Elusive back-to-back grand slams remain rugby union’s holy grail

The England side of 1992 are one of just two men’s teams in the past 98 years to complete a double grand slam triumph

Whenever the Six Nations looms out of the wintry murk it is important to give a respectful nod to the gladiators of yesteryear. On Sunday, as it happens, one of the unsung heroes of English rugby also celebrated his 80th birthday in deepest Dorset, a suitable milestone for a man who coached his country to a grand slam in 1980, their first championship clean sweep since 1957.

Mike Davis has been battling Parkinson’s of late but can still occasionally be found practising a few wedge shots on the playing fields adjoining his home in Sherborne. Even in his coaching pomp – he also won 16 caps as an England lock forward – it was never about him, whether he was teaching clumsy kids like us the rudiments of basketball, or tutoring the country’s best rugby players. Only the snug purple tracksuit bearing a red rose offered a clue to his ‘other’ sporting life.

Related: Keith Earls: ‘Hank started to take over. I got to a stage where I hated rugby’

That all-conquering 1980 side, captained by Bill Beaumont, was deservedly feted – not least for allowing England to escape with some dignity from the 1970s when, at one point, they collected three wooden spoons in a row. Once again, though, the curtain was to fall with a dull thud. By the start of the 1990s, the 1980 triumph under Davis’s unselfish guidance was still only the second grand slam England had managed since 1928.

Which is why, 30 years on, it feels equally appropriate to remember the other great England side of the late 20th century who completed back-to-back grand slams in 1991 and 1992. In between they managed to lose a World Cup final but, in some respects, that adds a further dimension to their achievement. To place it into context, only one other men’s side in the past 98 years – France (1997 and 1998) – have captured the northern hemisphere holy grail twice in succession.

The double grand slam remains a remarkable feat – even the greatest Welsh sides of the seventies never managed it. And not only did England re-enter the winners’ circle in 1992, they did so convincingly. Under Will Carling and Geoff Cooke, they established a new record for most tries scored in the Five Nations (15) and conceded just four, having kicked things off by beating Scotland 25-7 at Murrayfield in their opening match.

Three decades later – and with Scotland awaiting Eddie Jones’s England on Saturday week – it is that game, rather than the explosive fixture at the Parc des Princes (of which more later) that Simon Halliday chooses as his most satisfying. Part of it was down to his own display – “I had one of those games when everything seemed to go my way” – and partly it was the psychological baggage finally jettisoned. “In 1986 we were thumped by 30 points at Murrayfield, 1988 was a kicking match on and off the field, then there was the grand slam that never was for us in 1990. I had real history with that venue.”

Ireland were subsequently thumped 38-9 – Halliday recalls it as “one of the best Twickenham performances I can remember being part of” – and a fortnight later England set out for Paris. On paper they had every physical base covered – a pack consisting of Dean Richards, Peter Winterbottom, Mick Skinner, Wade Dooley, Martin Bayfield, Jeff Probyn, Brian Moore and Jason Leonard was always going to be forthright. Outside the half-back pairing of Dewi Morris and Rob Andrew also lurked more top operators with loads of big-match experience: Carling, Jeremy Guscott, Rory Underwood, the in-form Jonathan Webb and Halliday on the right wing.

As Richards has subsequently recalled in the splendid, recently re-published paperback edition of Behind the Rose, staying cool and gently riling the French was a big part of the plan. “The policy was that if they hit you, you smiled and then gave them a wink to wind them up even more.” Moore had already irritated his hosts by publicly predicting “a boxing match” before kick-off.

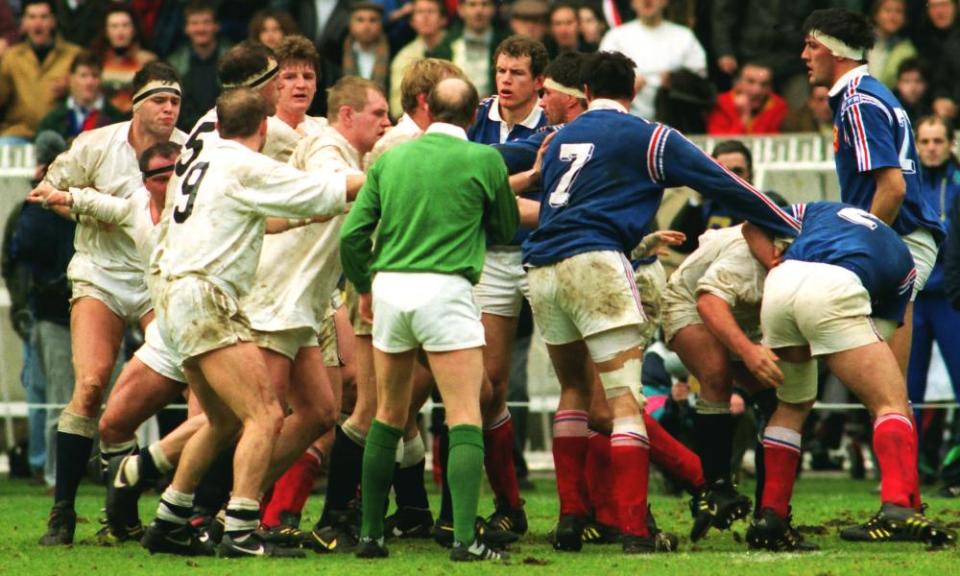

Sure enough, it all kicked off in earnest in the second half when two of France’s front-row, Grégoire Lascubé and Vincent Moscato, were sent off for stamping and a head-butt, respectively. The home crowd went similarly wild, causing the Irish referee Stephen Hilditch to be given a police escort off the field at the end. Halliday was as grateful as anyone to the Irish official following an incident five minutes after Moscato’s departure. “I slightly involuntarily body-checked their left winger and that entire side of the Parc des Princes tried to get me sent off. I remember saying to Hilditch: ‘I haven’t head-butted anyone, I haven’t stamped on anyone’s head, you can’t send me off for that.’”

Once the dust had finally settled, though, England had scored four tries in Paris for the first time since the war and won 31-13. The final act, by comparison, was relatively comfortable. Wales were beaten 24-0 at Twickenham, with Carling scoring a try in the opening minute, after which Halliday reverted to his day job as a stockbroker. Carling has since said that his England side “were at the height of their powers” and history would appear to bear him out.

Will anyone repeat the feat in this increasingly chien-eat-dog professional era? Maybe one day but England, warns Halliday, would currently be better off focusing on more immediate priorities. “This English team are going to have to play out of their socks to beat Scotland on Saturday week. Don’t listen to the people who say ‘It’s just another day at the office’. I think Scotland have a team that shouldn’t fear anyone.” As Davis, Halliday and every other old warrior can testify, the warm glow of past victories does not indefinitely protect against the chill blast of modern-day reality.

• This is an extract from the Guardian’s weekly rugby union email, The Breakdown. To subscribe, just visit this page and follow the instructions.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies