Everything you wanted to know about the culture wars – but were afraid to ask

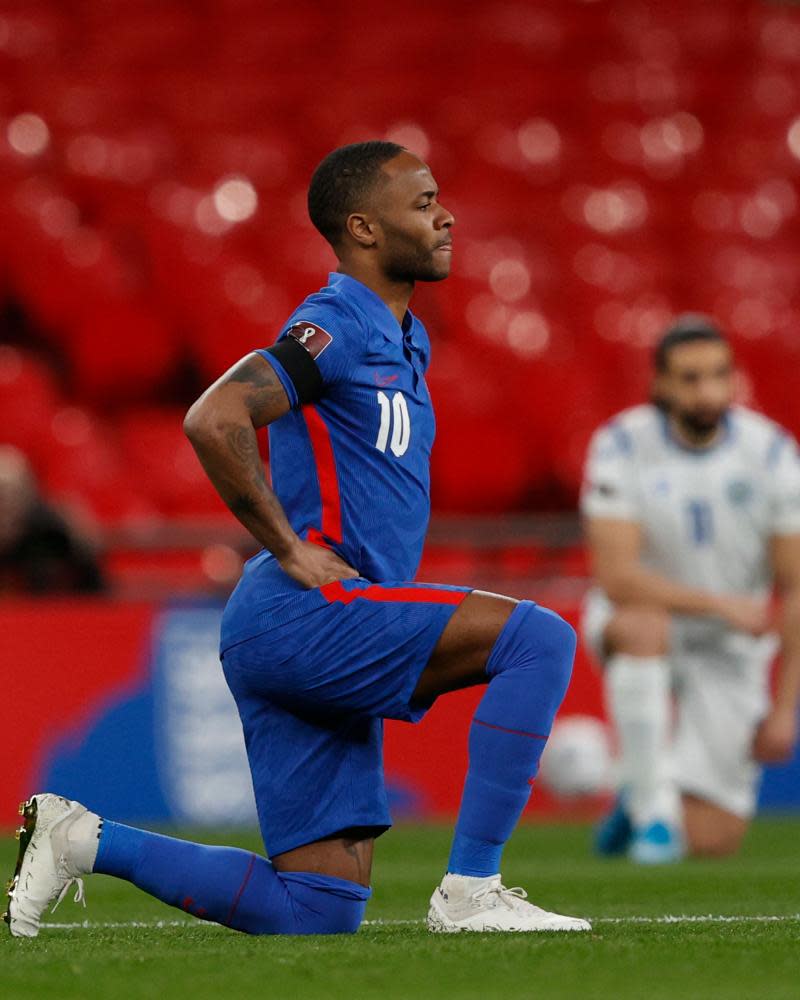

Last week produced an eventful but not untypical weather-front of news stories about culturally contentious issues. There was the microstorm about the Queen’s photo being taken down in the common room at Magdalen College, Oxford; the tiny tempest of Test cricketer Ollie Robinson being dropped for racist tweets dating from when he was a teenager; the squall over the England football team’s commitment to taking the knee; and the sudden shower of Oxford academics boycotting Oriel College over its decision to retain its reviled Cecil Rhodes statue.

These, along with the deathless headline “Law student cleared after saying women have vaginas”, were examples of what might also be called skirmishes in a larger and ongoing series of battles: the culture wars.

As a recent report by the Policy Institute at King’s College London shows, there has been an exponential rise in the past couple of years of news stories that use the term “culture wars”. Exactly what constitutes a culture war is just one of the many issues that people fight about in the culture wars, and there’s a sizeable minority of participants who go so far as to argue that the main characteristic of this present culture war is that it’s not really a culture war.

According to the Policy Institute, a quarter of the articles it analysed took the position that “culture wars are either overblown or manufactured – if they exist at all”. If that’s just the media being contrary, then take a look at the public at large. In a Times Radio poll conducted in February, respondents were asked “When politicians talk about a ‘culture war’, what do you think they mean?” Only 7% came up with a relevant answer, 15% got it wrong, and a slightly concerning 76% said they didn’t know.

Just because people don’t know what a culture war is doesn’t mean they’re not in one. For, as all those feverish headlines suggest, there does appear to be something afoot.

“I do think we’re in a culture war,” says Matthew d’Ancona, an editor at Tortoise Media, where he has written perceptively about the politicisation of culture. “There have always been cultural conflicts but it’s become much sharper in the last 20 years thanks to declining trust in institutions that were meant to hold together the cohesion of society, some of the growing inequalities, and most of all the proliferation of technology that enables and indeed encourages people to cluster in their cultural groups.”

The historian Dominic Sandbrook agrees that a culture war is under way but cautions against overstating its dimensions. “I think one of the mistakes people make when they talk about culture wars is they think that it’s something that necessarily sweeps up the whole of society, and everybody’s invested in it.” He thinks that more often than not it’s a dispute between two sides of an educated elite.

What does seem clear is that symbolic issues and questions of identity occupy a larger and more antagonistic position in the general culture than they did 10 or 20 years ago. As d’Ancona suggests, this development and the explosion in social media, where millions of people can seek out like-minded opinion-holders, are unlikely to be coincidental.

Just as significantly, confidence in the traditional concerns of politics – political parties, economics and wealth redistribution – has taken a bit of a battering. Bill Clinton’s campaign strategist James Carville famously said “It’s the economy, stupid” to explain what made the difference between electoral victory and defeat.

While that’s still a vital factor, the financial meltdown and the bailout of banks in 2008 left many voters baffled as to what was going on.

As old-style political parties struggled to articulate what needed to be done, the opportunity was there for populist politicians and narratives to fill the comprehension void.

For the simple truth is that while it’s not easy to express an informed opinion about the effect of collateralised debt obligations on the American housing market, it doesn’t take a doctorate to decide whether a statue should be pulled down, or to work up an unbending judgment about the character of the Duchess of Sussex. As Sandbrook puts it: “People are more interested in flags than inflation.”

If public focus has shifted towards more symbolic and emotive issues, then it’s a change that can be both exploited and directed by the cynically astute.

“There have always been stories like the one about Magdalen College and the image of the Queen,” says d’Ancona.

“What’s interesting now is the speed with which cabinet ministers or indeed No 10 respond. That to me signals we’re into a different kind of political game. One where a strategy is at work.”

He points out that the combined effect of Brexit, the pandemic and the government’s commitment to a levelling-up agenda means there is an extremely challenging period ahead in terms of policy and its implementation. “Everything the government has on its to-do list is hard.”

It’s a human instinct and practically a political rule that when confronted with a number of tough priorities, the first job is to hunt around for easier options. “The culture wars suit the Johnson way of doing things,” says d’Ancona. “He’s good at things that involve short, memorable slogans and showmanship. Is he good at test and trace? Not conspicuously so. Is he good at PPE? No. Is he good at lockdown timing? Absolutely not. But the thing that he’s quite good at is spotting a dividing line.”

Sandbrook is less inclined to see debates about national and personal identity in terms of political distraction. He thinks they plug into deep-rooted and timeless matters of belonging and place. Along with his fellow historian Tom Holland, he co-presents a podcast, The Rest Is History, which recently looked at the history of culture wars.

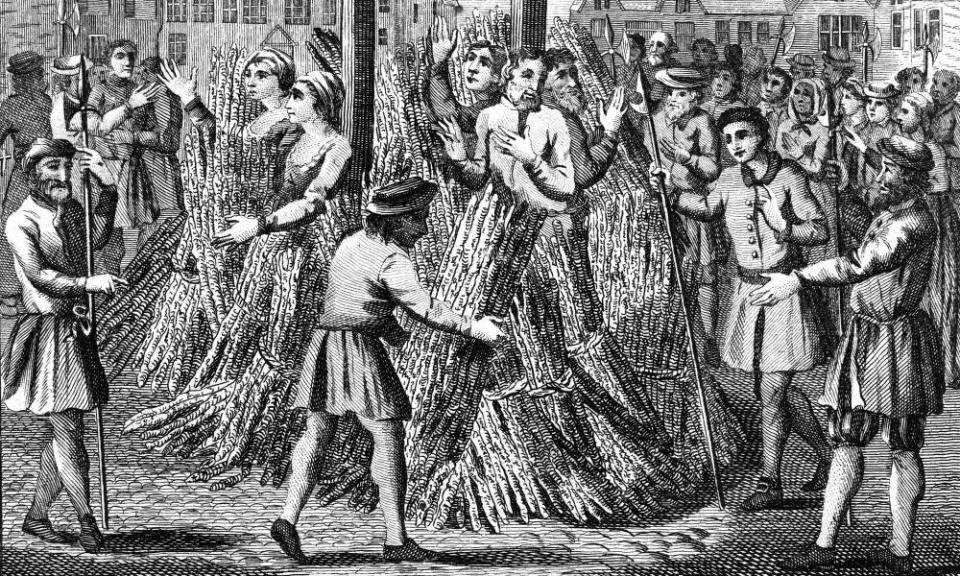

For Sandbrook, culture wars have always existed. They are what was fought as the Roman empire moved from paganism to Christianity in the early fourth century, and – just as today – that process involved clashes over statues and shrines.

Think about so much of 17th-century politics, when people would die over the wording of a prayer book

Dominic Sandbrook, historian

“What is certainly true,” he says, “is there are moments in history when disputes about history, identity, symbols, images and so on loom very large. Think about so much of 17th-century politics, for example, when people would die over the wording of a prayer book.” The same applies, he believes, to any number of periods, including the arrival of the permissive society in the 1960s, in which there is an attempt to establish new mores.

For Holland, the term culture war has a stricter meaning, relating to the German word Kulturkampf, which described the clash between Bismarck’s government and the Catholic church in 1870s Prussia. It is therefore specifically a dispute between religious and secular forces. Certainly if we look at America, where the modern incarnation of the culture wars was first identified, the conflicts over abortion and gay marriage have been fought, at least by one side, from an explicitly religious perspective.

The US sociologist James Davison Hunter gave popular currency to the term in his seminal 1991 book Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America. He argued that they were about the orthodox versus the progressive. That division remains visible in the UK, but without the religious component.

“I don’t think the Christian side of it matters,” says Sandbrook, disagreeing with Holland. “You can have culture wars in a non-Christian society.” Yet he agrees there might be a religious impulse at root.

“The Puritans took the culture wars with them,” he says. “Now America has re-exported the arguments back to us.”

He says that Holland thinks that “woke social justice warriors don’t realise they’re really 16th- and 17th-century Christian Puritans”.

If, as Holland believes, today’s social justice warriors are the unknowing heirs to Puritanism, then their preoccupations are less about morality than identity, even if dissenting opinions can still be denounced with a puritanical zeal. Nowhere is this tendency more evident than within the university system. The drive to “decolonise the curriculum” has led many academics to complain, usually off the record, of what one English professor described as a “dispiriting witch-hunt atmosphere” and professional intimidation.

As much of the intellectual motivation for challenging established power structures has emerged from the humanities, and in particular the field of critical theory, it is hardly surprising that this should also be the scene of some of the most conspicuous stands. In any war there are always innocent victims caught in the crossfire – and no doubt that’s how the 150 Oxford academics boycotting Oriel think of the students they are refusing to teach.

What’s notable is that the left initially saw issues of identity – those concerning race, gender and sexuality – as an area of straightforward progressive gain. The struggles were all about liberating oppressed minorities from under the yoke of white male power. But as the battles became both more complex and particular – what’s the correct position on whether self-identifying trans women with birth-male genitalia should have access to women’s lavatories? – so did rights begin to conflict and solidarity fray.

The divisions that have opened up within the Labour party are to an increasing extent grounded in differences in cultural politics between its middle-class metropolitan supporters and its traditional provincial working-class base. But there are also other tensions, for example between trans activists and gender-critical feminists. At almost the same time last week that Maya Forstater was winning her appeal against an employment tribunal, after saying that people cannot change their biological sex, the Labour leader Keir Starmer was reaffirming the party’s commitment to introducing self-identification for trans people.

The former leader Tony Blair has publicly advised Starmer to steer clear of these culture wars, because they are polarising areas that have limited voter appeal. But d’Ancona believes that’s an unrealistic ambition.

“A modern left-of-centre coalition has to include that social justice movement element … Starmer can’t just turn to BLM [Black Lives Matter] or #MeToo and say, away with you all.”

By contrast, there is a sense that each of No 10’s pronouncements on cultural or identity issues is calculated to maximise public support, even if it offends metropolitan sensibilities. As d’Ancona notes, this is why, in the run-up to a crucial G7 meeting, which is also President Joe Biden’s first foreign visit and the first time the international community of leaders has gathered in a long while, Boris Johnson was able to find time to admonish the England and Wales Cricket Board for suspending Robinson over his historical racist tweets.

And it’s probably a measure of how keenly No 10 studies the national mood that after the England manager, Gareth Southgate, wrote a stirring letter calling for support for his players, Johnson went from refusing to condemn England supporters for booing the team over taking the knee to appealing for the booing to stop.

It’s one thing to generate social media noise, and provoke a few high-minded columnists, but it’s hard to know if Johnson’s strategy has any deeper meaning or political capital. We’re in a new world of unpredictable directions and strange manifestations. “Look at Oliver Dowden,” says d’Ancona of the culture secretary, who used to be a centrist in David Cameron’s government. “He’s reborn as a kind of woke-buster.”

More troublingly, he argues, the politics of a culture war are febrile and unstable, with the potential to inspire fundamental bigotries leading to ever greater and more damaging divisions. These are not forces, he contends, that should be toyed with.

Yet if the culture war is leading to ever more entrenchment and acrimony, d’Ancona complains that “the standard Conservative response is, ‘We didn’t start it’. That’s not the response of true leadership. It’s the response of the playground.”

Whoever started it, the culture wars look set to continue for a while yet. With their preference for gesture over action, they don’t cost very much to participate in – if you discount hurt feelings – and require no great expertise or experience. Doubtless within them are worthy and perhaps essential debates, along with the familiar vices of name-calling, point-scoring and virtue-signalling.

The problem is that specific issues are seldom discussed on their merits, but packaged together into ideological job lots, the better to establish clear moral battle lines. The demarcation is not so much between left and right as right and wrong. If you accept one position, goes the thinking, it’s immoral not to adopt the rest.

The Nazi SS officer and playwright Hanns Johst once wrote a much misquoted line: “When I hear culture … I unlock my Browning.” In our thankfully less violent times, the mention of culture instead unloosens the tongue. The trick is to respect the principle of free speech, while maintaining the standards of civil discourse.

But the threat of Johst’s brand of righteous contempt is never far away. It would help if there were responsible figures cooling the debate. In the past, one person to whom you might look to perform that role would be the prime minister. In these culturally weaponised times he’s more likely to be flame-heating it.

Key flashpoints

The murder of George Floyd

Most aspects of the culture war are vividly symbolic rather than messily actual. But Floyd really was killed; the violence wasn’t silence but a police officer’s knee. The key thing, though, is that the murder was filmed and its documentation proved to be internationally inspirational, not least in the UK.

The Rhodes statue at Oriel College

The Rhodes Must Fall movement began over six years ago in South Africa. His statue in Oxford remains a provocative symbol of imperialism and, as its critics would say, white supremacy. This controversy is not going to go away anytime soon.

Winston Churchill’s statue in Parliament Square

The defacement of Churchill’s statue in last year’s Black Lives Matter protests was a galvanising moment. Whereas the toppling of slave-trader Edward Colston’s monument in Bristol was met with either support or complacency, the graffiti denouncing Churchill as a racist prompted a cultural backlash against BLM.

The Last Night of the Proms 2020

The most patriotic and indeed jingoistic of musical evenings, its traditional climax of Rule Britannia was played without singing, much to the annoyance of those who cried censorship. Online choirs were organised by way of cultural resistance.

The Keira Bell high court decision

In a judicial review brought by Keira Bell, the high court ruled that the Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust’s gender identity service (GIDS) for children with gender dysphoria had been misinterpreting the law on child consent in referring children as young as 10 for puberty blockers.

The court found the potentially serious long-term health consequences of taking puberty blockers are unknown, and that virtually all children at GIDS who started puberty blockers progressed to cross-sex hormones. The decision was condemned as “shocking” by Stonewall. The NHS has since suspended the use of puberty blockers for under-16s unless there is a “best interests” order from a court.

The European Union referendum

Although it was on the surface a political decision about where sovereignty resides, the issues surrounding Brexit were as often as not cultural at root. More than anything the referendum exposed faultlines in the nation that remain open and prey to exploitation.

The Oprah Winfrey interview with the Duke and Duchess of Sussex

It’s a mark of the weird political landscape that an American celebrity interview with a couple of fugitive royals could become the subject of so much hostility and polarised opinion. Prejudices and preferences concerning race, class and nationality created a meta-narrative that successfully overshadowed the banality of the conversation.

Laurence Fox’s appearance on Question Time

When Fox rejected the notion that Meghan Markle was a victim of racism, he announced himself as a cultural, “anti-woke” warrior ready to defend white males against the “racism” of being described as “privileged”. Just over a year later he was running to be mayor of London. He lost.

Oliver Dowden’s warning to cultural institutions

A policy of non-interventionism has long been the accepted relationship between culture secretaries and cultural institutions but Dowden appeared to breach this understanding when he told museum and gallery heads that they should “retain and explain” contentious statues, and not be drawn into “rewriting history”. Because history is fixed and symbols are for ever.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies