10 on a recent morning, residents of the shelter were in a solemn mood. The majority of people had not managed to book an appointment on the app.

Only five people at the shelter that morning were able to book a time slot.

Among them, a father and daughter booked an appointment within the minutes allotted to complete the process. The mother, however, was not able to get an appointment in time.

She hoped to get a slot the next day in order to be able to catch up with her family in the U.S. when their appointments went through.

Christmas refuge: Days before Christmas, migrants fleeing poverty and danger find shelter at a Mesa church

Migrant advocates have raised concerns about the rollout of the new feature in the app in the weeks since it was implemented, citing technical and logistical setbacks for applicants. The feature also could lead to disparities among who is able to book an appointment, advocates say.

An applicant’s ability to snag an appointment is largely dependent on technological literacy, internet access and proficiency in either English or Spanish. These facets of the feature could leave many asylum seekers at a disadvantage, according to Chelsea Sachau, managing attorney of the Border Action Team at the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project.

“While we are always in support of creating safe, orderly, lawful processing, (the Biden administration) is really doing it in a way that is going to privilege a few who are already likely to be more stable,” Sachau said.

“It's going to leave the most vulnerable out in the cold, affected and returned to danger.”

The app requires people to create a profile that requires email addresses, passwords and, sometimes, phone numbers to book an appointment. This can be challenging for many asylum seekers who must often create email addresses and obtain phone numbers from scratch.

Applicants have reported that, sometimes, they’ll be kicked out of the app near the end of the process and have to start the application all over. By that time, all of the daily slots will have been filled.

The feature also is only available in English and Spanish, which excludes a large portion of vulnerable asylum seekers who aren’t fluent in those languages. There have been conversations about making the feature available in Haitian Creole, one of the official languages of Haiti, Arellano said.

For subscribers:Migrants are arriving at the US-Mexico border from many countries. Here's why

“There are serious concerns about accessibility,” said Alex Miller, director of the Immigration Justice Campaign at the American Immigration Council. “Whether you have access to the technology, whether you are literate, whether you have a smartphone, competency in that technology, and whether you have support to triage those issues you encounter.”

Advocates have raised concerns about the feature being exclusively available at one port of entry in Nogales. This availability could force asylum seekers in other border communities, such as Agua Prieta and San Luis Río Colorado, to go to Nogales in order to request asylum through the app.

“It's only going to be accessible at certain points of entry, which means if you are an asylum seeker not near one of those ports, you will be forced to travel potentially hundreds of miles through dangerous cartel-controlled territory,” Sachau said.

The Florence Project has helped more than 250 applicants book appointments through the app. As time passes, it has become more difficult for asylum seekers who have been waiting in Nogales to book an appointment because more and more people are using the app on their way to the border, advocates say.

There have been reports of people charging applicants to fill out the form for them when the feature is actually free to use. Advocates have cautioned asylum seekers against paying anyone to fill out their application as it can lead to their vital information being stolen and possibly sold.

What happened next to the family?

The woman and her children now found themselves sitting around a table in a welcome center run by Casa Alitas, a Tucson-based migrant aid program, in Nogales, Arizona, roughly four hours after they first crossed the metal threshold.

The woman concealed a smile and a chuckle beneath a blue face mask when asked about how she felt to have been admitted into the country.

She held her hands over a collection of papers that were encased in a clear plastic sleeve. The papers included each family member’s I-94 form, a CBP-issued arrival/departure record, and information about their upcoming court date to begin their asylum proceedings before a judge.

The family’s court date is in late March, leaving them about two months to settle down and find a lawyer to take their case. Even though the family found refuge in the U.S., a multitude of obstacles remains in their path.

About 17 other asylum seekers sat at tables nearby as a staff member gave a brief orientation on what their next steps would be.

The people in the center had appointments through CBP One and were paroled into the country. A few others in the original group had been denied entry during the screening process and remained in Mexico, the woman said.

A bus would soon arrive and take everyone from the center to Tucson, roughly an hour away.

There, passengers could travel to their final destinations in the country via pre-arranged and paid travel plans that they coordinated with their sponsor or relatives while waiting at the center. The woman and her family planned to take the bus to Tucson where relatives would be waiting to take them to Phoenix, their final destination.

The sun now shined brightly, baking the streets of Nogales as the community rumbled to life. Cars lined up to pass into Mexico as a trio of men nearby advertised shuttle and bus transportation to Tucson and Phoenix to walking passersby.

The bus soon arrived and the family boarded, concluding a five-month-long chapter in their journey as they embarked on a new one toward the unknown.

Have a news tip or story idea about the border and its communities? Contact the reporter at josecastaneda@arizonarepublic.com or connect with him on Twitter @joseicastaneda.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: CBP One app worked for this family. Others raise concerns

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies