Fame at last for Japanese explorer who almost reached the South Pole

Summer in the southern hemisphere approaches and with it the 110th anniversary of one of the most compelling contests our planet has ever witnessed. For two men it would ensure they passed into legend. Norwegian Roald Amundsen’s legacy was secured when he became the first person to reach the South Pole on 14 December 2011. His rival possibly achieved even greater fame dying in the attempt. Briton Robert Falcon Scott arrived on 17 January 2012, 34 days after Amundsen, and perished on the return journey. Their race to the pole has inspired books and movies, and they are immortalised in the scientific base at the pole which bears their monikers.

But they had a competitor, a man whose name lacks the resonance of his more illustrious contemporaries, but one who is now rising to prominence outside his homeland as his story is being rediscovered. The invisible third man was as keen as his rivals to book his place in history, but in his country there was little appetite for the challenge he was undertaking. In fact he was considered idiosyncratic and, ironically, unpatriotic.

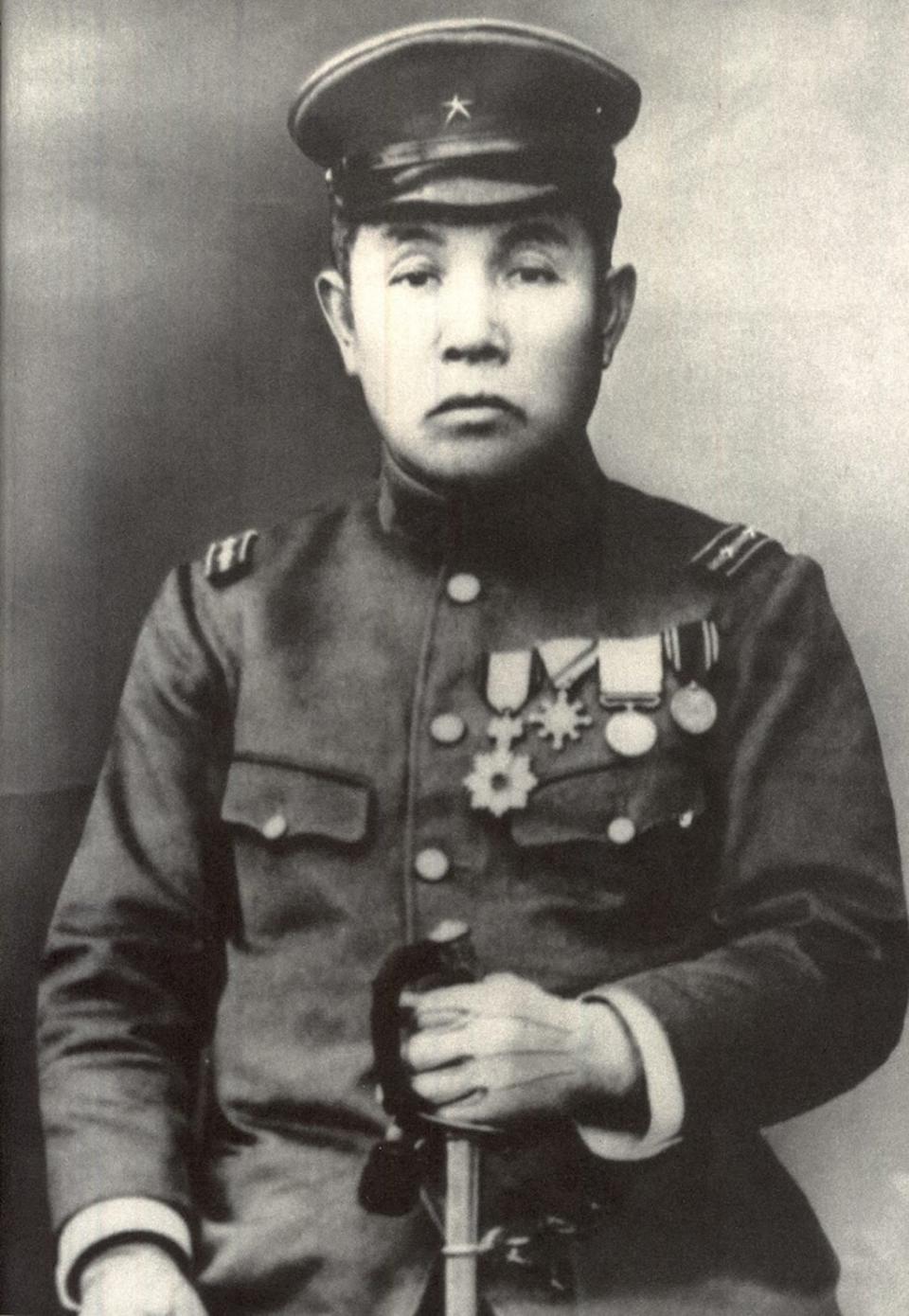

Nobu Shirase was born in Konoura (now Nikaho), Japan, in 1861. At that time Japan’s ruling dynasty, the Tokugawa shogunate, forbade any person to leave the fatherland. If you attempted to do so and were caught, you would be executed. When the shogunate was overthrown in 1868 following the Boshin civil war and Japan slowly began to modernise under the Meiji dynasty, the law was rescinded but still very few Japanese chose to leave their nation. Shirase was the exception.

After he had served with the military in the Alaskan Arctic in 1893 he developed his enduring passion for polar exploration and research. Later he was part of a team on covert military operations on the Kuril Islands, the territory of which Japan has for centuries disputed with Russia. His ill-equipped party suffered extreme privation, enduring two scurvy-ridden winters on the islands before being relieved in 1895. Nineteen men died and he was one of only two officers to survive, but his fervour only grew. He wanted to conquer the conditions and bring glory to his nation.

The only problem was, his nation had no interest. Outside Japan, the race to the planet’s poles was already engrossing an eager public, encouraged by the more patriotic sections of each country’s press. As the age of colonialism was coming to an ignominious end, it was instead being fought by proxy, national achievements replacing hegemonic conquest. It was imperialism by other means. But not in Japan.

Initially, Shirase was set on becoming the first man to the north pole but when Americans Robert Peary and Frederick Cook claimed – contentiously it transpired – to have reached it in 1909, focus shifted to Antarctica. In January 1910 Shirase laid out his plans before Japan’s Imperial Diet. He promised to raise the Japanese flag at the south pole within three years. The bureaucrats were unimpressed. The concept of geographical exploration was totally alien to them. They simply couldn’t see the point.

Undaunted, Shirase set about his preparations. Since his time in Alaska he had already deliberately adopted a lifestyle of deprivation, planning for life in the frozen wilderness. He refused to heat his home and eschewed hot food and drinks, alcohol and tobacco. His biggest challenges, however, were time and money. Realising the government wouldn’t fund him Shirase began to sell his mission to the public as a scientific one, similar to Scott’s fundraising drive in Britain.

Was Shirase a real explorer or, following Japan’s recent victories in wars against China and Russia, looking for a new conquest? Or at least new fishing waters?

His journey would not, he insisted, be for the sake of polar primacy but instead would explore the continent, its geology, its fossils, its fauna, its meteorology. However, whatever impression he may have been giving to the Japanese public, the pole remained his goal.

Although the Japanese press continued to ridicule him, pointing out that the likes of Albert Einstein didn’t collect rocks and measure the wind, he piqued the interest of former prime minister Shigenobu Okuma who, along with small donations from students, bankrolled Shirase’s mission just when it seemed likely he would be left empty-handed. It was barely enough, yet it would have to do.

But by now Shirase was running late. Both Amundsen and Scott had set sail for the southern continent in the middle of 1910. Shirase’s converted fishing vessel, the Kainan Maru (Japanese for “Southern Pioneer”), and its crew of 27 did not depart Tokyo until 29 November. Waved off by just a handful of his student donors, he was more than three months behind Amundsen. It would make all the difference.

In January 1911 Amundsen set up base on Antarctica at the Bay of Whales. The same month Scott arrived at Cape Evans. They both intended to stay throughout the Antarctic winter, studying the continent, and march for the pole the following summer, departing as soon as conditions would allow sometime around mid-October (in the end Scott’s team couldn’t depart until November giving Amundsen a head start).

Shirase intended to do the same but his initial delay plus dreadful weather conditions en route meant he arrived far too late, in March 1911. Scott’s ship Terra Nova and Amundsen’s Fram had already left for the safety of New Zealand and would not return until the following spring with supplies for the men left behind. By March the sea was already freezing and it was impossible for Shirase to land, as storms pounded the ship and coastline. The ship risked being trapped and crushed in the ice, indeed more than once it took expert seamanship by the captain to break free of the solidifying ocean. “We saw only icebergs, snow and penguins,” the chief officer later reported.

Frustrated, Shirase had to return to Sydney to sit out the winter. News had already reached Australia from New Zealand where Shirase had docked before heading to Antarctica that his ship, indeed his entire expedition, was poorly equipped and under-prepared.

Compared to his rivals’ ships, Kainan Maru was tiny, a schooner with three masts, and its engine notably underpowered. The New Zealand newspapers had reported that Shirase’s sledges were made of flimsy bamboo, his maps and charts cursory and his provisions – squid and beans, rice and pickles, dried fish and bean curd – lacked the calories that were believed necessary to fuel men to the pole and back. Amundsen and Scott instead relied on copious supplies of pemmican – dried, powdered meat mixed with fat and berries. “By contemporary standards the expedition was inadequately equipped,” says Robert Headland, a senior associate specialising in historical polar geography at the University of Cambridge’s Scott Polar Research Institute. “Their food was notably unsatisfactory but, serendipitously, because they did not overwinter in Antarctica they did not require the supplies that Scott and Amundsen needed.”

In his logs Shirase wrote that The New Zealand Times had commented disdainfully “that we were a crew of gorillas sailing about in a miserable whaler, and that the polar regions were no place for such beasts of the forest as we. The zoological classification of us was perhaps to be taken figuratively, but many islanders interpreted it literally, because crowds of people came to our tents daily to observe the 'sporty gorillas' misguided with the crazy notion of conquering the South Pole.”

The Australians too were suspicious. Was Shirase a real explorer or, following Japan’s recent victories in wars against China and Russia, looking for a new conquest? Or at least new fishing waters? Certainly many Australians were hostile to the crew’s presence. “Anti-Japanese sentiment was running high in both Europe and Australia,” says Headland. “The nation was militarising, and outsiders knew nothing of Japan. It’s fair to say that the only experience most westerners had of life in Japan was seeing Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera The Mikado, first performed in 1885.” With such limited knowledge of the culture, it’s perhaps little wonder Shirase and his men were treated as interlopers in Sydney.

Fearful of disembarking and with little money or food, the crew lived as virtual recluses until the Australian geologist and polar researcher Tannatt Edgeworth David of the University of Sydney made a point of supporting Shirase in the Australian press. Eventually the crew was able to erect huts on land offered by David and leave the prison-like confines of their ship. Shirase showed his gratitude by giving David his samurai sword – it is now in the Australian Museum.

Despite the borderline racism and increasing scepticism, Shirase declared that he would return to Antarctica in the spring, departing for the pole in mid-September and returning in late February after a return journey of more than 870 miles. But as his provisions were consumed, the dogs he had brought to haul his sledges died and the weather for departure refused to turn favourable, Shirase’s dream began to wane.

He told The Sydney Morning Herald that he was changing his plans. His mission would be purely scientific with no attempt on the pole. He sailed south again on 19 November arriving at Antarctica near the Admiralty Mountains in early January 1912, the height of the Antarctic summer. Weather was good and the Kianan Maru sailed across the Ross Sea passing close to Amundsen’s winter base, even spying Fram awaiting his return from the pole (and confirming to Shirase that his dream would never be realised), before putting into land near the Ross Ice Shelf, the first Japanese to set foot on the southern continent.

Yet the pull of the pole was too much for Shirase. It was a millstone and a magnet… so near but yet so far. He had insisted his team would confine themselves to scientific research but the weather was good, and he had dreamed of the opportunity for so long. Modern sensibilities might forgive him the indulgence, but he suspected the government and public back home might not. Nonetheless, he decided to march south. He reckoned he had 20 days supplies and he intended to see just how far he could get. Picking four key men, each pulling one of the “flimsy” bamboo sledges, and taking the remaining dogs he launched what he termed a “dash patrol”. His party included Terutaro Takeda, his lead scientist, and the crew’s best sled dog handlers. “For summer in the Antarctic his equipment would have sufficed,” says Headland. “His men were from Ainu stock, familiar with severe winters in Japan, and his dogs and sleeping bags could all cope with summer conditions.”

But with typical misfortune, the weather turned (as Scott would also discover to his peril). They toiled through blizzard after blizzard before taking to their tent to sit out the storm. They suffered frostbite, more of the dogs perished and on 28 January Shirase decided there was no other choice but to turn for home. Takeda put them at 80 degrees 5 minutes south, more than 150 miles from their base on the coast. They raised the Japanese flag, saluted, buried a copper box with details of their journey and set off back. On 3 February, only 18 days after their arrival, they were sailing for Tokyo.

Despite his travails on his long journey south for little reward, it is arguable that the most challenging part of Shirase’s story was yet to come. Surprisingly at first, when he arrived in Tokyo in June, he was treated like a hero. His student backers had lauded his efforts and public opinion had shifted somewhat. But then news came through that he had been beaten to the pole by Amundsen, that his mission had started late, been poorly equipped and badly planned, and that he had stayed only briefly in Antarctica. Interest waned.

Shirase was the first non-European to explore any part of Antarctica. He travelled as far south as any other humans at that time, bar his two rivals and Anglo-Irish explorer Ernest Shackleton

Shirase knew his fate before he arrived back, having written presciently of it in his logs. Japan in the early part of the 20th century was a society that saw failure equated with shame. Couple that with a mission that was always deemed folly by officialdom and a sense, upon his return, of “we told you so” meant Shirase would live out his life bereft of the fame his achievements perhaps deserved.

He knew full well if the government that now disowned him had offered to fund his mission, he could have arrived in Antarctica at the same time as Amundsen and Scott thus giving him a far better chance of success. But the public cared little for any excuses, however legitimate. He seemed destined to always be eclipsed by the two Europeans. Even his professed concentration on the science yielded few results of note, and Takeda’s scientific credentials were later discredited, heaping more discomfiture on the unfortunate Shirase. There was no room in the polar race narrative for the man who couldn’t even come third.

Perhaps worse, his one-time sponsor, Okuma, shunned him and would no longer settle his bills. The expedition had racked up huge debts. His memoir, written in 1913, did not sell in the numbers he hoped for, nor did film footage of the mission. He could no longer afford his home and would live out the remaining 34 years of his life with his wife Yasu in relative obscurity, dying aged 85 in 1946 in a flat above a fish shop in Toyota.

Initially, his mission had attracted even less attention outside Japan. But in 1933 the first brief English language account of his journey was published in The Geographical Journal and belatedly, when the Japanese Polar Research Institute was founded in that same year, he was made honorary president. By the time he died he had settled his debts. And, since his death, very slowly his nation and the wider polar research community have begun to rehabilitate Shirase. He might not have reached the pole, and the science he hoped to conduct might have been diminished by his choice of chief scientist, but to be fair Amundsen too – unlike Scott – produced nothing in the way of scientific benefit. Naomi Boneham, archives manager at the Scott Polar Research Institute, points out that it wasn’t until just 10 years ago that his memoir detailing the full account of his expedition was translated into English by Lara Dagnell and Hilary Shibata. “Western readership was almost non-existent to this point,” she says.

Shirase was the first non-European to explore any part of Antarctica. He travelled as far south as any other humans at that time, bar his two rivals and Anglo-Irish explorer Ernest Shackleton. He also travelled further east along the Antarctic coast than anybody before him. He had a fraction of the budget of his rivals, a ship half their size, and unlike them it was his first trip to polar climes yet, crucially, none of his team died. And, although he might have been scorned for his “toy-like” bamboo sledges, their light weight proved to be a boon. When he turned for home after his trek south, he covered the 150 miles in an incredible three days, far faster than Amundsen with his trained dog teams had managed. “They turned out to be faster than wood and metal sledges – although possibly not as sturdy over difficult terrain,” says Headland.

It took a long time, way too long, but Shirase has begun to receive the recognition he perhaps deserves, shifting in the annals of Antarctic exploration from risible footnote to acknowledged pioneer. “Shirase was somewhat eccentric, but he did not lack enthusiasm and, as far as was possible in Japan, he researched Antarctica before his mission. Effectively, in the end, he was a victim of circumstances, as were many expeditions to Antarctica, a totally unknown continent, at that time,” explains Headland. “Maybe an assault on the pole was never practical. He would have encountered glaciers and mountain ranges inland on his chosen route and would probably have had to abandon the attempt. But nonetheless his reputation has been rehabilitated. He is considered a serious pioneer of the Heroic Age of Antarctica.”

The explorer would, no doubt, be gratified to learn that Japan’s Antarctic research ship is called the Shirase and that geographical features on the continent are named after him, including the eastern coastline that he was the first to explore. Perhaps, more fittingly, his home town Nikaho has a statue and a museum celebrating his life and his expedition.

Every year, on 28 January, the day Shirase reached his furthest point south, the museum holds Shirase’s Walk in the Snow, a tribute to the army lieutenant who became Japan’s first polar explorer. A man no longer considered merely an annotation in polar history.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies