Erie man discovers early Underground Railroad station and once-enslaved couple who ran it

The site of a previously unknown Underground Railroad station in Erie will be commemorated by a new state historical marker, thanks to a retired Erie engineer.

The Erie station was operated by freed Black woman Emma Howell and husband James Ford, who twice escaped slavery, at their East 12th and Parade Street home two centuries ago. Their story was uncovered by Kevin Johnson, who saw a mention of the station in a footnote.

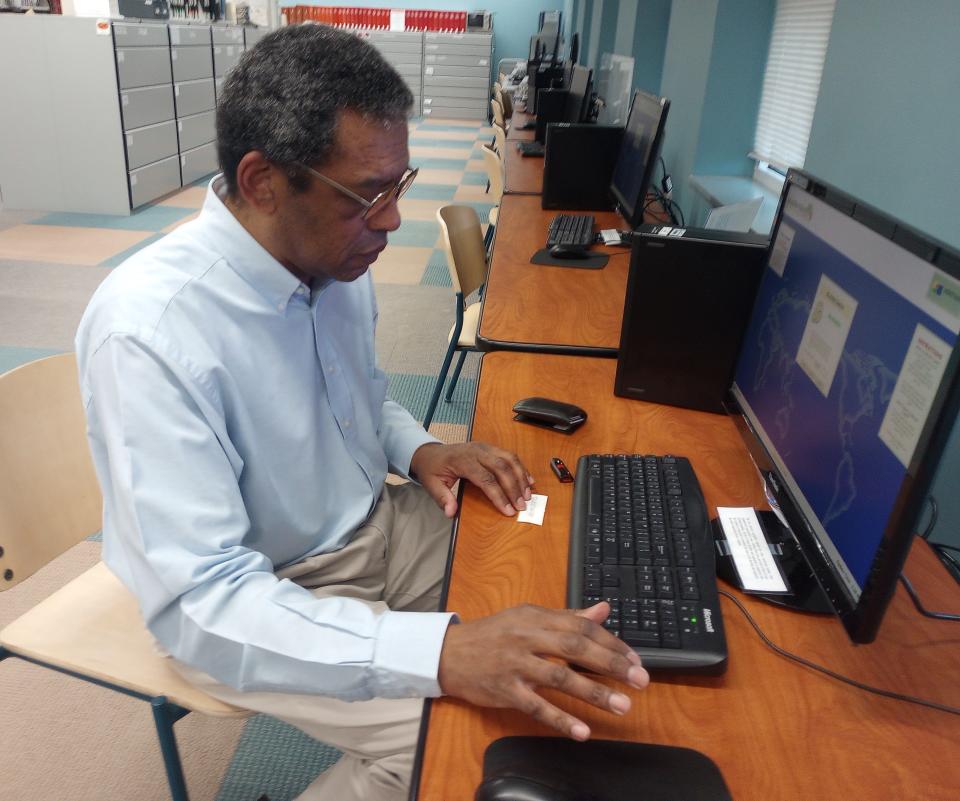

"I don't claim to be an historian," said Johnson, 61, who has a degree in math from Ohio State University and a master's degree in engineering from Gannon University. He worked as a mechanical engineer at GE Transportation in Erie and at Navistar in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and returned to Erie in 2011. He researched Ford Station with help from his wife and a few friends.

"We just accumulated this information and wanted to get it out and fill in some holes in early Erie history," Johnson said.

Connecting the dots to forgotten history

The Underground Railroad was a network of activists who sheltered escaped slaves from the South and guided them to freedom, mainly in Canada, from the late 1700s through the Civil War.

Johnson was reading a book on the Underground Railroad when he saw the footnote about a woman whose parents had conducted escapees to freedom from an Erie station. It sparked a years-long search to uncover and verify the story.

"I'd always heard that Erie was a major hub for the Underground Railroad, and so every once in a while I'd look at books on the Underground Railroad to see if I could find any information on Erie's involvement," Johnson said. "But I was never able to, until one day in 2011, I saw a footnote in a book by Wilbur Siebert about a woman who said her parents had operated an Erie station."

The footnote in Siebert's "The Underground Railroad From Slavery to Freedom: A Comprehensive History" referenced 1863 testimony to the American Freedmen's Inquiry Commission by Amy Martin, who said that her father's name was James Ford. "When we were in Erie, we moved a little way out of the village, and our house was ... a station of the U.G.R.R.," Martin said.

Johnson began a meticulous search of property records, early Erie newspapers, the National Archives, Erie County Historical Society archives, Blasco Library Heritage Room collections and other records to piece the story together.

"It was about connecting the dots I had to work with and answering each question that arose," Johnson said. "The first dot was that footnote. The next was, was there a Black man in Erie named James Ford?"

Johnson kept connecting the dots and last year applied for a Pennsylvania Historical Marker for the site. The Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission approved the application in December.

Emma Howell and James Ford

Emma Howell, her mother and sister came to Erie with their enslaver, John Grubb, in 1795. Grubb was part of a team authorized by the state to survey newly-acquired land in what today is Erie County. Slavery was then still legal in Pennsylvania although a 1780 state law required its gradual abolition.

In 1800, Howell gave birth to William Bladen, the son of Boe Bladen, an enslaved man working with the survey team. William Bladen is believed to be the first Black person born in Erie.

Howell was sold in 1803 to William Wallace, lawyer for the Pennsylvania Population Land Company, which sold the tracts of land laid out by the survey team. Wallace bought more than 15,000 acres of property throughout Erie County. He gave 45 acres in Erie and what was then Millcreek Township to Howell when he freed her in 1811.

"Emma Howell owned property from Ninth Street to 15th street on the east side of Parade Street, and from Ninth Street to 12th Street on the west side of Parade," Johnson said. "At that time, the land on the east side of Parade Street was in Millcreek Township.

"Emma Howell was the first Black woman to own land in Erie and in Millcreek."

"Black Emmy," as she was known, according to an 1874 Erie Gazette column remembering Erie's early days, also is believed to have been the matriarch of Erie's first Black family and the first Black person to address what then was Erie Borough Council, in 1822, when she successfully lobbied for repairs to a bridge near her home.

James Ford escaped from slavery but was captured by Native Americans during Anthony Wayne's 1794 campaign against the tribes. He was sold to a British Indian agent in Canada, escaped again and made his way to Erie, according to Ford's 1838 obituary in an abolitionist newspaper.

Ford and Howell married, built a log home on 10th Street and later built a home at East 12th and Parade streets.

"It was a boarding house for African-Americans and also served as the first tavern for African-Americans in Erie," Johnson said. "It was a place where Black people in the city could safely congregate.

"And the Underground Railroad station was there, and on Howell's whole 45 acres, from 1811 to 1836."

The routes to Canada from Ford Station

Emma Howell's land provided easy access to Lake Erie.

"From an 1816 map of Erie, the first route would be to go down Four Mile Creek to its mouth, where Erie's first dock was located, and leave from there," Johnson said.

When Emma Howell and James Ford's daughter, Amy, then 16 or 17, left for Canada with escapee John Martin in the late 1820s, she's believed to have taken a different route, overland to Niagara Falls.

"If they'd crossed the lake, they probably would have landed in Long Point and then could have settled in St. Thomas, London, Brantford, Hamilton, or any number of towns that were very acceptable to runaway slaves," Johnson said. "But if they went up the coast they would be in St. Catharines, where they settled, before they got to any of those towns."

Amy Ford married John Martin. Her parents "in their old age" sold their Erie property and went to live with her in St. Catharines.

Probable Ford Station ties to John Brown

Runaway slaves may have been guided to Ford Station along the Underground Railroad route from Crawford County operated by abolitionist John Brown, who had a tannery near present-day Guys Mills from 1825 to 1835. Brown's cousin, Miles Barnette of Waterford, also was a conductor on the line.

'The Great Migration': Erie pastors shepherded Black families from Laurel, Mississippi, to Erie

"If these runaways are coming from (Crawford County) to Waterford and presumably to Erie, Ford Station was the only Underground Railroad Station known to have been operating here before 1841," Johnson said.

Another indication that Ford Station may have been a stop along Brown's network is that a farmer working with Brown once asked for another wagon to accommodate seven or eight more fugitives than he could handle.

"If you can't handle seven or eight more people, how big was this group they're conducting and where would you put 14 or 15 or more runaways in Erie without them being seen?" Johnson said. "Besides Emma Howell's farm, there were only individual homes and buildings in Erie at that time. You could try to hide one person here and another there, but the Ford home and boarding house and its 45 acres on the outskirts of town seem to be the logical place for them to go."

And according to Amy Ford Martin's 1863 testimony, "The fugitives would be told to come to our house ... they used to hear of our place long before they got there."

Brown led the aborted raid on the U.S. arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in October 1859 in hopes of providing weapons for a slave insurrection in the South. He was captured, tried and executed.

Ford family ties to Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass

Harriet Tubman, an escapee known as "Moses" for repeatedly returning to the South to lead others to freedom, lived in the Black community in St. Catharines, Ontario, from 1851 until 1859. The small community was comprised of the formerly enslaved and their families, including John and Amy Martin and, after 1836, Emma Howell and James Ford.

Still linked today: Black communities in Erie and Laurel, Mississippi

"It was Harriet Tubman who recommended people in St. Catharines for Dr. Samuel Howe to interview," Johnson said, for the 1863 American Freedmen's Inquiry Commission. "And one of those people was Amy Martin."

It was her testimony that was mentioned in the footnote that sparked Johnson's search for information on her parents' Underground Railroad station in Erie.

Amy Martin for a time worked as a cook in the Rochester, New York, home of the wealthy George Mumford family.

"This family had other homes in San Francisco and Paris and could have hired anyone they wanted to be their cook. So why a poor Black woman who lived in another country?" Johnson asked.

According to Johnson's research, it might have been because of Mumford's neighbor, Frederick Douglass.

"Douglass had moved to Rochester in 1848 and was the town's version of a rock star. Everyone knew him, and he had visited St. Catharines a number of times," Johnson said.

Another servant in the Mumford home was related to Douglass by marriage.

"So Amy Martin lived next door to Frederick Douglass and worked with someone related to him. And there are other indications that she knew him," Johnson said.

Douglass escaped slavery and was among the nation's leading abolitionists before and during the Civil War.

A work still in progress

Kevin Johnson first planned to share his Ford Station research in a display at Blasco Library.

But each new discovery led to more questions and more research to answer them.

"It got to the point where a display would have to be huge to answer all these questions," he said.

Johnson instead wrote a book, "The Short Story, Big Life of Emma Howell, the Ford Family, and Erie's First Underground Railroad Station." Johnson self-published four copies of the book, including one available to the public in the Heritage Room of Blasco Library.

"It wasn't done for economic gain but to get this information out and fill in some holes in early Erie history," Johnson said. "This isn't really Black history. It's Erie history. These people came to Erie as early as anyone else did."

And the city's early Black community was not isolated from its neighbors. James Ford and other family members were listed with their white neighbors as witnesses to an 1812 marriage performed by John Grubb, Emma Howell's former enslaver and Erie's first justice of the peace. The marriage certificate was written and preserved in a school workbook that belonged to one of Grubb's daughters.

"This document shows that they were treated as people and acknowledged as people. For me, it's the most important document in Erie, hands down," Johnson said.

Johnson hopes that others will be able to add to his research on early Underground Railroad operations in Erie. He also hopes to create a documentary as a kind of prequel to the "Safe Harbor" documentary about the Underground Railroad in Erie after Ford Station.

In the meantime, the Pennsylvania Historical Marker will commemorate Ford Station. A dedication date has not been set.

YourErie.com first reported on Johnson's research for the new marker.

Contact Valerie Myers at vmyers@timesnews.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Erie man discovers city's earliest known Underground Railroad station

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies